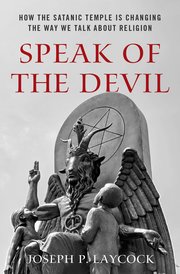

In our interview series, “Seven Questions,” we ask some very smart people about what inspires them and how their latest work enhances our understanding of the sacred in cultural life. For this segment, we solicited responses from Joseph P. Laycock, author of Speak of the Devil: How the Satanic Temple is Changing the Way We Talk about Religion (Oxford University Press, 2020).

1) What sparked the idea for writing this book?

I have covered The Satanic Temple for Religion Dispatches since 2013. In the beginning I remember feeling stunned that this group was actually doing things that had long been hypothetical scenarios in debates about the establishment clause. As a former high school teacher, I often heard the argument, “But what if Satanists wanted to hold prayers at the school? Would you be OK with that?” But, of course, there were no Satanists––so the person who wanted to evangelize the school children was free to give whatever answer was convenient. But now the Satanists are here and we all have to put our money where our mouths are. So The Satanic Temple’s provocations have created an opportunity to see what people really think about religious freedom when they are forced to be honest. Significantly, this is the role of Satan in the Book of Job: the adversary who tests how strong our professed convictions really are.

2) How would you define religion in relation to your work? Where do you see the sacred or sacred things in this book?

This book definitely aligns with more recent scholars who suggest “religion” is not only a second-order category, but a term that is useful for a variety of political interests precisely because its meaning is vague and even protean. It has been interesting to see the various arguments formulated by The Satanic Temple’s opponents that this is not a real religion, but rather “trolling,” “a political view,” or even “an anti-religion.” All of these arguments operate on an unstated assumption that “religion” is inherently distinct from trolling, politics, or opposition to other religions. Interestingly, these arguments have persisted even after the IRS granted The Satanic Temple tax-exempt status as a church.

I also find The Satanic Temple interesting because they are actively trying to persuade the public that “religion” is not synonymous with the belief in supernatural beings. Of course, religious studies scholars and the Supreme Court have recognized this for decades. But the public often assumes that if The Satanic Temple does not pray to a literal fallen angel they cannot be a real religion. In arguing why they are a real religion, The Satanic Temple proposes a more functional definition of religion: they point out that they have fellowship with one another and their community is united by a shared set of stories, symbols, and rituals. In my book I propose Catherine Albanese’s polythetic definition of religion as creed, community, code, and cultus as a better model for thinking about how The Satanic Temple is “religious.”

But this is not to say there is nothing transcendent about The Satanic Temple’s beliefs. Malcolm Jarry, the co-founder who drafted many of the group’s seven tenets, expressed that “justice” is a transcendent idea: we can move closer toward justice but never fully attain it. He also suggested that the pursuit of justice leads ultimately to the destruction of the ego. I see this as further evidence that The Satanic Temple is not reducible to set of political views.

3) Can you summarize the three key points you’d like the reader to walk away with when finished?

First, The Satanic Temple do not worship evil or hate Christians. A lot of people––including colleagues who ought to know better––assumed that because I was researching this book I was either in terrible danger or morally defective. None of the Satanists ever took issue with my religious affiliation, but I did not always see that same degree of tolerance reciprocated from non-Satanists.

Second, The Satanic Temple is not an elaborate hoax. This was a reasonable interpretation in 2013 when The Satanic Temple consisted of only a handful of people doing political stunts that involved humor. But in 2020 when The Satanic Temple has chapters all over the country and hundreds of members who meet regularly to perform rituals, discuss books, and do charity work, claiming it’s all a hoax seems more like willed ignorance.

Third and most importantly, The Satanic Temple is worth paying attention to. Their lawsuits and other provocations are forcing a public conversation about what “religion” is, what “religious freedom” means, and what religious pluralism looks like. Beyond that, I see The Satanic Temple as part of conversation about what kind of country America is and ought to be. “Satan”––imagined as either the enemy or a role-model––is really a way of talking about who really belongs and who does not; who is just and who is tyrannical. It is not a coincidence that an unprecedented number of people decided to publically identify as Satanists at the same time that Trump received a greater percentage of the white evangelical vote than any previous president.

4) Who were intellectual models or inspirations for you as you wrote this book?

There were many. I had a lot of conversations with my father, Douglas Laycock, about the Satanic Temple. I remember him shaking his head a lot when I tried to explain this group, but he helped me think through some of the Constitutional issues at stake. Stephen Prothero’s ideas about culture war and the problem of “pretend pluralism” were also an important influence. The chapter on pluralism draws on both Diana Eck, whom I studied under briefly, and Russell McCutcheon. Although these two are often presented as foils on this issue, I found both their ideas useful. Lastly, this book would have been impossible without the work of religion scholars such as Jesper Aagard Petersen, Per Faxneld, James R. Lewis, and Massimo Introvigne, who study religious Satanism.

5) What was the most difficult thing about writing the book? Did you encounter any unexpected problems or challenges?

When I observed the religious liberty rally in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 2018, I was genuinely worried that violence would ensue between the Knights of the KKK, Neo-Nazi groups, and Antifa activists, all of whom attended. I will not get into specifics, but suffice it to say that I have been doing ethnography with marginalized religious groups for over a decade and this was the only time I have been concerned about safety.

That same summer, the group experienced a so-called “civil war” and broke up into numerous smaller Satanic groups. This was a bitter experience for everyone involved and it was also depressing for me as a researcher. People I had already interviewed suddenly wanted second interviews now that they were no longer affiliated with The Satanic Temple and could tell me what “they really thought.” Sociologically speaking, this schism was inevitable. What we are seeing is not just a new Satanic group but the emergence of an entire milieu of progressive, politically engaged Satanic groups. In seems as though the community has largely recovered and moved on from the rancor of 2018. At least I hope so.

6) What’s the most unexpected response, critical or positive, that you’ve gotten about the book?

We held a book release party where a Satanist gave the horns and yelled, “Hail Joe!” at me. Having received blessings and prayers from a wide variety of religious traditions, that was sort of a neat thing to have on my bucket list.

7) With this book done, what’s up next for you?

My next project is an anthology called The Penguin Book of Exorcisms that should be out by Halloween 2020. This will contain accounts of exorcisms from around the world and throughout history. It will include things like diaries, court testimony, scientific reports, and church documents, some of which of which have never been published before. I teach a course on exorcism at Texas State and have written several articles on the topic. To me, exorcism presents a serious challenge to how we go about “doing” religious studies. It is regarded as an “extraordinary” religious practice even though spirit possession occurs in nearly all cultures and “deliverance ministry” is now an established part of the American religious landscape. As religion scholars, it seems we can neither accept claims of spirit possession at face value nor dismiss the whole phenomenon through medical materialism. So what do we do? I think Robert Orsi’s idea of the “tradition of the more” is a good start. But as historians we also need better data about what about is actually being described. At any rate, I hope readers will find this material as interesting as I do.

Joseph P. Laycock is an assistant professor of religious studies at Texas State University in San Marcos, Texas. His research agenda includes American religious history, new religious movements, and moral panics. Recent books include Dangerous Games: What the Moral Panic over Dungeons and Dragons Says About Religion, Play, and Imagined Words (University of California Press, 2014) and Speak of the Devil: How the Satanic Temple is Changing the Way We Talk About Religion (Oxford University Press, 2020).