Carolyn M. Jones Medine

In Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind, Scarlet O’Hara comes upon Ashley Wilkes engaged in, perhaps, the first physical labor he has ever done. When Scarlett asks, what is to become of them in the post-Civil War world, Ashley puts down the axe and with his eyes “journeying to some far-off country where she could not follow,” he says,

In the end what will happen will be what has happened whenever a civilization breaks up. The people who have brains and courage come through and the ones who haven’t are winnowed out. At least, it has been interesting, if not comfortable, to witness a Gotterdammerung…A dusk of the gods. Unfortunately, we Southerners did think we were gods. (732)

The loss of the slave-supported aristocratic way of life that he has led leaves Ashley rudderless, in contrast to Scarlett, who will embody the post-war scalawag, accepting the loss of the Southern plantation way of life and rebuilding with Darwinian entrepreneurial ruthlessness. Ashley laments, “…I am fitted for nothing in this world.”

I begin with Gone With the Wind, that most popular example of the post-Civil War historical romance to enter its shadow, Thomas Dixon, Jr.’s The Clansman, which formed the plot of D. W. Griffith’s epic film, Birth of a Nation. The novels are linked: Mitchell read and appreciated Dixon’s work and verified its influence on her own. Thomas Dixon, Jr. (1864-1946), a North Carolinian, was, at various times, an actor, a lawyer, a politician, a Baptist minister, and a writer. He left the ministry in 1895 after seeing a stage play of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, to lecture and to write about the South and the Negro. He, interestingly, was never a member of the KKK. Dixon said that he disagreed with violence except in the case of self-defense, which included the defense of white Southern values, exemplified, particularly, by white women. In his childhood, he witnessed the lynching of a black convict who was accused of rape. Dixon’s mother told him that this was justice. From that moment, he never doubted the rightness of the Klan, and he celebrated it in his novels.

Dixon’s historical romance, The Clansman, is the centerpiece of his “Reconstruction Trilogy”– the best-selling The Leopard’s Spots (1902), The Clansman (1905), and The Traitor (1907)–each novel involving a different set of characters. The novels trace the Southern reaction to the loss of the Civil War, “occupation” by the Northern Reconstruction powers, particularly the Freedmen’s Bureau, and the rise and “fall” of the Klan in its first phase.

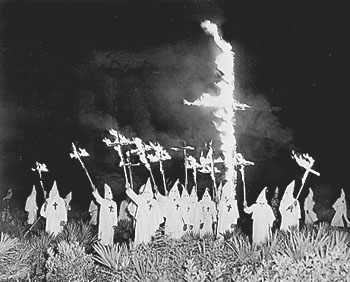

The Ku Klux Klan, in this first phase, was mythically founded on December 24, 1865, by a group of Confederate veterans in Pulaski, Tennessee. (Its actual founding probably was in May 1866.) The name of the Ku Klux Klan was derived from the Greek word kyklos, meaning “circle,” and the Scottish-Gaelic word “clan.” Its first “Grand Wizard” was Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest (1821-1877), though he turned away from and tried to disband the organization in 1869, because of the intensity of its violence. The Klan combined a philosophy of white supremacy, which was on the rise throughout the post-war United States, with violence, both to control the free African American population and to prevent enfranchisement.

The order was one of a number of racist societies in the South meant to represent a faceless, uniformly white population and to inspire terror:

Its strange disguises, its silent parades, its midnight rides, its mysterious language and commands, were found to be most effective in playing upon fears and superstitions. The riders muffled their horses’ feet and covered the horses with white robes. They themselves, dressed in flowing white sheets, their faces covered with white masks, and with skulls at their saddle horns, posed as spirits of the Confederate dead returned from the battlefields. (Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th Edition (June 2015): 1-2)

As The Clansman demonstrates, the Ku Klux Klan was a structure within which white men acted out their vision of southern society and through which they used terror to enforce those visions. The KKK may have been the United States’ first cellular, to use Arjun Appadurai’s term from Fear of Small Numbers (2006), terrorist structure: it was and is covert, local and de-centered, mobile, and opportunistic, multiplying by opportunity and interpersonal connections.

