It’s not what you think. Or maybe it is what you think. On the other hand, it doesn’t matter what you think, because you are probably wrong about drugs in Amsterdam, no matter what your “experience” was when you were in your twenties traveling through Europe.

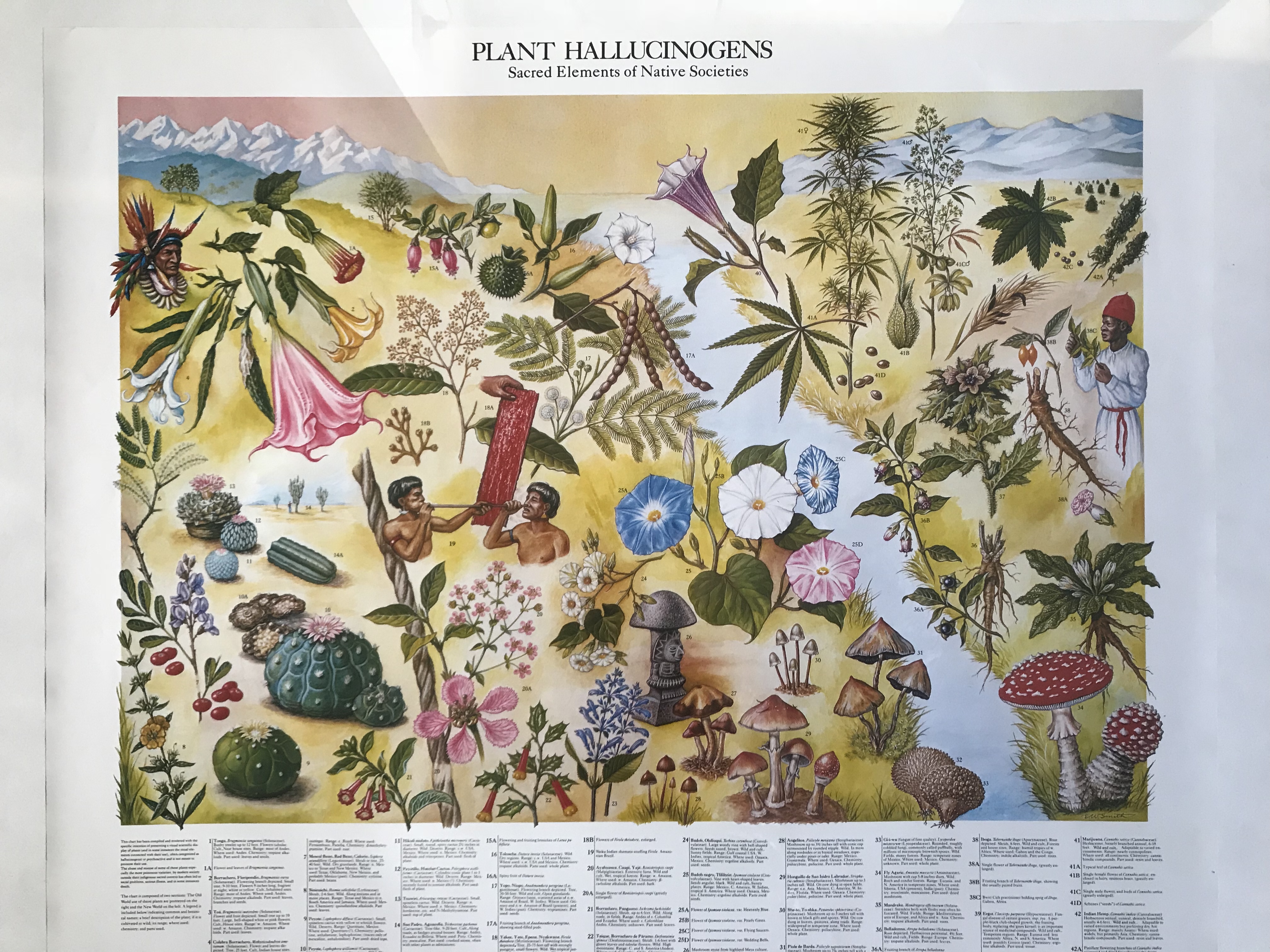

I flew to Amsterdam to get a taste of the drug scene for a week in November. For research. Really and truly. This summer I started researching a book exploring connections between drugs and religion, focusing on the US, when I had a revelation: for the scholarly purpose of comparative analysis, why not go to the global pilgrimage center for drug use and see if, how, where, and why religion intersects with drug consumption in more of an international context.

