Jason Bruner

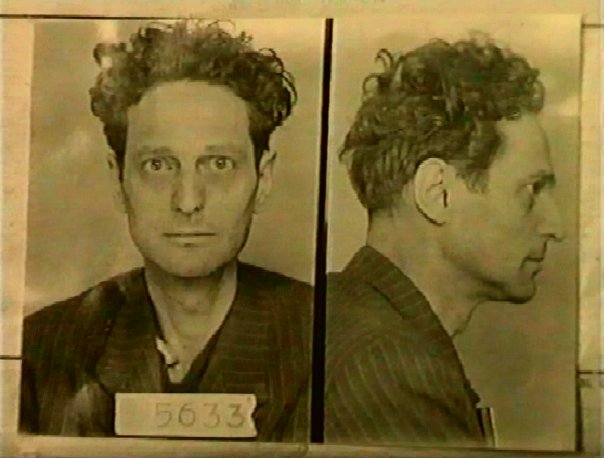

On March 4, 2018, Voice of the Martyrs, an American non-profit organization, released “Tortured for Christ” in selected theaters nation-wide. The film’s release was a one-night event in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of Richard Wurmbrand’s book of the same title, in which he described the evils of communism and his experiences of being imprisoned for 14 years in Romania, after which he was ransomed and sought asylum in the US, where he founded Voice of the Martyrs.

Voice of the Martyrs is dedicated to “serving our persecuted family worldwide,” by which they mean fellow Christians. A sense of persecution has not only formed American Christians’ self-perception, but it has also shaped the ways in which they imagine Christianity globally. Others even claim that there is a contemporary global war on Christianity, perhaps resulting in as many as 100,000 “Christians martyrs” per year. Over the last two decades, some Christians have leveraged these claims about anti-Christian persecution with respect to US foreign policy. It was no coincidence that the first version of the Trump administration’s “Muslim ban” contained a specific exemption (Sec. 5 b.) that seemed targeted to benefit Christians from the seven targeted countries, a version of a policy that has been repeatedly offered by Christian religious freedom activists since the mid-1990s, when Nina Shea and Paul Marshall galvanized political will around global anti-Christian persecution. In light of this history, I was curious to see how Voice of the Martyrs would not only tell the story of the “living martyr” who founded the organization, but also how that telling might illuminate American Christians’ politics of persecution under white evangelicals’ “dream president”.

The film opens on a darkened auditorium in the present day, a polished contemporary Christian worship band on the stage. Keith and Krysten Getty perform an original hymn before an audience, we are told, that includes missionaries who have served in countries that restrict proselytization. Images and video clips pass behind them on stage: Christians of the “persecuted church” worldwide, some happy, others somber, others seemingly in duress. The worshippers in the film’s opening sequence look much like those of us watching in the theater: white, mostly over 40, seemingly middle class, in theater-style seating.

The worship scene fades into darkness, and the soundtrack changes from applause to dripping water in a damp, dark concrete hallway. Layered onto that is the guttural rhythm of torture: someone grunts at the effort, another groans at the consequences. A guard hovers over a bloodied, frail, and dirty Wurmbrand, who is hanging from a bar. He demands answers. Wurmbrand, resolute, responds: “I belong only to Christ.” The beating resumes.

Here one encounters the central theme of the film: a single man with unwavering courage sees a governmental power for the evil that it is and, because of his faith, stands firm against it, regardless of the consequences. Wurmbrand is presented throughout the film as a consistent, principled, kind, morally flawless, and generally unproblematic character. While he is, of course, challenged severely, there is no development of him as a character in the film. As he was in the beginning of the film, so he is at the end. Such a formulation, of course, is deeply indebted to Christian martyrology, particularly that of the early Church and Reformation, and this framing of Wurmbrand’s life is essential to his identity as a “living martyr.”

While this lack of character development stems from the genre of Christian martyrology, it also is a consequence of the film’s connection with Wurmbrand’s book. The film has relatively little dialogue, with most of the telling of the story coming from Wurmbrand’s voice-over narration, which seems to have been taken almost verbatim from the book. These passages are frequently witty and moving. For example, he explained, “We made a deal with the guards—we would preach, they would beat, and everyone was happy,” at which everyone on my row laughed.

That the line got a laugh says something to the charm of Wurmbrand’s framing of these experiences. But it also says something about the film itself and how his suffering was represented. Judging from the reactions to the film from the people on my row, most of whom were with a group of elderly church women, they seemed to feel at home with the film, including (perhaps especially?) with its worship introduction and conclusion. It felt like a peculiar juxtaposition to be watching a film titled “Tortured for Christ” in a very spacious, fully-reclining theater seat. While the seats at the Mesa, Arizona Cinemark were undoubtedly comfortable, there was nothing in the film that pressed us to feel otherwise.

