Rachel McBride Lindsey

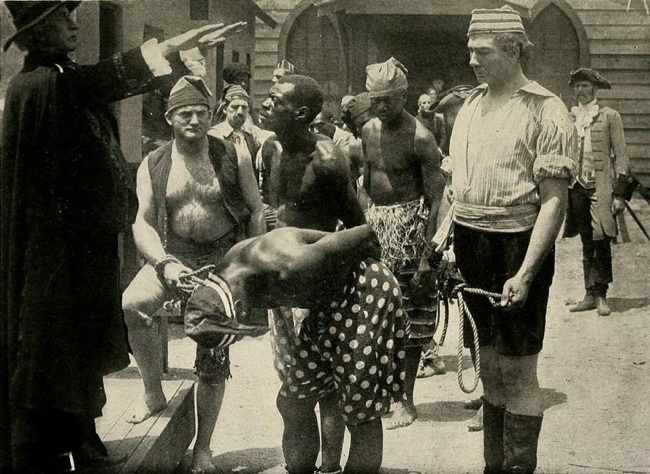

It is broadly known that David Wark Griffith’s 1915 cinematic tinderbox Birth of a Nation sits at a juncture of literature, theater, and cinematography. Based on and deriving much of its narrative structure from Thomas Dixon’s 1905 novel The Clansman, the story was subsequently adapted for the stage before Griffith interpreted it yet again for the still nascent film industry and developing movie culture. Less often discussed is how, in addition to the film’s influence from literature and theater, in 1915 American cinema was still in the process of defining itself apart from the visual conventions and narrative possibilities of still photography. Through plot device, camera technique, and historical conceit, Griffith’s epic story of the triumph of racially defined and providentially guided national unity out of racially contrived sectional chaos leans heavily on the early history of American photography.

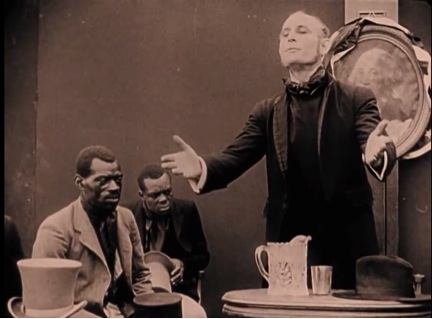

Histories of and reflections upon Birth of a Nation often struggle with how to remember this film, and tend to center on the craftsmanship of its production and the beguilement of the narrative. As NPR’s Code Switch put it in 2015, Birth of a Nation was an “epic film, embedded bigotry” whose “artistic ambition” was affected through “three hours of racist propaganda.” Attending to “heart interest,” “drama,” “danger,” “comedy,” and “rescue” had been part of Griffith’s filmic strategy since his directorial debut in The Adventures of Dollie in 1908, and Birth of a Nation orchestrates these elements into an invective of national becoming. Like P.T. Barnum half a century before, Griffith was a master showman who knew how to throw a little drapery on the facts without showing his hand in the trick. As such Griffith was not only a gifted technician. He was a master of presentation. The most explicit example of his painstaking attention to the experience of this film is Birth’s official score, timed to complement and reinforce the visual experience with emotionally appropriate music. But, he also insisted that audiences not be allowed to enter the theater after the film started, that there was an etiquette of spectatorship, or rather of visual experience, that films like his commanded. Recognizing Griffith’s orchestration of audiences’ experience of his film, his attempt to standardize its reception from Los Angeles and New York to St. Louis and Atlanta, asks us to consider not only the production of the film and Griffith’s narrative intent, but also, revealing, the politics, practices, and pieties of beholding that audiences brought to the theater.

At the center of the visual regime of providential American ascendancy in these early years of the twentieth century was the camera. “The camera” is of course a universalizing abstraction, suggesting that specific contraptions and uses—from motion picture studio apparatus to professional large format cameras to increasingly popular hand cameras—are somehow inseparable from the visual habits and technological priorities of a white male gaze smuggled into memory as the history of “the medium” or, just as troubling, “the film.” Still, the press and public described Birth of a Nation, along with other films between 1910 and 1920, as a “photoplay,” and when the film opened at the Liberty Theater in New York in March 1915, the papers gushed that “narrative photography took a long stride forward.” Moviegoers saw Birth of a Nation within a visual web, a hall of mirrors that exceeded any single film or image, and that spanned and connected religion, race, and nation in moments of beholding. Shifting attention from the camera to beholding is instructive as we consider the movie’s legacy over its first one hundred years.

