Louis A. Ruprecht Jr.

There is more than one way to look at religion, and more than one place in which to find sacred energies alive and well today. These are neither surprising nor controversial contentions for readers of Sacred Matters. The central idea here is that the traditional notion of modern “secularization” does not capture the realities of the ever-shifting religious landscape in the contemporary United States (and in much of the modern world, for that matter). It is not that religion goes away, nor that religion is increasingly marginal to a world whose “secular” institutions are determined to keep religion out. Rather, the story of the modern is the story of religion’s gradual dispersion into other places, and other institutions.

Religion does not go away; it goes elsewhere.

Viewed this way, modern institutions are not just secular; they are also bearers of and placeholders for the sacred. In this essay, I want to turn to the place of Art in this shape-shifting way of viewing religion, modern institutions and the perennial appeal of the sacred.

My point of entry, however, may be an unexpected one: it is, of all places, the Vatican. For there is more than one Vatican—these days, at any rate—and more than one (catholic) church, and whereas some of these versions can seem decidedly un-modern and illiberal, others are far more progressive and forward-looking. Establishing some lines of connection between them is the challenge and the virtue of those who work in this field of enquiry.

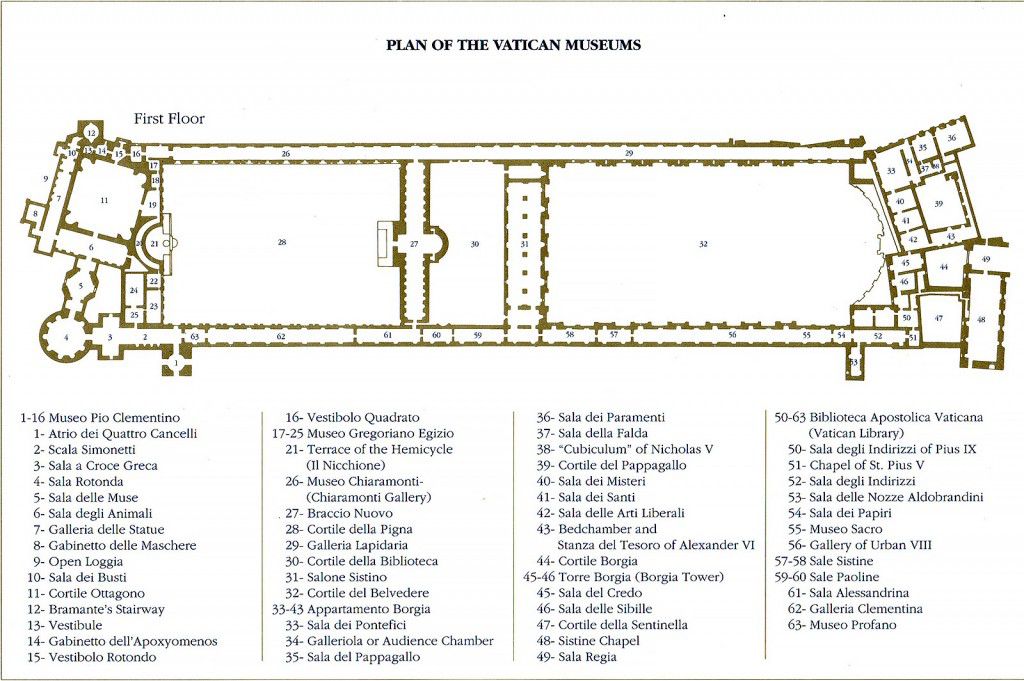

The Vatican today houses a public museum (largely pagan), a private library (uncommonly cosmopolitan, progressive, and most recently, digital), a secretive bank (which Pope Francis I has just committed to a dramatic “new opening”), as well as a residential palace and the monumental Basilica of St. Peter. Establishing connections between this complex array of institutions is not at all easy; in this essay I shall focus on the library and the museum.

The library and museum used to be a single institution, back when the Apostolic Palace at the Vatican housed a library with a large and impressive collection of paleo-Christian and pagan religious artifacts, as well as an uncanny collection of Egyptian papyri, ancient codices and more modern print books. But gradually, with time, these collections were destined to be separated—the church, the palace, the library, and the museum—and a modern classical art museum gradually went public for the very first time.