What triggered this international research revelation? A friend casually mentioned that there is a Hash Marihuana & Hemp museum in Amsterdam, and when I investigated (and I should mention, as you will see, there is a museum in Barcelona as well), the idea to go in the early stages of research hit me like a ton of bricks, and so I started concocting my plans. First step: make a connection with someone at the museum and see what transpires.

I introduced myself in an email to the contact address on the website and was pleasantly surprised when I got a response within a day or two from Gerbrand Korevaar, the curator there who proved to be incredibly helpful and generous with his time. In the course of our early correspondences, I made an uncharacteristically immodest move and suggested that perhaps the museum sponsor a public event where I might discuss some of my research in front of a few people.

He enthusiastically embraced the idea but also immediately let me know that the museum would not have the funds to pay an honorarium, which of course was fine with me and never even entered my mind given the fact that I basically invited myself–a move most self-respecting academics would never do (lol). What he wrote back to me, however, was priceless and brought me great joy when I read it, a joy that is worth more than any euro figure could be. He wrote: “We can’t pay you an honorarium but we can give you all the weed you want.” I knew when I read those words that he was joking, but still, it is one of the stand out communications in my professional life.

After that conversation the stage was set, and before I knew it the museum partnered with the not-yet-opened Poppi Museum, which is currently raising funds for what looks to be an innovative, informative, and interactive new drug museum in Amsterdam, to cosponsor “In Drugs We Trust: An evening on the marriage between psychoactive substances and religious experiences” during my visit there. It was the first time the museums cooperated and organized a public event and I am sure it will not be the last.

You would be surprised what you could learn about drugs from a week in Amsterdam. The dynamic, complex, and politically-charged role of drugs in the Netherlands is not that different from the scene in the US, especially as cannabis and psychedelics continue to move into the mainstream here. My week in Amsterdam was full and eye-opening in many ways, but the evening of public discussions around religion and drugs was definitely a high point (the other research-related insights will likely be the subject of a separate blog). The promotional materials on the web and posted around town promised a “multisensory event, with talks, music, and a mystical ambiance,” and the setting, a room in the storied Lloyd Hotel in the Eastern Docklands of Amsterdam, contributed greatly to what was simply a magical, if not quite mystical, vibe. The place was sold out too, full of people who paid for admission sitting on chairs, floor pillows, and hemp carpets.

It is my sense that people in Amsterdam, and America as well, want to talk openly and publicly about drugs in our lives, considering the essential, complex, and vital roles they play. Throwing religion into the mix only enlivens and invigorates that public discussion, I’ve found, because of the varying ways people define and understand both “religion” and “drugs.” Our evening on drugs in Amsterdam reinforced this sense and, much to my pleasure, gave me even more valuable data to work with in the endeavor to write about how drugs have become a new, primary source for religious—or spiritual, if you prefer—life in contemporary society.

The other speakers were not academics like me, thankfully, since that would have surely been the ultimate buzzkill. Instead, these were on the ground, creative leaders and participants in various aspects of drug culture, all willing to highlight or at least reference the religious—or spiritual if you prefer—dimensions of those cultures. Noted television journalist and producer, Steven Kampier, served as our amiable and informed host for the evening.

The first participant, Canadian Chris Bennett, is a well-known activist, author, and speaker on the relationship between grass and spirituality. Although he was not physically present at the event, he provided a video for us with his explorations of these connections in the world’s religions and religious cultures, as well as a moving testimonial of his own spiritual experiences with cannabis (which included his encounter with Revelations in the New Testament).

