Judith Weisenfeld

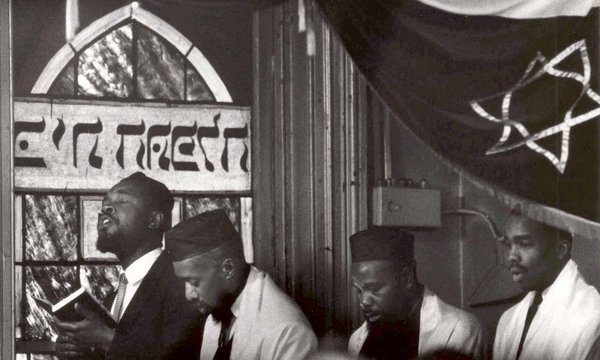

On October 4, 2015, the International Israelite Board of Rabbis, a body overseeing a group of congregations of Jews of African descent, voted to elevate Capers Funnye, rabbi of Chicago’s Beth Shalom B’nai Zaken Ethiopian Hebrew Congregation and first cousin to Michele Obama, to the position of Chief Rabbi. Installed on October 24 at a ceremony in his home synagogue, Funnye became the third Chief Rabbi in the history of the Israelite Board, which has its origin in the Commandment Keepers Ethiopian Hebrew Congregation founded in Harlem in the early 20th century by St. Kitts native Rabbi Wentworth Matthew and the first Chief Rabbi. The position had remained vacant since the death in 1999 of Rabbi Levi Ben Levy, the group’s previous Chief Rabbi, although Ben Levy’s son, Rabbi Shlomo Ben Levy, has helped to guide the member congregations in his capacity as President of the Board.

Given that there are currently about a dozen congregations in the U.S. under the authority of the International Israelite Board of Rabbis with a total membership of perhaps one thousand, it should not come as a surprise that press coverage of Funnye’s installation was limited, with Sam Kestenbaum’s article in the Washington Post’s “Acts of Faith” series, the most detailed and useful (Washington Post, October 30, 2015). Nevertheless, the event offers the opportunity to think about a variety of aspects of the relationship between religion and race in America, the shifting fortunes of small religious movements, and the challenges of recognizing diversity within groups that outsiders see as monolithic.

Most coverage of Funnye’s rise to leadership and speculation about the future of this movement has focused on his work to build ties to “mainstream” Jews of European descent despite a history of refusal to recognize members of the movement as Jews (Times of Israel, July 13, 2015). Funnye, who was ordained by the Israelite Board of Rabbis, received a B.A. and M.A. at the Spertus Institute of Jewish Studies in Chicago and is the first black rabbi to gain a seat on the Chicago Board of Rabbis. In addition, he is the first Chief Rabbi to have undergone conversion to Judaism, which he did through a Conservative beit din, an act he saw as affirming his identity as both an Israelite of African descent and a Jew connected to the broader Jewish world (Chicago Tribune, July 9, 2015; The Forward, July 10, 2015; November 13, 2015). The development of this movement from one focused primarily on reshaping black religious and racial identity to one seeking deep and ongoing engagement with Jews of all backgrounds is noteworthy, and builds on Matthew’s efforts in New York in the 1940s and 1950s. That Funnye was named as one of the 50 most influential Jews – one of four in the category of religion – in The Forward 50 2015 list demonstrates his success in achieving greater recognition among white Jews.

Perhaps more telling for our understanding of African and African diaspora religious history and culture than the connections Funnye hopes to build with Jews of European descent, is the International Israelite Board of Rabbis’ efforts to create a religious denomination that can incorporate a diversity of black Jews in the U.S., Africa, Latin America, and Israel. In fact, the majority of Funnye’s statement of vision during his campaign and evaluation focused on issues internal to the Israelite community. In a draft of a Unity Charter, the Israelite Board’s leadership proposed that they strengthen ties among the constituent congregations under the board’s theological and ritual authority and seek to admit new member congregations interested in affiliating with them as part of an Israelite denomination, distinct from the denominational structures and orientations of Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform. At the same time that the Board’s leadership propose a consolidation of authority, Funnye and the Board’s other rabbis have expressed a commitment to maintaining some openness to diversity of theology and practice within member congregations. Congregations in New York do not ordain women and maintain separation between men and women in worship, for example, while congregations in Philadelphia and Chicago “invite women to the Torah,” and Rabbi Debra Bowen serves as the rabbi of Congregation Temple Bethel in Philadelphia, which was founded by Rabbi Louise Elizabeth Dailey. How the Israelite denomination deals with the issue of women in leadership, clerical and otherwise, is worthy of press and scholarly attention.

Finally, the impact of Funnye’s assumption of the position of Chief Rabbi of the International Israelite Board of Rabbis reverberated among Jews of African descent in the U.S. who are not part of the Israelite movement. In an illuminating article, MaNishtana, an Orthodox Jewish African American blogger, surveyed the landscape of social media response to the announcement of Funnye’s election (Tablet, July 9, 2015) and noted considerable alarm. Many of those whose responses MaNishtana compiled objected to the notion that black Jews should or could be represented by a single individual and worried that Funnye would be accorded greater authority to speak for black Jews than they feel is warranted. Many highlighted the mainstream media’s fascination with black Israelites, who some Reform, Conservative, and Orthodox Jews of African descent do not recognize as Jews. Moreover, some felt that increased attention to and legitimation by white Jews of the Israelite Board of Rabbis as an authority for Jews of African descent would allow them to ignore issues of racism within their own congregations. The impact on Jews of African descent outside of the movement of Funnye’s elevation to Chief Rabbi and the move of the Israelite board to become a visible denomination of Judaism is also worth watching.

Judith Weisenfeld is the Agate Brown and George L. Collord Professor of Religion at Princeton University. Her most recent project is the forthcoming New World A Coming: Black Religion and Racial Identity During the Great Migration (New York University Press, 2016). She can be followed @JLWeisenfeld.