In 1757, a “Sacred Museum” housing impressive finds from Roman catacombs and the like was opened to a select viewing public inside of the Apostolic Palace at the Vatican. This came by order of Pope Benedict XIV (Prospero Lambertini of Bologna). Just one decade later, in 1767, that same palace was bookended by yet another museum, the “Profane Museum” this time, located on the northern end of the main Library corridor. And all the rest followed.

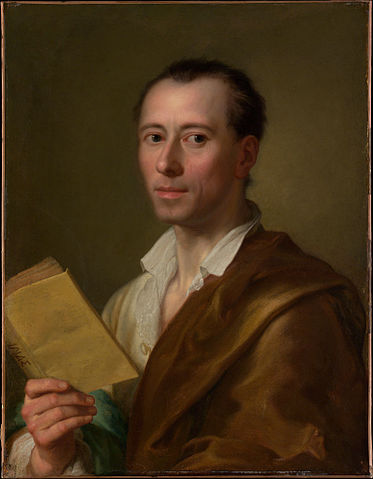

Pope Clement XIII (Carlo Rezzonico of Venice) presided over what became a rather seismic reorganization of the Vatican Library. But there were two others who bore primary responsibility for the creation of this surprising museum with the surprisingly profane name: Alessandro Albani (1692-1779), the Cardinal Librarian of the Vatican, nephew to the predecessor-Pope Clement XI, and the most renowned collector of classical Greek and Roman art in all of Europe; and Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768), one of the most famous converts the Catholic church attracted in the revolutionary course of the eighteenth century, as well as the so-called father of the modern canons of Art History, Archaeology, and Neoclassicism.

What Albani and Winckelmann initiated has not come to rest in our own times. In fact, we live entirely within the “museum culture” they first envisioned and promoted.

Whether unwittingly or not, Winckelmann’s Vatican career resulted in the “great detachments” that I now see as essential to modern thought and modern religion alike, as he oversaw what Pope Clement XIII referred to as “the complete separation” of sacred and profane materials at the Vatican Library. In one swift and shattering decade, the Profane was detached from the Sacred, visual material was detached from textual material, statues and paintings were detached from books, such that public museums were detached from private libraries… and, as a result, modern Art was detached from modern Religion as well.

By viewing Greek religious images as Fine Art, Winckelmann’s greatest intellectual innovation, it was easier to justify placing them on ecstatic public display. Thus “the profane” was to be domesticated in an entirely new, and entirely public, space in which all free citizens might freely view it with a casual ease that is quite surprising by the standards of the day. It had not been so very long before that such “pagan idols” had been condemned, where they were not actually destroyed, by iconoclastic Christians.

When the Dutch Pope, Adrian VI, was give his first tour of the Vatican sculpture garden in early 1522 by his host of proud cardinals, he was shocked. “Nothing but pagan idols,” he is reported to have said (in ecclesiastical Latin), and threatened to sell off the entire collection. He died within a year.

No longer. Now, the violent policing of the Church was aimed at suspect books, not suspect images. Clearly, something changed rather decisively in the religious mentality of the day.

Sarcophagus relief. Pio Clementino Museum; Octagonal Court. Vatican Museums. Photo by Flickr user “Colin,” April 11, 2012. Available via Flickr.

At the far end of these subtle and often quite supple institutional developments, art was destined to serve an important role in the new spirituality, speaking to the same institutional displacements, and the same spiritual discontents as Saint Francis’ spirituality had done half a millennium before. Artists do what saints once did: grant us epiphanies. Posing the modern question of the place and purpose of art, and of modern art museums more generally, is thus subtly to pose a deeply religious question about the varying locations of sacrality.

The thing was called a mouseion, echoing an ancient Greek word meaning “shrine to the Muses,” those ancient Greek deities of literary, visual, lyrical and scientific inspiration. It was a place envisioned as a sacred shrine, a modern temple of the imagination, dedicated to a religion of beauty, of transcendence and transformation and, perhaps most surprising of all, of visceral, physical moments of deep aesthetic pleasure.

I hope to have more to say about both art and museums as distinctively modern and distinctively sacred institutions in the future.

Louis A. Ruprecht Jr. is William M. Suttles Professor of Religious Studies and Director of the Center for Hellenic Studies at Georgia State University. His latest books include Winckelmann and the Vatican’s First Profane Museum (Palgrave Macmillan 2011), Policing the State: Democratic Reflections on Police Power Gone Awry, in Memory of Kathryn Johnston (Wipf and Stock 2013) and Classics at the Dawn of the Museum Era: The Life and Times of Antoine Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy (Palgrave Macmillan 2014).