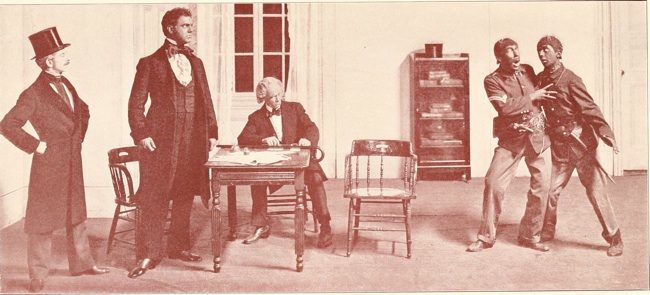

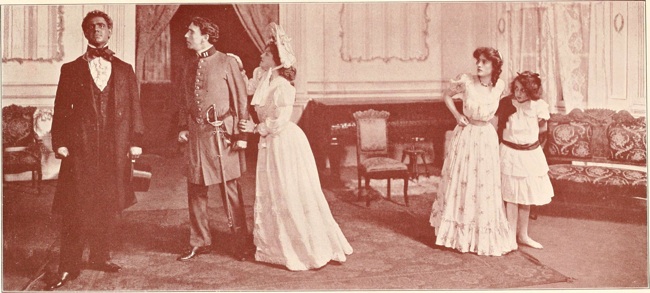

The Ku Klux Klan of The Clansman was strongest in the mountains and the Piedmont of North Carolina, though Dixon set the novel in South Carolina because of its larger black population. Dixon’s work and understanding of the post-Civil War south was highly influential. The Clansman was both a novel and a play. Though the play’s performance was banned in many cities in the South, it had high attendance where it was performed. The Clansman, with The Leopard’s Spots, is the basis of the second half of the film Birth of a Nation.

The Clansman begins as the Civil War, “the long agony” (Clansman, 4) ends and the “Negro question” rises as the key issue. The novel centers on Ben Cameron, a courageous young Confederate who will become the Grand Dragon of the South Carolina KKK, and Elsie Stoneman. Elsie is the daughter of Austin Stoneman, a thinly veiled impersonation of Thaddeus Stevens (1792-1868), the Radical Republican Congressman. Stoneman, “The Old Commoner” (41), in contrast to the aristocratic Southerners, is diabolical in his hatred of and desire to dominate the South.

The novel is pure romance, on one level: Elsie and Ben fall in love, and she turns against her father’s politics. When Austin Stoneman becomes ill, his family relocates to Piedmont, South Carolina so he can recover. He falls into a coma, and while he is absent from the story, his son Phil falls in love with Ben Cameron’s sister, Margaret. Cameron marries Elsie and Phil marries Margaret, bringing the families–and North and South– together against “black rule,” miscegenation, and Southern loss of sovereignty. If marriage is the private restoration of purity and order, The Klan is the public instrument.

The Klan, for Dixon, is made up of the aristocrats of the South. As Nel Painter points out, there are no poor whites in The Clansman: “In Dixon’s work all whites display the attributes of power, not only wealth and education (formal or informal), but also height, slenderness, and refinement. These are the natural rulers of Dixon’s made-up society, in which whites unfitted for leadership do not exist” (“Tom Dixon and His Clansman,” 124). This emphasis on nobility ties the novel, first, to the romance genre, from medieval romance to Sir Walter Scott, whose work was a model for the Southern cavalier, and, second, to Dixon’s emphasis on “clan,” Old Scotland as a sign of Aryan purity.

Romance

Medieval romances involve High Romance and Adventure, often including a religious crusade, the conquest of an enemy, and the rescue of a captive lady, or any combination of these. When written in prose, the romance genre mimics history, suggesting a truthful and faithful representation of the past. In The Clansman, for example, Dixon puts in Abraham Lincoln’s mouth—rightly, of the younger Lincoln—the theory that blacks are alien and inferior and should be re-colonized to Africa. He makes Lincoln a mystic hero of the South, ignoring the deep hatred of Lincoln in the South and the Southern use of his election to leave the Union.

Cathy Boeckmann, in A Question of Character: Scientific Racism and the Genres of American Fiction (2000), ties Dixon’s work to medieval romance, to the romances of Sir Walter Scott and to the Americanized form of James Fennimore Cooper. Typically,

Scott’s historical romance involves a conflict between two different groups, separated by visually recognizable ethnic or national differences. As Cooper reshaped the form, the two groups become two races that meet “the challenge of race against race [in] mortal combat” (275). The outcome is already determined, hierarchialized, and “right” order will be restored.

