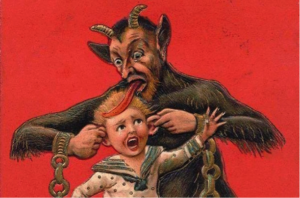

Krampus, according to Tanya Basu of National Geographic, “isn’t exactly the stuff of dreams: Bearing horns, dark hair, fangs, and a long tongue, the anti-Saint Nicholas comes with a chain and bells that he lashes about, along with a bundle of birch sticks meant to swat naughty children. He then hauls the bad kids down to the underworld.”

Krampus is the devilish, analogous form to the Catholic Saint Nicholas, the patron saint of children. St. Nicholas’ saint’s day falls in December, which encourages the relationship between St. Nick and the ever beloved, Santa Claus. Austria and Germany have one of the strongest relationships with Krampus—a German word meaning “claw.” Krampus, as part of folklore and legend, is part of a “centuries-old Christmas tradition in Germany where Christmas celebrations begin in early December.” While St. Nicholas rewards the behavior of good children, Krampus stuffs the naughty children into his sack and drags them away to his lair.

As part of Christmas tradition, folklore, and legend, children cower in fear at the mention of his name while also knowing, and acknowledging, the lengthy historical tradition to this tale. Like many legends, the accompanying art is often as or more horrifying than the spoken tale. There is a history of art that depicts Krampus just as Basu described. However, another figure often contrasted alongside Saint Nicholas is the figural Jew. Krampus, our Germanic beast of December, is considered devilish, evil, and malicious—many of the same stereotypes that Jewish men and women have consistently fallen privy to in artwork.

Based on a tradition of European art, it is my estimation that Krampus serves not only the role of anti-St. Nicholas, but also serves as an anti-Christmas and antisemitic representation of Jews and their relationship to the devil. I will pull art that depicts Krampus and children as well as images of Jews and children to compare their physiognomic features. Krampus serves as a phenomenological “other” to the beloved St. Nicholas figure, donning common antisemitic and anti-Jewish features. Krampus agitated European antisemitism during times of Jewish hatred, strife, and Christian malevolence towards their Abrahamic sibling.

Jewish Stereotypes: A Brief Introduction

According to Sara Lipton, renowned scholar in the field of Medieval European Jewish History (specifically through artistic exploration), the first distinguishable Jew emerged close to 1000 CE. The hooked nose often associated with Jews or Jewish people was not the first identifier that artists used of their Jewish subjects. Hats, not noses, around 1100 CE were used by artists to distinguish prophets, for example, in illuminated bibles. These markings of Jewish-ness were not originally the derogatory identifiers they morphed into. Slowly, over time, the identifiers once reserved for prophets of the Old Testament began to take on negative connotations and were applied to other Jewish characters. According to Lipton: “The range of features assigned to Jews consolidated into one fairly narrowly construed, simultaneously grotesque and naturalistic face, and the hook-nosed, pointy-bearded Jewish caricature was born.”

The physiognomic and stereotypically Jewish markings in art allow us to distinguish those who are Jewish from those who are not. Over time, these crude stereotypes morphed into hostility; a hostility that emerged most evidently in the mid to late twelfth century, according to scholar and author Bernard Starr. Stereotypes took the form of clothing with assigned colors, Jews with bags of money, or more crudely, Jews analogous to frogs, swollen with greed. However, one of the more peculiar and malicious forms of stereotypical imagery depicts the Jew or Jews worshipping the devil. The affiliation with the devil often places the Jew in hell, alongside the devil or smaller demons, and sometimes with horns, a goatee, or goat-like features. Our Krampus Creature is no exception.

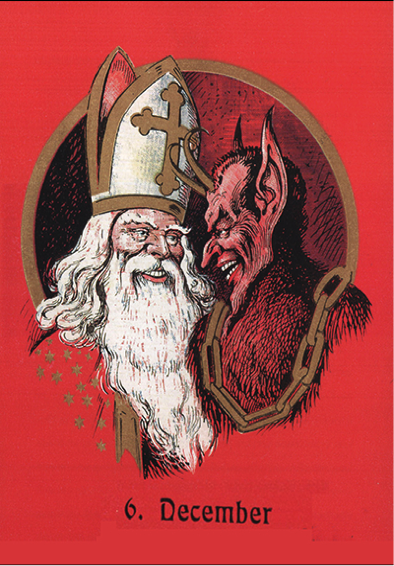

In images of the Krampus caricature, it is evident that his features—devilish, beard, grotesque, and long nosed—are meant to distinguish him from the jolly, rotund, rosy cheeked Saint Nicholas. If we consider Lipton’s and Starr’s arguments and explore the ways in which artists attempted to paint the religious-counter to Christians, Krampus’ “look” most clearly reflects a devilish character—someone, according to folklore, associated with Judaism, Jews, and Jewish dangers to Christianity.

Jewish Stereotypes Redefined

Krampus, the red-raced and horned figure to the right of Saint Nicholas, appears as evil as any conception of the devil. Saint Nicholas dawns a fully white beard and an identifiably Aryan face. His demeanor is jolly and cheerful, counteracting the evil grimace of his December yuletide enemy.