What I mean is this was no “Passion of the Christ.” In no sense did the film invite or encourage or even suggest for us to participate in Wurmbrand’s sufferings, despite the fact that Krysten Getty opened the film by reading Hebrews 13:3: “Continue to remember those in prison as if you were together with them in prison, and those who are mistreated as if you yourselves were suffering.” Instead of a mediated experience of suffering, we were meant to learn from his experiences. As a result, the torture scenes couldn’t really be described as graphic or gory. Once the audience was given an idea of what was about to happen, the camera panned away, or the film cut to an abstracted shot of concrete walls or barbed wire or a metal door, with the sounds of torture hovering in the abstracted air. If the “Passion of the Christ” was meant to be encountered as an “animated icon,” as Graham Holderness described it, then “Tortured for Christ” seemed to be intended as an extended illustrated sermon.

If this is the case, then what was the film preaching?

The points that appeared to resonate most clearly with the audience were on a few favored themes. I noticed knowing nods from those around me during the scene showing how Wurmbrand and his friends secretly distributed prohibited Christian literature inside books that had communist titles, and a laugh trickled across the theater when Wurmbrand explained: “Marx on the cover, Jesus in the pages.” They appreciated the subterfuge.

A number of lines that landed well had to do with communists. “Communism had robbed them of their humanity…only God’s love could restore them.” When the film focused on Wurmbrand’s stay in a prison TB ward, at which time he was near death for years, he observed that although many communists had likewise found their way into the TB ward, “not one of them died an atheist.” The moment that got the biggest reaction was when Wurmbrand’s prayers were interrupted by an irate guard, who quickly detailed all the things Wurmbrand had lost, concluding with the line, “What left do you have to pray for?” To which Wurmbrand, on his knees, quietly responded, “I was praying for you.”

These moments were rarely elaborated upon with any other commentary or narrative elements. Their very statement seemed to carry sufficiently their intended meaning. Individually, these episodes were the punchlines to brief episodes within the film that were usually separated from one another by cutting to a silhouetted shot of barbed wire or of bare tree branches. These punctuated didactic stories were selected because they had clear moral and theological points to be made. The audience’s reactions to each of these scenes felt quite similar to the ways I’ve seen evangelical congregations react to the key points of a sermon. In this sense, the film was edifying to the point of bordering on obnoxious, with its chief saving grace being found in Wurmbrand’s turns of phrase and pithy one-liners.

Wurmbrand’s story in the film ends with him still in prison (he was released in 1965, at which point he immigrated to the US). We see a brief montage of a handful of Christian martyrs from the communist prisons of Romania before the screen fades back to the worship service that opened the film. The band plays a translated version of a hymn written by a man who was imprisoned with Wurmbrand. This hymn was followed by a closing song, “In Christ Alone,” during which we were invited to reflect on our “response” to the film. Its lyrics were projected on the screen, prompting the theater audience to join in. The woman to my right dabbed her teary eyes on the last verse.

It is difficult to know what kind of genre the film aspires to be. Portions of the film incorporate documentary footage from Romania in the 1940s, and these were somewhat blended into the rest of the film, some of which appeared to be filmed almost in black and white. The film used three languages (Romanian, Russian, and English), which likewise gave it an aura of authenticity. But it is also the case that Wurmbrand’s story was contextualized liturgically, having been placed after the reading of Scripture and the opening hymn and before the two closing hymns. As such, it was intended to carry the instructive truths of a man who, because of his sufferings, claims he had “experienced a new form of Christianity, the kind where Christ’s love conquers all.”

What was this “new form of Christianity” and what else did it entail?

Published in 1967, Tortured for Christ quickly sold “more than 3,000,000 copies,” as one early edition proclaims. It’s easy to see why. Wurmbrand’s writing is terse and vivid, and he has a preacher’s knack for using remembered conversations and moments to illuminate theological truths or moral points. Wurmbrand portrays himself as clever and wise—a tireless and sincere evangelist with a resolute and principled faith.

Published in 1967, Tortured for Christ quickly sold “more than 3,000,000 copies,” as one early edition proclaims. It’s easy to see why. Wurmbrand’s writing is terse and vivid, and he has a preacher’s knack for using remembered conversations and moments to illuminate theological truths or moral points. Wurmbrand portrays himself as clever and wise—a tireless and sincere evangelist with a resolute and principled faith.

Though part autobiography and part survivor memoir, the book’s heart is ideological. Wurmbrand is desperate to make the case to the American public about the true stakes of the battle against communism: “Behind the walls of the Iron Curtain the drama, bravery and martyrdom of the Early Church are happening all over again—now—and the free Church sleeps.” This judgment, which is the book’s premise, is completely absent from the film.

