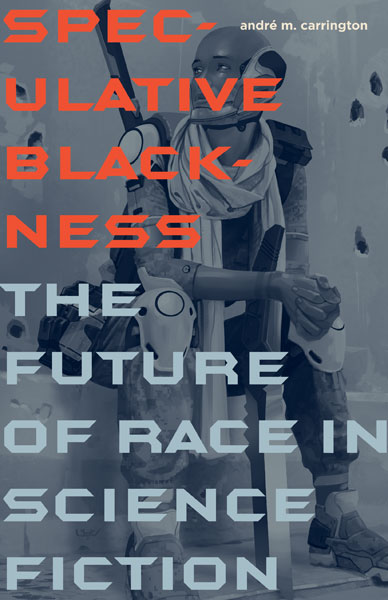

In our interview series, “Seven Questions,” we ask some very smart people about what inspires them and how their latest work enhances our understanding of the sacred in cultural life. For this segment, we solicited responses from André Carrington, author of Speculative Blackness: The Future of Race in Science Fiction (University of Minnesota Press, 2016)

1. What sparked the idea for writing this book?

I’ve always been a nerd and a science fiction and comic book fan. In graduate school, I got back into reading comics, and I gradually became more involved in media fandom online. The research for the book initially formed the basis for my doctoral dissertation, which was an exercise in taking popular media and fan culture seriously as venues for learning about the way people articulate their identities and their views of society. After living with an eclectic set of pop culture and intellectual influences for years, I was motivated to take things a step further and give my fellow scholars and the public a sense of what it means to dispense with the idea that science fiction, fantasy, and utopia are either inherently insightful or inherently suspect when it comes to the way they portray racial identity. I was determined to put forward an account of the deliberate, thoughtful work it takes to express critical ideas about race and gender in any artistic endeavor that doesn’t necessarily devote itself to that task, on the popular side of media, in forms like TV and fan fiction, as well as the more rarefied end of culture, in canonical literature and literary studies.

I’ve always been a nerd and a science fiction and comic book fan. In graduate school, I got back into reading comics, and I gradually became more involved in media fandom online. The research for the book initially formed the basis for my doctoral dissertation, which was an exercise in taking popular media and fan culture seriously as venues for learning about the way people articulate their identities and their views of society. After living with an eclectic set of pop culture and intellectual influences for years, I was motivated to take things a step further and give my fellow scholars and the public a sense of what it means to dispense with the idea that science fiction, fantasy, and utopia are either inherently insightful or inherently suspect when it comes to the way they portray racial identity. I was determined to put forward an account of the deliberate, thoughtful work it takes to express critical ideas about race and gender in any artistic endeavor that doesn’t necessarily devote itself to that task, on the popular side of media, in forms like TV and fan fiction, as well as the more rarefied end of culture, in canonical literature and literary studies.

2. How would you define religion in relation to your work? Where do you see the sacred or sacred things in this book?

The sacred and the profane are intertwined in many forms of Black vernacular culture. In my research, I see the sacred represented in fan works that treat the erotic meanings of popular texts in explicit terms and in the reverence that authors have for their forebears. I don’t think that describing authors and actors as “idols” or participating in “cult” followings are quite the same as holding a space for the sacred, but rather, I think that whether people maintain religious observances and beliefs or not, we learn to consecrate texts and authors, to appraise their value, through the same means that we learn how religious institutions perform that task. Ritual, pilgrimage, and ecstasy are not only metaphors when it comes to people’s devotion to cultural texts—these terms are really useful in theories of the practice of making genre traditions. I discuss the sacred and the divine as such where they’re associated with certain writers, including Jack Kerouac and Steven Barnes, in citations of Yoruba and Dogon cosmologies as the inspiration for fantastic tropes, in the fictionalized history of the Marvel Comics character Storm, and in other references to real and imagined matters of faith.

3. Can you summarize the three key points you’d like the reader to walk away with when finished?

- The overrepresentation of whiteness in science fiction and fantasy, on the one hand, and the emergence of fantastic, futurist, utopian, and other speculative narratives from within African American and Black Diasporic cultural frames of reference, on the other, are equally important to understanding race in fact and in fiction.

- Genre traditions like science fiction develop across media, notwithstanding the specific conventions they accrue within any given medium.

- To understand Black people’s involvement in speculative fiction, we can really benefit from revisiting the feminist science fiction movement. Writing from that era brought feminist thinking and activism to a space within culture where it had been marginalized in the past, and it remains vital to do the same work with race consciousness, affirmations of Black knowledge, and anti-racist thinking.

4. Who were intellectual models or inspirations for you as you wrote this book?

Samuel Delany, Jewelle Gomez, and Joanna Russ have written inspiring fiction as well as provocative criticism that I find valuable. Initially, I looked to Scott Bukatman’s book Terminal Identity as a model for the book I was writing, but I realized that I was doing something different enough to reach further afield. Robin Kelley’s Freedom Dreams, essays in Dark Designs and Visual Culture by Michele Wallace, and some material that emerged from fanzines, namely Jeanne Gommoll’s “Open Letter to Joanna Russ” and some of the self-referential commentary of fan fiction writers whom I came to admire became important touchstones along the way. I was also fascinated by a rhetorical device, chiasmus, as a structure for organizing the book as a whole and key concepts in it; the defining example of that device, for me, comes from the writing of Frederick Douglass.

5. What was the most difficult thing about writing the book? Did you encounter any unexpected problems or challenges?

Because I’m a college professor on the tenure track (now, I wasn’t always), writing the book was both part of my job and an independent objective. Reconciling the demands of teaching, pursuing professional development, mentoring students, being active in my campus community and professional associations, and getting other publications done without a sabbatical leave took their toll. My longtime mentor passed away and the editor who had contracted the book left his position, during the time I was making revisions. I underestimated how long it would take to edit the manuscript to meet the expectations of my editors and peer reviewers, but I was grateful that the review process was so thorough, in the end. I was fortunate to have editors who were so patient. It made me a better writer.

6. What’s the most unexpected response, critical or positive, that you’ve gotten about the book?

I was really surprised by a review that commented on the fact that it’s an academic book with a form that resembles other academic books. The publisher, Minnesota, is a founding member of the Association of American University Presses, and I’m a college professor, so I thought that would go without saying.

7. With this book done, what’s up next for you?

I’ve been doing readings and presentations on the book and its subject matter at bookstores and libraries since Spring of 2016, and I’m slated to do many more in the coming months. I’ve been writing about comics and topics in queer theory more since the book has been published, and I’m also starting a new book project on a medium that isn’t included in the book: science fiction radio drama, in the tradition of the War of the Worlds.

André Carrington’s research focuses on the cultural politics of race, gender, and genre in 20th century Black and American literature and the arts. His first book, “Speculative Blackness“, interrogates the meanings of race and genre through studies of science fiction, fanzines, comics, film and television, and other speculative fiction texts. His current research project, “Audiofuturism,” explores literary adaptation and sound studies through the analysis of science fiction radio plays based on the work of Black authors.