Judith Weisenfeld

The plot of The Birth of a Nation features two intertwined narratives: a political story that moves from national unity to division in war and back to unity, and a romance in which a couple unites despite the obstacles the war presents. The Birth of a Nation is also, of course, a story about the subjugation of people of African descent, a process director D. W. Griffith frames as carried out by honorable white men who had no choice in the face of social chaos. Narratively, the subjugation of African Americans animates both the political story and the romance. Moreover, the racialized narrative supports the film’s religious frame of moral fall, conversion, and redemption projected on a national scale.

The film’s first scene [2:54-3:50] presents “the bringing of the African” as the source of disruption and national fall. It casts the work of abolitionists as perpetuating the problems set in motion by the unnamed parties who “brought” Africans. The conversion required to effect national redemption takes place through the founding of the Clan, the recruitment of members, and the mobilization of the group in a final push to subjugate free blacks and disempower their white allies. The pivotal scene [2:32:38-2:33:56] in this process of conversion features a ritual in the woods in which Clan members dressed in robes gather to avenge the death of a white woman, “a priceless sacrifice on the altar of an outraged civilization.” Affirming the group’s purposes and methods, they raise a burning cross, “the ancient symbol of an unconquered race of men,” before riding off for vengeance. Finally, after the Clan defeats the black soldiers and civilians threatening white families, the film ends [3:10:45-3:12:39] with honorable white northern and southern former enemies “united again in common defense of their Aryan birthright,” and looking forward to the restoration of a peaceful white Christian nation under Jesus’ benevolent gaze.

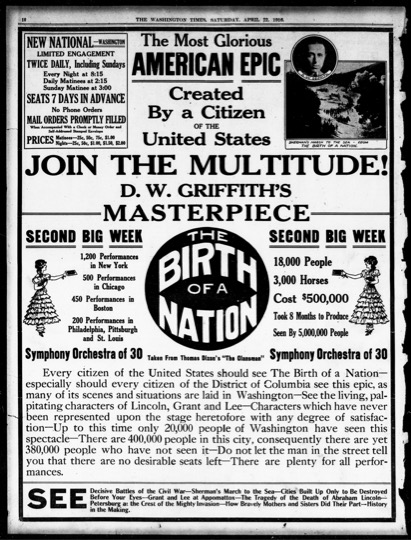

This is a great film, film critics and scholars have argued from the first exhibitions of Birth until today. It was great 100 years ago because of its ambitious scale in production (eighth months to film, featuring 18,000 people and 3,000 horses in a three-hour film) and in exhibition (shown in theaters accompanied by a large, live symphony orchestra playing an original score by Joseph Carl Briel). Critics and historians have also located the enduring greatness of The Birth of a Nation in its cinematic art. Here, Griffith’s mastery of close-ups, panning and tracking shots, and the refinement of cinematic presentation of causality and temporal and spatial relationships through montage, receive much attention. It is a great film, we have been told, and our understanding of its cinematic greatness can be preserved despite the film’s racialized narrative. In a reflection on the centenary of Birth in The National Review, film critic Armond White castigated those who are uncomfortable with this interpretation, focusing on an assertion in The New Yorker that “the worst thing about [The Birth] is how good it is.” White countered, “The fact is: The best thing about The Birth is how good it is, how its revolutionary techniques changed modern art…The worst thing is that such innovation was put to the service of racist ideology – and to the diminution of the sensitivity and aesthetic genius that made Griffith a great artist.” There is a sense among many film historians and critics, then, that Griffith’s presentation of the U.S as a white Christian nation under God’s protection, on the one hand, and his contributions to the development of cinematic art, on the other, can be separated and the latter salvaged.

