Gary Laderman

Like countries around the world, the US is getting hit and hit hard by the coronavirus pandemic. Sickness, suffering, and death, as well as social pandemonium tied to health resources, unemployment, and isolation, are constantly looming over, if not intruding dramatically into, our lives, a situation that will likely last for the next few months, at least. And as we are seeing in NY, but evident in cities around the globe, communities are being overloaded with dead bodies that are potentially dangerous and generally sequestered from living relations.

The collective awareness of death, and the impact of massive numbers of dead, will no doubt affect the private and public worlds of Americans living through this pandemic. If the past is any indication of what’s to come, it is one of those historical moments that will have lasting and profound consequences for how Americans think about death, react to it, and live with the dead. Sadly, human history is full of examples of “mass death,” often tied to war and disease, that are usually pivotal periods for living communities.

Think, for example, of the “Black Death,” referring to periodic epidemics of bubonic plague that ravaged Europe over the course of the fourteenth century especially, killing tens of millions of people. In the aftermath of that particularly long and painful experience with mass death, new attitudes toward death began to emerge that challenged, and helped shift, dominant Christian views on death tied to such theologically notable concepts like judgement and resurrection.

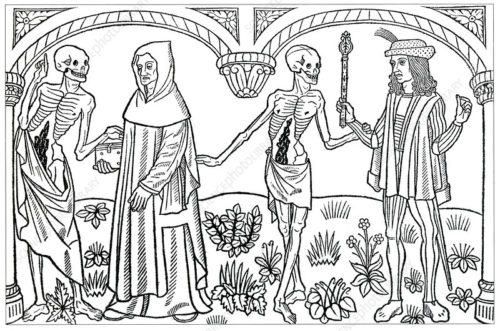

The period after the Black Death initiated monumental shifts in how individuals understood their own mortality. The rise of macabre imagery in its wake, such as the “danse macabre” or dance of death, in which a sexless rotting corpse leads a dance with the living, who come from every and all social classes, communicated multiple morally-charged messages–about fear and uncertainty, death in life, embracing life, and the individual encounter with Death. Another revealing artifact to emerge after this period of great suffering and widespread loss of life was the “ars moriendi,”or the arts of dying well, which depicted and scripted the transition from life to death at home, in bed, and the imagined drama surrounding the fate of the soul. Both of these examples hint at the significant ways individuals reoriented their lives in the face of mass death and expressed new forms of self understanding and purpose.

Though not nearly on a comparable scale as the Black Death, US history too has been ravaged at times by mass death. On the other hand, one could even say, as many have, that America herself is borne out of mass death and genocide, with millions of native peoples and enslaved Africans killed in the pursuit of nation-building. The long and massive deaths of these two populations is now as critical to the historical narrative as remembering the Puritans, and the memory of their dead continues to haunt and challenge popular, longstanding claims about American exceptionalism.

The American Civil War is another, more historically bounded, example of a collective experience of mass death and the lingering, and sometimes immediately felt, psychic and social repercussions left in the aftermath. With over 600,00 dead from battle and disease, Americans confronted death and human carnage in the 1860s in ways they had never experienced before. But the war also led to radically new and complicated attitudes that contributed to altered landscapes of death that did not exist before the war.

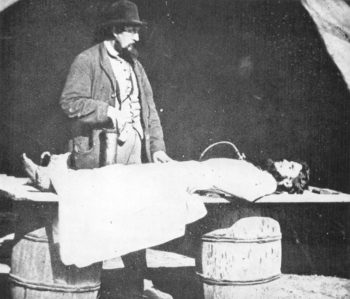

On a very material level, the war literally changed how Americans viewed and interacted with their dead. Before the Civil War, no embalming; after the war, embalming becomes a crucial element of American funeral rituals. Before the Civil War, no funeral homes; after, funeral homes begin to proliferate and soon in the early twentieth-century a full fledged industry begins to take shape, with funeral directors in charge of the dead. The carnage from the Civil War and the peculiar traumas it brought to the living seeded a revolution in modes of disposition in the US that held sway and determined what counted as an appropriate funeral for much of the twentieth century.

On a more immaterial level, the loss of life and the inability to control the fate of the dead during the war contributed to an increasing emphasis on the life of the spirit and on the importance of memorializing the dead for the living after the war. On this religious front, the war opened up various spiritual options for imagining how the living connect with the dead and sustain bonds of affection, in some cases tied to Christianity but in other cases, like the popularity of spiritualism at the turn of the twentieth century, more religiously free floating.

The Vietnam War in the 1960s and early 70s is still another episode of mass death, with fatalities from that war tallied at near 60,000, though the collective impact of these dead on Americans was magnified at the time by media coverage of body bags and the brutalities of war. Like other historical periods with extreme exposure to death and many dead, the war took place in a time of great social upheaval and crisis, and made a lasting impression in the cultural milieu that took shape, and continues to shape, American politics.

In a word, the Vietnam War contributed to the politicization of the dead. The reassuring words from religious and political leaders who drew from a patriotic fount full of sacrificial imagery and the rhetoric of martyrdom lost its sway in American society during and after the war. The familiar and common efforts to tie death to national symbols and meanings was challenged by protesters, family members and friends of dying soldiers, religious activists, and others, who questioned the morality of this war and the “masters of war” demanding more and more martyrs. The living would not abide by official declarations, and the dead would not stay silent. Indeed, some have linked the Vietnam War to George Romero’s pathbreaking 1968 horror film, Night of the Living Dead, which is about the dead returning to eat the living.

The dead do return, and often as a result of the experience of mass death and social chaos, are represented in ways that reflect some of the critical shifts and changes in how people understand the meaning of death, and the purposes of life in the face of such extraordinary circumstances and collective loss: a dancing cadaver; an embalmed corpse; the hungry dead. Today we are living in a different world from these examples, and entering a critical stage as the pandemic begins its surge here in the US. As we keep hearing, the social landscape will be dramatically altered by this pandemic, but it will also be shaped, and haunted, by the dead and the impressive communal sorrow that will mark this turning point.

Gary Laderman teaches at Emory University. His forthcoming book is “Don’t Think About Death: A Memoir on Mortality.”