The other two speakers were present in the flesh, and both focused on ayahuasca, a particularly controversial drug in the Netherlands given recent legal issues but one that is exploding in popularity there, here, and probably everywhere. Writer, lecturer, activist, and a longtime leader in the ayahuasca movement in Amsterdam, Arno Adelaars, brought much of the crowd to the event, I think, and his experience and knowledge of sacred plants in the old world and the new brought a broader perspective

to the evening, though his own personal stories and anecdotes gave the audience a glimpse into the more intimate details of his interactions with the drug. When we learned during a pregame dinner that the evening’s events would be streamed, Arno requested that no live video be allowed for, as he memorably put it, “YouTube and Facebook want to be my friend, but they are not my friends and I want nothing to do with them.”

Finally, Melanie Bonajo, an internationally renowned artist from the Netherlands, brought some clips of her film, “Night Soil #1/Fake Paradise,” which explores and exposes ayahuasca experiences of women and those within LGBTQ communities, voices that are often not heard in our current psychedelic renaissance. Her film and comments were brilliant and illuminating, I found, and her statement that the sacred plants are finding humans and offering their help, rather than being discovered by humans as a new form of medicine, has stuck with me. Here is a little clip.

As for myself, I chose not to disclose whatever drugs I may or may not be taking, nor whether any drugs I may or may not have taken led to any sort of religious—or spiritual if you prefer—experience (although I have referenced tripping on acid here and there). In short, I went all academic and intellectual, rather than experiential and personal, and tried to point out and elaborate on three points about religion and drugs. At one level, a bad move, as this was not the place or time to get too cerebral; but on another level, it was sheer joy to make a bad move like this, as I found the reception and push back to some of my comments quite stimulating.

The first point didn’t seem to bother anyone and I assume is generally accepted by most: humans are drawn to altered states of conscious, seek out forms of intoxication, and seek to go beyond the bounds of ordinary consciousness. This is behavior not uncommon in other animals, and humans have been tripping (to be overly colloquial) down through the ages and across multiple cultures around the world. The other obvious point here is that this activity has long-been a source for religious—or spiritual if you prefer—revelations, meanings, practices, politics, and life generally.

The second point is where things went a little haywire. I tried to suggest that in contemporary society, psychoactive drugs—of all kinds, from hard to soft, legal or illegal—have become a primary, central, and pervasive source for religious—or spiritual if you prefer—life. Ranging from the most extraordinary and out of this world experiences with ayahuasca to the most ordinary, everyday, and routinized experiences with prescription pills, many of us do indeed follow the motto “in drugs we trust” rather than trusting in the monotheistic God of old.

This led naturally to my last point—which I guess is the point of my academic life more generally: people are religious in ways they don’t recognize. My book will, I hope, explore how the various and varied drug cultures ubiquitous in contemporary society can be deeply and profoundly religious (or spiritual, you know the drill by now), and how these cultures are replacing and overtaking conventional forms of religion. While psychoactive substances have been around and used throughout human history, our particular historical moment seems especially ripe for the entanglements of drugs with religious and spiritual life. I mentioned two specific, and simultaneous trends that have aroused my research curiosity: the rise of big Pharma and the rise of the “nones” or that segment of the population who claim no religious affiliation on surveys.

As I mentioned, the responses and discussion were lively, but too short. I wanted to pursue some of the questions raised about big Pharma and the “nones” that I’m thinking about. When an older gentleman asked rather incredulously if I really believed prescription drugs can be tied to spiritual development, I tried to explain why and how that seems to me to be the case, but was drowned out by others’ questions and comments. When some expressed encouragement about my efforts to carve out a conceptual space somewhere between “medicinal” use and “recreational” use to explore these religious and spiritual dimensions, time ran out before we could get into a deeper discussion.

Even when the event officially ended, conversations continued among many who remained and wanted to keep talking about the linkages, and differences, between religion and drugs. The anecdotes and comments I heard from individuals afterward were revealing, and quite similar to what I hear from people I speak with about the project in the US—the topic allows them to understand and talk about their relationship to certain drugs, and certain types of religious activity, in a new way.

Gary Laderman teaches at Emory University and is writing a book on religion and drugs.