In contrast to White’s view, and in sympathy with James Baldwin’s analysis in The Devil Finds Work (Dial, 1976) and James Snead’s reading in White Screens, Black Images: Hollywood from the Dark Side (Routledge, 1994), I reject the contention that cinematic innovation in The Birth of a Nation was simply “put to the service of racist ideology” and contend, instead, that racist ideology is constitutive of its visual achievement. Griffith’s demonstration of the emotional power of the close-up shot, for example, depended upon the construction of white racial innocence and inherent white female virtue, on the one hand (and both tied to a naturalized Christian nationalism) and the ever present specter of black male violation on the other. It is, of course, not “the African” who serves as the primary disruption in the film’s second half, but the scheming “mulattos”—the politician Silas Lynch and housekeeper Lydia Brown. James Baldwin argues that “these two dreadful and improbable creatures” draw the film’s negative energy to themselves through their lust after and envy of whites. Their presence offends the stability of the white Christian nation as much, if not more, than the black freedpeople and their white allies. Baldwin muses, “But how did so ungodly a creature as the mulatto enter this Eden, and where did he come from? The film cannot concern itself with this inconvenient and impertinent question” (Baldwin, 48-49).

Elsie held captive by Silas Lynch (George Siegmann).

Close up of a white child fearful of marauding black men outside.

Flora Cameron (Mae Marsh) fleeing from Gus and about to jump to her death from a cliff to escape.

Gus, played by white actor Walter Long in blackface makeup, introduced in the intertitles as “a renegade Negro.”

Lydia Brown (Mary Alden) and Silas Lynch, both played by white actors in blackface makeup.

Indeed, just as The Birth of a Nation focuses on the disruptive existence of the mixed-race characters without attending to their origins, so evaluators of the film’s “greatness” erase the constituent elements that produce its visual power. The Birth of a Nation is itself a “dreadful and improbable creature” that cannot be understood without accounting for its origins and component elements. As James Snead notes, the virulent “extra-cinematic codes” are, in fact, the “raw material” of its filmic innovation. He writes that “in unprecedented ways, film form and racism coalesce into myth here, seemingly myths of entertainment but ultimately ones political in nature, ones that continue to assert their presence today” (Snead, 38-39). If, as Armond White proposes, The Birth of a Nation’s “revolutionary techniques changed modern art” and displayed Griffith’s “sensitivity and aesthetic genius,” it wrought that change through representations of people of African descent as a political threat that must be contained and as the aesthetic and moral counter to whites, who alone receive Griffith’s sensitivity. The Birth of a Nation’s cinematic achievement was produced precisely through its racialized uses of the camera; Griffith’s approach and audience responses to it depended on long-standing extra-cinematic codes about religion, race, and people of African descent that persist to this day. Extending Snead’s argument, I contend that investments in particular visions of film art and understandings of greatness remain tied to Griffith’s racialized and religious structuring of modern cinematic art.

Mammy, played in blackface makeup by white actress Jenny Lee, serves as a gross caricature and counter to the film’s mediations on white female beauty.

While critics and historians have been willing to separate the historical content of The Birth of a Nation from the film’s cinematic achievements, the same cannot be said for responses to Ava DuVernay’s 2014 Selma. Aspects of the critical response to the film highlight the enduring power of the “dreadful and improbable creature” of Griffith’s wedding of a racialized narrative of white Christian nationalism to film form. Like The Birth of a Nation, Selma offers the case of racial conflict in a southern town as a window on questions about the relation of religious values to national identity. Where critics and film historians have been eager to bracket Griffith’s problematic historical narrative in favor of a pure cinematic experience, many responses to DuVernay’s Selma took the opposite approach. In complete dismissal of Selma’s mode of cinematic address, numerous white film critics, historians, political pundits, and politicians castigated DuVernay for her portrayal of President Lyndon B. Johnson as resistant to putting forward a Voting Rights Act, thus giving black civil rights leaders no choice but to organize protests such as the march from Selma to Montgomery. Joseph Califano, Johnson’s assistant for domestic affairs insisted in The Washington Post that the Selma campaign “was LBJ’s idea.” “Contrary to the portrait painted by ‘Selma,” Califano wrote, “Lyndon Johnson and Martin Luther King, Jr. were partners in this effort.”

