This is our first in a series of discussions about the PBS Masterpiece series Indian Summers, airing Sunday nights at 8 pm EST on PBS. Sacred Matter’s managing editor Michael J. Altman and Ilyse Morgenstein Fuerst, assistant professor of religious studies at the University of Vermont, will offer their reviews of the series as it airs in the United States. NOTE: THERE ARE SPOILERS

The first two episodes of Indian Summers show take place in 1932, the late stages of imperial India in all its messy complexity. As the series begins, we’re told that “only a few thousand British civil servants” rule all of India, and many of these Britons spend their summers in Simla (Shimla), at the foothills of the Himalayas, to escape the heat. (Get it? Indian summers?) The characters are European and Indian–with a myriad identities within those imprecise categorizations–and we are clearly meant to see British India from each of these perspectives.

IMF: I started Indian Summers with an immediate oh, no: the opening sequence includes Indian drums, sepia-toned images of British India, and bursts of paint-splatter that conjure Holi. It seemed a little too predictable, a little too reliant on images, sounds, and significations of what an English (or English-speaking) audience already knows about India. I braced for the worst.

Thankfully, it didn’t come.

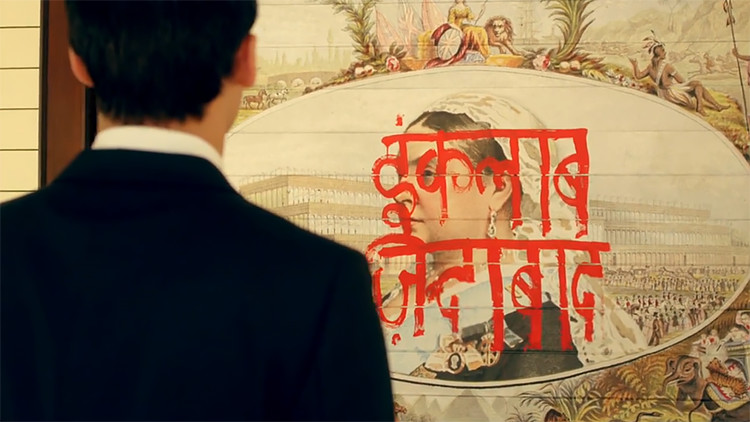

And, perhaps inevitably, the perspectives seem to purposefully capture all the diversity of India. There’s siblings Ralph and Alice Whelan, he’s a high-ranking British civil servant, who has spent his whole career and life in India, and she’s returning after fleeing her husband. There’s Dougie Raworth, a missionary entirely devoted to his work but neglectful of his wife, Sarah (but who also tried to kiss Leena Prasad, a Christian Indian who teaches [?] at the missionary school). There’s Aafrin Dalal, a Parsi in the civil service, and his family, who rely on his wages. Aafrin’s sister, Sooni, is an activist of sorts, and the first episode finds her scrawling “inqilab zindibad” (“Long live the revolution!”) across a portrait of Queen Victoria. Aafrin and his secret Hindu lover, Sita, go against both their families and traditions to keep their relationship going. There are Scots (Ian and his uncle), old doyennes (Cynthia Coffin), and “the native” who owns his own tea plantation (Ramu Sood). There’s also Bhupinder, Ralph’s trusted servant, who we learn grew up on their estate and has known both Alice and Ralph since childhood. There is Chandru Mohen, an almost-assassin of Ralph, who–in just these two episodes!–is quickly highlighted as someone with a personal connection to Ralph but portrayed as a terrorist; his assassination attempt is spun as revolution in the name of Gandhi’s Congress Party.

Head spinning yet?

The series is, in some ways, off and running: there’s been a political action (Sonni’s daring paint job) and a repression (her painting triggers a false investigation of cholera in the neighborhood, to provide police cover to catch the painter red-handed, literally). There’s cross-religious love interest (Aafrin and Sita, and, momentarily, Leena and Dougie). There’s caste and purity, race and ethnicity issues all over the place. In other ways, however, it is slow moving, and I’m not entirely sure where some of the plot lines and subplots are headed. A lot has happened, but nothing has really evolved yet.

All of that said, for a depiction of late imperial India, this series has a lot of rich–and dare I suggest, on point–details.

MJA: Yea, I had the same fears initially. I was worried this would end up being a typical upstairs/downstairs British drama except the downstairs would be a continent of brown people. But I think one of the first two episodes of the show does well is diversify the characters on both sides of the British/Indian dyad. So, for example, Sarah stands out as a fascinating character. She’s jealous of Alice and most of the other British characters and her status as a missionary wife keeps her on the outside. On one level this signals the distance that the British civil servants tried to maintain from the missionaries, lest they be accused of meddling in Indian religion. But on another level this signals the class divisions that Britons brought with them into South Asia. Since the earliest missionaries in the 1800s, there was always a class divide between the more working class missionaries and the more socially mobile civil servants. Meanwhile, Sarah is also struggling with her husband’s inattention to her and constant focus on his missions work. It reminded me of how William Carey, one of the first missionaries to India, pursued his missionary work to the point that his wife went mad.

