Have you heard the new mantra about psychedelics? It’s no longer “turn on, tune in, drop out,” as the religious prophet Timothy Leary once said, but the more respectable, “clinical trials demonstrate psychedelics have therapeutic efficacy.” Welcome to the brave new world of psychedelics on the American landscape, no longer thriving on the margins or underground as an illicit vehicle for consciousness expansion and cosmic tripping, but now entering the limelight of mainstream public culture as medicine that heals.

The flashpoint for the psychedelic revolution on the horizon is not back to the future Haight-Ashbury, but the historically powerful medical research centers across the country, and around the world. You don’t need to drop acid yourself to “change your mind,” to play off the title of Michael Pollan’s recent bestselling book. Just read the medical research and your mind will likely change about how tripping can change one’s mind, one’s health, and one’s state of being. The widespread news about therapeutic psychedelics, and the increasing numbers of Americans moved by the medical studies, Pollan’s book, Avelet Waldman’s memoir on microdosing, A Really Good Day, and other popularizing psychedelic media coverage to try some for themselves, suggests that something is indeed changing about what it means to heal and what is culturally acceptable in this pursuit.

The opening a few months back of a Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research at Johns Hopkins University is a landmark event on the cultural landscape for many reasons. The potential medical and therapeutic applications of supervised consumption of psilocybin, LSD, MDMA, and ketamine for depression, Alzheimer’s, PTSD, and other difficult and often gut-wrenching afflictions and conditions is hard to imagine at this point, but already numerous  scientific studies and personal testimonies of the healing possibilities of psychedelic use point to groundbreaking advances.

scientific studies and personal testimonies of the healing possibilities of psychedelic use point to groundbreaking advances.

The fact that this center opened in one of the most prestigious medical schools in the country also signals to the world that the use of certain kinds of drugs that were once, and still are, demonized and criminalized, can in fact be used legitimately and have socially beneficial value to individuals and to society. If the medical community becomes convinced through research, scientific investigations, and clinical trials that psychedelics can heal and bring health and wellbeing to unhealthy, hurting, suffering individuals, it will likely be a game changer in the ongoing efforts to sway attitudes and policies around drugs and the pursuit of good health.

And that is the key unlocking the door of legitimacy for psychedelics, and other drugs as well: “good health.” The authorized gatekeeper attempting to control boundaries and classifications of drug use, the Federal Drug Administration, has granted some psychedelics “breakthrough status,” meaning a regulated green light for further research and development for therapeutic purposes. Psychedelics are likely to move from their current ambiguous legal status to medicinally available via doctor’s prescription in the next few years, which will transform the lives of many people turning to these drugs, in the medicinal, not illicit, sense.

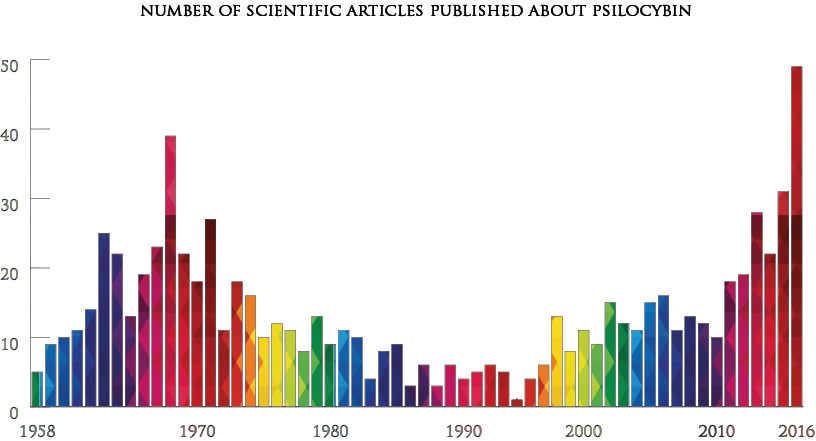

Even as the clear therapeutic promises demonstrated in research and clinical trials are highlighted in studies and media coverage, it is not uncommon to find some reference, often minor but sometimes more central, to a factor that is difficult to “bring under the microscope,” so to speak: the religious experiences of the subjects consuming the drug. The most important of these references is in the publication of an article on psilocybin and mystical experience in the journal Psychopharmacology, identified by Pollan as one of the three critical events from 2006 that helps to instigate the current psychedelic renaissance.

Here the innovative medical researchers at Johns Hopkins tried to put religion, in some form, under the microscope and reported and discussed what they discovered in their scientific, double-blind study. Their conclusion included this: “When administered under supportive conditions, psilocybin occasioned experiences similar to spontaneously occurring mystical experiences.”

Just what are mystical experiences, and what do they have to do with health? What is the relationship between health and spirituality? Is the search for healing and wellbeing religious, in some ways? Can drugs make a religious impact when they heal?

In a New York Times article covering the opening of the center at Johns Hopkins, the dilemma over how to factor in something identified as “mystical” (which is always in the same ballpark as the spiritual, or religious, right?) in the pursuit of healing a patient is broached, then dropped. Does the doctor “go there” when trying to explore the medicinal value of psychedelics? Neuroscientist Roland Griffiths, one of the authors in the 2006 study and the director of the Hopkins center, expresses some disquiet with the MEQ, or “mystical experience questionnaire” that is used to measure the intensity of the patient’s experience. He thinks it is misleading and is quoted as saying “That was a significant branding mistake, because awe is not fun.” Then he claims that there’s “something existentially shaking about these experiences.”

Taking a psychedelic drug to have an existentially shaking experience can be, under the right circumstances and under medical supervision, healthy and healthful for certain vetted and appropriate patients. What is the best way to “brand” an element of human experience that seems so critical to the overall impact of the medicine, but is difficult to operationalize and define and explain? To call it religious or spiritual or mystical would pose some conceptual and public relations problems in what is a thoroughly focused scientific and medically driven research trajectory.

Perhaps part of the concern is it might lead to confusion about the two dominant conceptual frames to think about drugs in society: they either have “medicinal” uses or they have “recreational” uses. What if someone wanted to argue that even healthy people should have access to psychedelics for purposes tied to “spiritual growth” or, if you prefer “health and wellbeing”? The science seems to point in that direction, as discussed in this article by clinical psychologist J. W. B. Elsey.

But it is in this more ambiguous, liminal conceptual space, between medicine and recreation, body and spirit, religion and science, that altered states of consciousness and mind altering substances do their best work. In some sense it doesn’t matter what words are used to describe elements of the current psychedelic renaissance—shaman or doctor; brain or consciousness; tripping or neurochemical transmissions. Even as their medical value is being uncovered in rigorous, scientifically-focused clinical trials with a relatively small number of patients who have very specific conditions, psychedelics are creeping into public consciousness, leading many at the micro and macro levels into new understandings of mind, body, and the ever elusive spirit, in the search for a healthy life.

Gary Laderman teaches at Emory University and is writing a book on religion and drugs.