This Austrian postcard dates to the early 20th century but the stereotypes that Lipton and Starr describe emerged almost 800 years prior. Krampus, the evil child-snatcher, is beardless, but his hooked nose and naturally grotesque, devilish face indicates that he is not like Saint Nicholas; that perhaps he is a Jew, and perhaps he is the devil, but he is certainly not a revered Christian Saint.

Now, consider figure two: a wood engraving depicting yet another folklore—the Jewish murder of Simon of Trent. The murder of Simon of Trent was based on previous repeated accusations of Jewish ritual murder of Christian children. In this image, Simon is cast above Jewish men and women, and a devilishly horned figure. Artistic depictions of this scene often depict a Jewish woman having intercourse with a goat, Jewish men and a Jewish child inappropriately interacting with a sow, and the devilish figure watching.

While this horned figure may appear to be a hybrid enigma or non-human being, the facial features and physiognomic attributes seem devilish and goat-like— features commonly assigned to the caricatures of Jews.

Whether this figure is Jew or devil, he is not a Christian and no friend to Simon of Trent. The stereotypes applied to Jews throughout time were used as identifiers to distinguish Jew from Christian. This horned, hook nosed figure below Simon may be devil, but his characteristic features are the same as those used in depictions of Jews for centuries beforehand. Simon’s face is serene and sincere, maybe even Christ like, but his murderers look nothing like Simon. This purposeful juxtaposition of the murderous Jew and the martyred Christian child speak to the physiognomic features that are often characteristic of Jews on display in Christian art. This German wood cut dates to 1475, 300 years prior to the Austrian post-card and 400 years after Lipton’s date of emergent Jewish identifiers.

The Jew as devil—literally and figuratively—vigorously took hold. The Jews who were once associated with the devil spatially, like the image above, began to take on specific devilish features like horns. Jewish men and women over time became cast as Satan’s helpers or as demons/devils themselves. Moses is often depicted with horns and this led to widespread assumptions that Jews themselves had horns, often associated with a physical characteristic of the devil.

The stereotypes that are assigned to Jews over time have not always expressed hostility or hate. The horned Moses figure is grounded in biblical exegesis (Exodus 34:35). However, these particularities about Jewish figures over time trickle down into popular art. A horned Moses, once used to differentiate him as an Old Testament prophet, created an association with Jews and the devil. This devilish association became an artistic fascination with Jews as the devil’s henchmen or even as devilish demons themselves. Accusations of blood libels and ritual murders only heightened suspicions that Jews were demonically possessed and were most evidently non-Christian beings, perhaps even sub-human.

The myth of Krampus has pre-Christian origins, but is first incorporated into Christmas traditions in the 17th century. A devilish figure vehemently against St. Nick perfectly pairs with the emergence of the anti-Christmas, anti-St. Nick figure in Christian narrative. Krampus, over time, looks like the Jew the Christians feared, and takes on the devilish features the Jews were subjected to.

Is Krampus Jewish or Just the Devil?

There are no definitive statements that declare Krampus to be an antisemitic or anti-Judaic figure explicitly meant to juxtapose Jews with Saint Nicholas or align Jews with the Devil. However, accusations of Jews committing ritual murder of children has a chilling past. Krampus’ treatment of children indicates that he has similar tendencies to violence. Krampus’ actions, stereotyped physiognomy, and violence towards children across European folkloric history indicate that he fits the mold of “the Jew”—a malicious child-murdering people seeking vengeance against the Christians.

The Jew is consistently relegated to the “other.” As Lipton points out, the othering of Jews was not always indicative of hate or violence. However, the artistic features that once were saved for the prophets of the Hebrew Bible became visual describers of the Jew as other and the Jew as not Christian. Simply calling the Jew “the other,” gives way to antisemitic associations. Krampus, the anti-St. Nick, not only plays the role of the “other” but plays the role of the Jew as well.

Despite the features of Krampus growing out of hate meant to juxtapose St. Nick’s jolliness with the evilness of this emergent figure, he continues to grow gruesome and grim in art today. Current artists still create and re-create Krampus caricatures using grotesque features that have been characteristic of this malicious figure for centuries. Elliot Lang, Denver based illustrator, is no exception. His Krampus caricature retains the features of the 19th and 20th century illustrations. Just as the Jew is still identified by the hooked nose, Krampus is identified by his horns and outlandish appearance. Krampus is accepted, much like today’s Santa Claus, to be mythic. Then why do the artistic themes still take center stage? Why does a Krampus illustrated in 2018 look like the Krampus on an Austrian postcard? The caricature of the Jew consistently has been drawn, painted, or illustrated with a hooked nose, malicious features, or even horns. Krampus has similarly and consistently been the horned, devilish, child-snatching, malicious figure—the imagined non-human counterpart to the Christian holy man St. Nicholas. Krampus as Jewish, or as the anti-Christian, not only creates consistency between artistic depictions over time, but he fits the mold of how the Jew was imagined, who the Jew was understood to be against, and what the Jew supposedly looked like, in opposition to his Christian, Abrahamic brothers and sisters.

Madison Tarleton is a graduate student in the University of Denver & Iliff School of Theology’s Joint Doctoral Program in the Study of Religion. Her work intersects religion, media, and antisemitism. You can follow her @madisontarleton