I also think the show does a good job reflecting the sorts of Britons that went to India. There are those who grew up there like Ralph, merchants looking to make a living like the two Scots, missionaries, and random Americans looking to marry up in the world. As I started watching the show I kept thinking, “Is this just going to be Downton Abbey but in India?” Happily that is not the case. If anything, these are the Britons that couldn’t cut it in Downton Abbey and were shipped off. And they know how to party much better than the Downton folks.

IMF: There are a few details worth mentioning:

Gandhi factors here in ways I didn’t–but probably should have–expected. Sooni’s deeply invested in the Home Rule movement, an obvious connection to Gandhi. In the wake of Chandru Mohen’s attempted assassination of Ralph, civil servants gather for a meeting, and draft a letter; Ralph insists that this dispatch include the language of fighting fire with fire, referencing that they ought not rest “until Mr. Gandhi and his Congress Party are subdued.” Later, when a reporter makes his way to see Ralph, he notes that the guest book holds the signature of M. K. Gandhi as a previous visitor to the compound. The invoking of Gandhi is historically appropriate–it’s 1932, after all, and at that time, Gandhi was perhaps at his height of notoriety and (relative) power. It is also, of course, a way for an English-speaking audience to connect to a set of events, locations, and people that are imagined as foreign (in time or place). Who hasn’t heard of Gandhi? Who wouldn’t immediately hear “good guy” upon mention of his name? It’s an insta-drama: all the English folks portray Gandhi as a bad guy, a leader of a terrorist outfit; we necessarily hear that and perk up, regardless of whether we could find Simla on a map.

“Terrorist” as an epithet is fascinating in this context. In the second episode especially, the civil servants throw terrorist around as if they’re running for election in the US almost 100 years later. To a British or American audience, the juxtaposition of a never-ending newscycle in which Muslims are de facto terrorists with these Indians of unknown or multiple religious backgrounds is a bit jarring, in a good way. Just as it is almost impossible to understand Gandhi-as-terrorist, it is challenging to comprehend how Sooni (a Parsi), Chandru Mohen (a Hindu), and “the Congress Party” (presented as an all-Indian party here) could all fit the same bill.

The intersections of race, class, caste, and religion are done well here, even in just a few episodes. Leena and Dougie rescue a boy that she describes as “cursed” because of his “mixed blood,” and later, Dougie asks, in an intense moment, if that’s what happened to her as a girl. Aafrin and Sita’s clandestine meetings between saris in the bazaar and in a graveyard hit on issues of religious and caste intermarriage. In one of the first scenes of the series, we see an Indian washer cleaning a sign on the British (Only) Club which reads: “NO DOGS OR INDIANS.” Aafrin has a “good” civil service job, but his family complains about the filthy, small quarters they’re forced to share. Ralph eats comfort food after nearly being shot, but it’s a thali, cross-legged on the floor, using his right hand, as an Indian might (after all, we’re expected to remember, he’s never lived anywhere else–does that make him Indian?). Any student of mine (or Mike’s) knows that it is nearly impossible (and usually not advisable) to divide race, class, caste, and religion into neat and tangible boxes, and that all of these identifiers and identifications are operative, usually all at once. Indian Summers, so far, balances this well.

MJA: One thing I’d add to that list. It really is a beautifully shot show. Ralph’s massive house, the forests around Simla, and the mountain views are picturesque. And I mean picturesque. Colin Mackenzie would be proud. So, there’s a way that this television show that is representing the British Empire in India is also representing India through the traditional tropes the British Empire used to represent India. If that makes any sense.

IMF: That makes lots of sense! Here’s what I’m looking forward to seeing as we keep watching:

We’ve got Hindu-, Parsi-, Christian-, and Muslim-Indians represented (and named as such) so far. Will the trope of communalism rear its head?

How will the home rule/independence movement continue to factor to the narrative? Since it’s TV, I want to see which of the Britons will turncoat, since that’s bound to happen, right? (Bad joke. But a good one, too.)

MJA: What I’m keeping an eye on:

Is there going to be some redeeming quality for Sarah, the missionary’s wife? The episode ended with her getting a friend to investigate Alice’s supposedly dead husband. I don’t know where that could lead or what problems that will cause down the road.

Gandhi. You already mentioned this, but I’m curious to see how he figures in this story. There was a passing reference to Bhagat Singh in episode two, but the only other major historical figure mentioned has been Gandhi.

Also, will there be any Theosophists in this show? Gotta have some Theosophists.