Criticism of Selma’s portrayal of the president grew in intensity in the wake of the film’s broad release in early 2015. Maureen Dowd declared in the New York Times that DuVernay’s film had the potential to damage the young people DuVernay and producer Oprah Winfrey were devoting so much energy and money to ensuring could see it. Dowd wrote, “I loved the movie and find the Oscar snub of its dazzling actors repugnant. But the director’s talent makes her distortion of L.B.J. more egregious.” In the immediate wake of the highly-mediatized murders of Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, and John Crawford, the claim that DuVernay’s film presented a danger to the young black viewers Dowd slummed with to see it is troubling, but also revealing of the daunting obstacles black female filmmakers face and the unwillingness of many critics to extend to their work the serious engagement as art so freely conceded to Griffith.

That the film’s critics maintained a singular focus on the representation of a white male character in a film about black activism stems from the expectation that whites are the natural and appropriate subjects of all film narratives, an expectation grounded in The Birth of a Nation and that earlier films about the Civil Rights Movement, such as Mississippi Burning (Orion Pictures, 1988), cultivated. I certainly do not mean to argue that questions about how films based on historical events represent history are off bounds or that privileging the fictional nature of a film inoculates it against charges of willful distortion. It does not appear that DuVernay presented viewers with a willful historical falsehood or sought to vilify President Johnson. Sources such as Andrew Young’s interview about the Voting Rights Act and the Selma campaign for Dave Grubin’s 2012 American Experience documentary LBJ [0:55-1:41] narrated some aspects of the story much as Selma represented them. Others elements of Selma’s account could, indeed, be criticized for inaccuracy. But, in focusing so relentlessly on the depiction of Johnson, however, with nary a care for the portrayal of Martin Luther King, Jr., Diane Nash, John Lewis, or any of the other black activists, these white critics blinkered themselves to the film as a whole, unable to engage on its own terms DuVernay’s work that refuses Griffith’s “dreadful” approach.

For her part, DuVernay said, “I’m interested in having people of color at the center of their own lives. We don’t need to be saved by anyone. We do not need to have anyone sweeping in on a white horse or someone saving the day or assisting us in our own narrative.” The press picked up repeatedly on her defense that she did not “want to make a white savior movie.” She also didn’t make a black savior movie, and here is where I want to turn to the film as a film, an approach that was often absent in the controversies swirling around it. Examining DuVernay and cinematographer Bradford Young’s cinematic approach to the narrative reveals how they use close-up shots to both bring viewers into emotional connection with the Martin Luther King, Jr. character – in accord with Griffith’s use of the close-up – and to enlist the audience as participants in a way that depends less on centering King (as Griffith did with Lillian Gish, for example) than on obscuring him in significant ways.

In the film’s first moments we hear King’s voice as he practices his Nobel Prize acceptance speech before we see his face. With a fade in, we see his face as he says, “I accept this award on behalf of the twenty million Negro men and women motivated by dignity and a disdain for hopelessness.” DuVernay and Young do not make frequent use of frontal close-up shots of King’s face and, in this case, pairing it with the character’s assertion of connection to hopeful and dignified Negro men and women makes clear that the film features King, but it is not about him. When King delivers these lines at the Nobel Prize award ceremony itself, DuVernay pairs his words with devastating images of the bombing of Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church that killed Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, and Cynthia Wesley, underscoring a view of his work as situated in the context of African Americans’ struggle for life and justice.