The visual confluence of religion, race, and nation was informing practices of photographic beholding long before Griffith and his cameraman, Billy Bitzer, began filming “The Clansman” in 1914 (Griffith did not change the name of his film to Birth of a Nation until immediately prior to its theatrical release). In the movie, Griffith and Bitzer draw on these habits through plot devices, camera techniques, and the historical conceit of the camera itself. The most explicit diegetic use of photography is as a plot device to advance the fated romance between Elsie Stoneman, daughter of the northern Senator who enables the “mulatto” Silas Lynch in his quest for power during Reconstruction, and Ben Cameron, the protagonist who ultimately saves the day by unifying the “former enemies North and South … in common defense of their Aryan birthright.” In the earliest frames of the film, Elsie’s brother gives Ben a small, ninth-plate ambrotype of Elsie.

An intertitle tells us that Ben finds “the ideal of his dreams in the picture of Elsie Stoneman… whom he has never seen.” During the war, Ben retreats to his tent to read a letter from home and, when sticking the letter back into his breast pocket, again finds the picture of Elsie, whom he has still yet to meet and perhaps never will. The providential or at least serendipitous meeting of Ben Cameron and Elsie Stoneman occurs in a Union hospital, where Elsie is a nurse and Ben is convalescing after being wounded and captured. In a made for telenovela moment, Elsie happens upon Ben and he tells her that, “Though we had never met, I have carried you about with me for a long, long time.” This use of the studio portrait as a connection that spans time and space, and his statement that “I have carried you about with me”—not a likeness of you, or a picture of you, but YOU—is in keeping with nineteenth and early twentieth century practices of photographic beholding. It is also one of the first instances when a photograph is used as a cinematic plot device, inaugurating a convention that became an industry staple. But Elsie’s is not the only pictorial plot device. Griffith also deliberately places portraits of George Washington in the first act of the film to tie vignettes together, a subtle visual cue to the new dispensation of the American people who began with the ascendancy of national unity in the wake of sectional strife.

Abolitionism, the assassination of Lincoln, and Reconstruction were born of the age of Washington and the Republic; an order that the birth of the nation replaced. Indeed, when Lincoln is shot at Ford’s Theater, his blood covers the portrait of Washington on the front of the theater box. This birth was a baptism in blood. Released in Los Angeles just months before the fiftieth anniversary of the peace at Appomattox, the Birth of a Nation came on the heels of more than three years of commemorating the Civil War that catalyzed this new era of the American people. Washington’s portrait underscored the tectonic shift in American national imagination while Elsie’s likeness underscored the human, and indeed providential, connections between North and South that Griffith saw at work within the grand narrative.

Even more central to Birth of a Nation than direct uses of photographs were the photographic sensibilities that imbued the film with historical authority. Griffith’s preemptive “Plea for the Art of the Motion Picture” associates the work audiences are about to see with “the bright side of virtue” that is “illuminated” in recognized moral authorities such as the Bible and Shakespeare. Griffith’s brief prophylactic against the threat of censorship would later be expanded into a sixty-nine page treatise on The Rise and Fall of Free Speech in America.

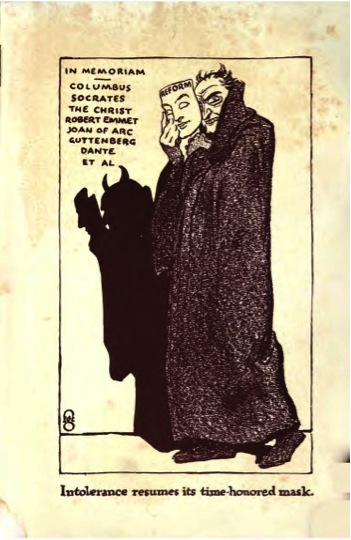

The frontispiece to this 1916 pamphlet graphically anticipates Griffith’s diatribe against devilish and war-provoking “intolerance” in the guise of moral reform. The motion picture, he contends, is uniquely positioned as “war’s greatest antidote.” This was a message he deliberately staged in Birth of a Nation. “We believe we have as much a right to present the facts of history as we see them, on the motion picture screen, as a… Bancroft… or a Woodrow Wilson has to write these facts in his history.” Even as Griffith draws on Woodrow Wilson’s History of the American People in his construction of “historical facsimiles” of events, which are essentially tableaux based on descriptions from Wilson and other texts—this one of President Lincoln signing an order for 75,000 troops comes around 25 minutes into the film and is attributed to an early Lincoln biography—he is also pivoting away from texts to what he described as the more accessible history provided by the “laboring man’s university,” motion pictures. Birth of a Nation was no retelling of American history. It was, for Griffith, a more truthful telling than had ever before been possible. This claim, that the camera was the most reliable vehicle of history, was as old as the daguerreotype, the first popular photographic technique in the United States in the early 1840s. But it had renewed significance in the decades leading up to 1915 as champions of American civilization (and military prowess) relied on photographs of war and indigenous peoples around the globe to bolster public support of interventionist policies and American cultural expansion.