The major characters in romance are or are revealed to be, as Ben Cameron will be, noble–Ben is called “Sir Knight” (Clansman, 301). The genre involves quest, by men, a narrative mode deployed to bring together multiple characters in various combinations. The plots almost always involve disguise and marvels or some form of the supernatural, just as the Klan, as we noted earlier, deploys a supernatural dimension to inspire terror. Dr. Cameron becomes the figure of the supernatural: a mystic seer and high priest of the Fiery Cross ceremony at the end of the novel, justifying the lynching of Gus.

The romance genre also involves ritual and ceremony. Knights are, as Ben Cameron is, ceremonially armed. Heraldry, with symbols, like “scarlet circle and white cross on each man’s breast” and on the horses (Clansman 315), are part of the romance and of this novel. The use of the number three is also an element of romance: hence, the three letters: KKK. Romance also involves a Chivalric Code, and the Klan’s is “Chivalry, Humanity, and Mercy,” traditional values of the medieval romance, and Patriotism, the American addition. The knight’s triumph, in this the romance, over the chaos monster, here, the black beast exemplified by Gus, the rapist, benefits a group or nation.

Clan to Klan

The particular “nation” in the novel is the transplanted Scots of South Carolina. Ishmael Reed, in “The Celtic in Us” (2010) writes: “In South Carolina, which some view as an overseas territory of Scotland–the Confederate flag is a duplicate of the flag of Scotland and much of KKK symbolism is derived from Scottish lore” (329). Boeckmann explores the “boiling up” of the Scottish blood in the novel: “In Dixon’s fiction, a threat to the code of American democracy and Anglo-Saxon purity surfaces in Reconstruction. Eventually, that threat is met when an even older code, the code of honor of the Scottish clans, is evoked. The Klan comes into existence because the descendants of the Scottish clans have inherited the racial tendencies that make a defense of white supremacy inevitable” (15).

The Scots represent white Aryan “civilization” (Clansman 291), not just American democratic principles. They are the hidden royalty within America, with “‘the heritage of royal blood’” (119). They are pure, and the height of purity is the white Southern woman. Marion Lenoir, the woman whom Gus and his men rape, and who, with her mother, commits suicide is the symbol of Scottish purity. The narrative describes her as belonging “to the aristocracy of poetry, beauty, and intrinsic worth” (255). Gus, the black Captain of the Union League, is her opposite, a ‘”thick-lipped, flat-nosed, spindle shanked negro, exuding his nauseating animal odour,’” as Dr. Cameron, Gus’ former master and the principle spokesman for scientific racism and the mystic seer in the novel describes him.

When Gus enters the Lenoir home, we see the white-constructed beast: he “stepped closer, with an ugly leer, his flat nose dilated, his sinister bead-eyes wide apart gleaming ape-like, as he laughed: ‘We ain’t atter money!’” (304). The rape of the white woman is the symbol of the violation of the South itself and of white masculinity. Ben Cameron predicted, “‘the next step’” of black rule “‘will be a black man’s hand on a white woman’s throat’” (262). In the rape scene, “the black claws of the beast sank into the soft white throat” (304). Marion’s rape represents the violation of purity and sovereignty.

Black men raping white women is, of course, not the source of miscegenation in the south, but for Dixon, as Nell Irvin Painter writes, “rape was a crime whose only victims were white women” (121). The two marriages in The Clansman may return the American family to national and, for Dixon, “natural” order, but the color line can never be normalized, and sex across it is the ultimate violation. Sex was, as Painter suggests, the most emotional issue of southern race relations. It was “the thing underlying post-war white…hysteria” (118).

Gus’ raping Marion unleashes hysteria in the Klan who gather in a cave under the ledge from which she leaps: “Strong men began to cry like children” (323); “Some of the white figures had fallen prostrate on the ground, sobbing in a frenzy of uncontrollable emotion. Some were leaning against the wall, their faces buried in their arms” (324). The Klan is born from clan hysteria. The Durkheimian collective action of the group opens up a new cultural form, a new religion–that of the Lost Cause. Effervescence reinterprets old symbols and generates new symbols, especially that of the Fiery Cross.

The Fiery Cross is the ultimate romance symbol. Sam Allison, in Driv’n by Fortune: The Scots’ March to Modernity in America, 1745-1812 (2015), argues that it links the Klan’s imagined Scottish past to the depressing present of the Lost Cause through Sir Walker Scott’s The Lady of the Lake and other works:

In much the same way that nineteenth-century Scotland invented a tartan and clan history that it never had, the nineteenth-century South invented a Scottish past that it never had…Plantation owners in the “Old South” saw themselves as clan chiefs with a military as well as a social role to play, and Scotland’s flag–the St. Andrew’s Cross–became the war flag of the Confederacy, the Southern Cross.