Throughout the film, DuVernay favors shots where King’s face is partially or fully obscured especially when he talks about his place in the movement. In a scene featuring an exchange between King and Assistant Attorney General John Doar in which Doar tries to persuade King to place his own safety above participation in the march, King tells him, “I can’t hide. We can’t hide.” DuVernay and Young use a frontal close-up shot here, but pair the image with dialogue that shifts attention from King alone to him as one among the many people in the movement. Throughout much of the rest of scene, King stands with his back to the camera, his face obscured as he tells Doar that, although he would like to “live long and be happy,” he is not focused on what he wants but “on God wants.” By the scene’s end when DuVernay and Young return to a frontal close-up, King underscores the point that the march is about “a lot of freedom-loving people who worked hard to get us here.” In the film’s conclusion this transition from King to the participants is completed with the final shot, a bookend to the opening frontal close-up shot, showing King from the back and emphasizing the crowd of people before him. A. O. Scott recognized this character of the film and of the actors’ performances in his New York Times review, writing, “Dr. King worked in the service of the movement, not the other way around, and Mr. Oyelowo’s quiet, attentive, reflective presence upholds this democratic principle by illuminating the contributions of those around him. I have rarely seen a historical film that felt so populous and full of life, so alert to the tendrils of narrative that spread beyond the frame.”

From the final scene of “Selma”.

Lorraine Toussaint as Amelia Boynton in “Selma”.

Wendell Pierce as Hosea Williams and Stephan James as John Lewis in “Selma”.

DuVernay also uses numerous group shots – close, medium, and long – that underscore the importance of the many participants in the Civil Rights Movement at the local and national levels who contributed to its successes. The subject matter of a group action in Selma the form of a march certainly lends itself to this approach, but I think this sort of framing is deliberate and revelatory of a different way of using the camera. I have been thinking of these as collective close-ups, a visual approach that deemphasizes Griffith’s close-up as revelatory of inherent racial virtue and innocence and emphasizes virtues of common action toward the collective good. Historian Leslie M. Harris highlighted this element of Selma’s approach in her response for the American Historical Association’s AHA Today blog, writing, “The history of the civil rights movement challenges us to see varieties of leadership and participation: to understand an MLK who is more than first among equals but also part of the fabric of the movement. As fabrics are not made up of a single thread, so movements are not the work of a single leader – neither president nor King. Hundreds of thousands of people worked, lived, marched, died, changed, transformed. Selma coveys that complex history of many leaders, many activists, many heroes.”

Through this collective close-up approach, DuVernay also offers white viewers clues, to how they might position themselves in relation to Selma and the story it tells. She accomplishes this through her representation of Viola Liuzzo and James Reeb, both of whom were murdered as a result of their participation in events in Selma. We encounter them first as compassionate spectators of the televised events from the Edmund Pettis Bridge, so filled with compassion and indignation by the images of violence that each decides to heed the movement’s call for support. After they arrive in Selma, DuVernay locates them within group shots. Their presence is noteworthy, but they become part of the group rather than the center of the narrative, as DuVernay rejects the approach, inaugurated in The Birth of a Nation, that situates Christian whiteness as the necessary subject matter of film, particularly in relation to blackness.

Jeremy Strong as James Reeb in “Selma”.

DuVernay refuses a white savior story, and the black savior story is a collective one that brings black women into the frame in new ways that also counter the The Birth of a Nation’s racialized visual bequest. As Brittney Cooper wrote in Salon, “In this film, we see black women resisting, organizing, strategizing and cajoling. That we want to see even more of this tells us that ‘Selma’ is akin to being gifted a few acres of our own after too many years gleaning cotton in fields that have not belonged to us. A black woman has gifted this to us.” To many critics and historians steeped in the unacknowledged and powerful legacy of The Birth of a Nation’s racialized visual form, DuVernay’s cinematic offering appeared a “dreadful and improbable creature.” To those willing to embrace and value other approaches to film art and the narrative of American history and religion, Selma offers the opportunity to imagine a different cinematic future than the one Griffith charted for us.

Judith Weisenfeld is the Agate Brown and George L. Collord Professor of Religion at Princeton University. She is the author of Hollywood Be Thy Name: African American Religion in American Film, 1929-1949 (University of California Press, 2007) and her most recent project is the forthcoming New World A Coming: Black Religion and Racial Identity During the Great Migration (New York University Press, 2016). She can be followed @JLWeisenfeld.