But this diagnosis is analytically important because it allows him to further distinguish between what he believed to be essential to Christian faith from what which was only concerned with “nonessentials”. It is the “Underground Church” or the “persecuted church” which is most akin to the early Church. The Underground Church, as Wurmbrand describes it, is not coterminous with any particular denomination or tradition. He calls it the “naked” church that can have “no lukewarm members,” like the early Church. And like the early Church, the Underground Church has “no elaborate theology.” He dismisses much of theology as merely “truths about the Truth,” whereas in prison he learned to live in only the Truth, which is God. Other religious chaff was burned away in prison, where Wurmbrand said of Orthodox prisoners that there were “no beards, no crucifixes, no holy images,” and yet “they found they could get by without all these things by going to God directly in prayer.” The persecuted church was necessarily a bit more Protestant, in Wurmbrand’s estimation. And like among the first Christians–who didn’t have many Bibles–in prison, the “Bible is not well-known,” which he believed gave Christian prisoners an even purer faith.

This last point is interesting. Wurmbrand had memorized quite a lot of the Bible in multiple languages, but he says that there came a time during his imprisonment, where “hungry, beaten and doped, we had forgotten theology and the Bible.” This allowed a different kind of spiritual and mystical immediacy, made possible by forgetting that the “outside world” existed at all. It was this combination of things that made the faith of the persecuted church more authentic—closer to the first century Christians.

It was in the persecuted church in communist lands, according to Wurmbrand, that one could see “the Early Church in all its beauty, sacrifice, and dedication.” Persecution erased history. It also juxtaposed the authentic faith of those who were persecuted against what Wurmbrand took to be the languid indifference of Western churches. He would even claim, “I suffer in the West more than I suffered in a communist jail because now I see with my own eyes the western civilization dying.” He wasn’t one for understating a point, but this characteristically critical edge of Tortured for Christ was thoroughly polished smooth in the film, which made him into a kind saint who could teach us quaint truths while our feet were propped up.

In an audience that seemed to be overwhelmingly Christian, we were comfortable as we watched the film. There was no sense of impending threat, or that a totalitarian government would be putting the pressure on Christians in the United States. The absence of this feeling in the theater was something that I didn’t expect. I think this is due partly to the distinctions that Voice of the Martyrs has pretty consistently made since the organization was founded in the mid-20th century, distinctions which can be seen in Wurmbrand’s juxtapositions between the “West” and the “persecuted church.” In such an imagination of global Christianity, the expected role for Western Christians is to join in prayer and spiritual solidarity with persecuted Christians worldwide. It assumes, in short, that persecution is “over there.”

But what about the American evangelicals who reported to Pew in 2016 that they were finding American society becoming “more difficult” for them, a statistic which portended the overwhelming white evangelical vote in support of the Trump/Pence ticket later that year? I wondered what the experience of watching the film would have been like had Clinton won the presidential race in 2016. Instead, of course, American evangelicals now have their “dream president,” as Jerry Falwell Jr. put it, and that president is juxtaposed against a predecessor whom Tony Perkins labelled as being responsible for a global increase in Christian persecution.

In these developments, it is worth noting another dimension of Wurmbrand’s faith, one that was conspicuously absent from the film. While the film depicted his Christian faith as being radically cut loose from tradition, theology, and even the Bible, that faith also produced a particular diagnosis of political power. Wurmbrand’s fierce apologetics in Tortured for Christ against communism, which he called “a spiritual force—a force of evil,” weren’t countered with a full-throated endorsement of democracy. Rather, Wurmbrand marveled at communists’ centralized power, with an imagination that such power could be used for good. To that end, he hoped that Christians would win present-day “kings”—people who “mold the souls of men.” He believed that a centralized leader is much more effective at such a task, and in this sense he was in awe of the power of Stalin, Hitler, Lenin, and Mao to dictate policy, unlike, he says, the president of the United States. Remarkably, Wurmbrand’s main criticism of Hitler was that he “hated” communists, and that hatred allowed communism to spread, whereas Wurmbrand “hated the sin, but loved the sinner.” But even “love” has its limits, when one is talking about threats, Wurmbrand conceded. Near the conclusion of the book, he opined:

I am not so naïve as to believe that love alone can solve the communist problem. I would not advise the authorities of a state to solve the problem of gangsterism only by love. There must be a police force, judges and prisons for gangsters, not only pastors. If gangsters do not repent, they have to be jailed. I would never use the Christian phrase about ‘love’ to counteract the right political, economic or cultural fight against communists, seeing that they are nothing else than gangsters on an international scale.

The film about Wurmbrand ended by reminding us that he had found a Christianity in which “Christ’s love conquers all,” and one can see in this conclusion an articulation of an aspiration of American evangelicalism. But, Wurmbrand’s book of the same title ended with love’s strategic marginalization. Perhaps, in the theater, one can see the coexistence of these twin emphases in Wurmbrand’s life, which have become likewise infused within white American evangelicalism. After all, when one sees “American carnage,” then the authoritarian call to “law and order” might be seen as the necessary response, and one which requires the strategic setting aside of certain virtues, even as the elderly white woman shed tears in a recliner, softly singing, “No pow’r of hell, no scheme of man, / Can ever pluck me from His hand.”

Jason Bruner is assistant professor of Global Christianity at Arizona State University. He is a scholar of religious history with a particular interest in the history of Christian missions and the growth of Christianity in Africa and Asia in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. He can be followed @jason_bruner.