Allison argues that Scott may have invented the image of Fiery Cross. In the novel, it is the triumphant “symbol of an unconquered race of men” (Clansman, 326), pure men, with the “courage of the lion, the cunning of the fox, and the deathless faith of religious enthusiasts” (343). When Dr. Cameron, as mystic high priest, mixes the blood of Marion Lenoir with the water of the stream that runs through the cave–in a dark image of the Eucharist–and puts out the Fiery Cross in this mixture, he purifies Marion and inaugurates a new religion, sacramentalizing and ritualizing lynching, restoring white supremacy and “civilization,” and authorizing white masculine power that will be used on other black sacrificial victims.

Final Thoughts

Later in Gone With the Wind, Rhett Butler makes a scathing evaluation of Ashley Wilkes’ Gotterdammerung. Invoking Darwinian competitiveness, he says that the Ashley Wilkeses of the world deserve to die out because they will not fight. Dixon’s vision of the Ku Klux Klan, embodying this notion, is simultaneously–and oddly–modern as well as medieval. Dixon’s medieval aristocrats embrace and act out Herbert Spenser’s application of the Darwinian struggle to the human realm, which fed virulent late 19th century racism. This modern, scientific development updates and combines with an imagined past of knights and fair ladies, and brings a weird sense of logic to terror–and, on one level, Dixon and his Clan/Klan win the ideological struggle.

Dixon’s novels are scary for two reasons. First, because they, clearly, articulate the unspoken feelings and thoughts of so many white Americans of his time–and of ours. Second, set in the romance genre–and in a plot–The Clansman has a strong impact, even though it is not particularly well written. Dixon wrote, in the preface to his last novel, “The Flaming Sword, that “A novel is the most vivid and accurate form in which history can be written.” The sympathetic reader might agree, developing an investment in the characters’ lives and allowing the logic of character and plot to move him towards sympathy with the supposedly besieged Southerners and into the “logic” of racism. How much more powerful Birth of A Nation must have been, wide in scope, deploying new techniques of film-making, and being “authorized” by being the first film ever screened at the White House. Richard Brody, in The New Yorker (2013), argues that the most problematic thing about the film is that it is a work of art.

The Clansman and the rest of Dixon’s trilogy are less art than manifesto. We, recently, experienced the modern expression of Dixon’s and Griffith’s racist thinking and “values” in another manifesto: that of Dylann Roof, the young man who perpetrated the Charleston, S. C. church shootings. Roof is a contemporary echo of Dixon, so similar that we shiver as art, once again, becomes life.

Roof argues that black on white violence is epidemic–indeed, minority violence, for him, is a global epidemic. African Americans, his particular concern, are dangerous “lower beings” with low impulse control; they “are stupid and violent.” But, like the whites in The Clansman, he argues, “At the same time they have the capacity to be very slick.” Roof, like Dixon, urges violent reclamation of the nation: “It is far from being too late for America or Europe…But by no means should we wait any longer to take drastic action” to enforce white culture, which is “world culture.” Roof chose to “stage,” reminding us of Dixon’s plays and Griffith’s film, his act in South Carolina, for the same reason Dixon sets his novel there: “I chose Charleston because it is most historic city in my state, and at one time had the highest ratio of blacks to Whites in the country” (emphasis mine). He continues, “We have no skinheads, no real KKK, no one doing anything but talking on the internet. Well someone has to have the bravery to take it to the real world, and I guess that has to be me.”

Ashley Wilkes said that he was fitted for nothing in this world. The current sense, among American whites, particularly of white males, of disenfranchisement leads these misfits to find fit in violent action. Roof represents the kind of “lone wolf” domestic terrorist that a digital, cellular, age can create. Thomas Dixon, Jr., in his time, ended up a lone voice, in many ways, but he kept taking to “the real world” his southern racism. Lone voices draw followers, however, and as Stephen King writes in the “Afterword” to 11/22/63, reminding us of another powerful film moment, generated by another lone wolf, “If you want to know what political extremism can lead to, look at the Zapruder film. Take particular note of frame 313, where Kennedy’s head explodes” (1088).

Carolyn M. Jones Medine is a Professor in the Religion Department and the Institute for African American Studies at the University of Georgia. She researchs Southern American literature and religion, with an emphasis on women’s literature and on theories of religion, focusing on postmodern and postcolonial theory. She is co-editor of Teaching African American Religions (Oxford University Press, 2005).