Scott Muir

This weekend, Bonnaroo Music & Arts Festival will celebrate “15 years of magic” with yet another four-day tour de force drawing 80,000 fans to a remote farm in Manchester, Tennessee. In a retrospective spirit, Dead & Company will close out the festival with the first headlining set of Grateful Dead music to grace America’s second largest stage since Phil Lesh & Friends headlined in 2006. The appearance represents a nod from the festival’s current corporate ownership to Bonnaroo’s roots in the Dead-spawned jam band subculture, while the grunge (Pearl Jam), electronica (LCD Soundsystem), hip-hop (J. Cole) and pop (Ellie Goulding) stars rounding out the top of the eclectic bill demonstrate the festival’s evolution from a subcultural summit for “heads” to a marquee mainstream music festival over the past decade. In the process, Bonnaroo has played a pivotal role transforming a social practice born out of the ‘60s counterculture and revived within the ‘90s neo-hippie subculture into a mainstream rite of passage.

Last summer, I covered the “Fare Thee Well” Grateful Dead reunion for Sacred Matters and reported the results of a survey exploring Deadhead attendees’ perspectives on religion, spirituality and the sacred. My respondents widely endorsed Gary Laderman’s notion that “Religion is dead” but the sacred lives on through sacrelized cultural phenomena…like the Dead. These Deadheads overwhelmingly reject both traditional religion and hard-line secularism, embracing the more fluid language of spirituality. Moreover, the vast majority report spiritual experiences at shows, affirm the notion of a shared spiritual community surrounding the band, and acknowledge the powerful influence of these shared experiences on their religious/spiritual identities. The exceptional devotion of Deadheads and the powerful impact of psychedelic rock on the “Woodstock generation” may be familiar tropes, but how widespread is this phenomenon of experiencing the sacred through live music?

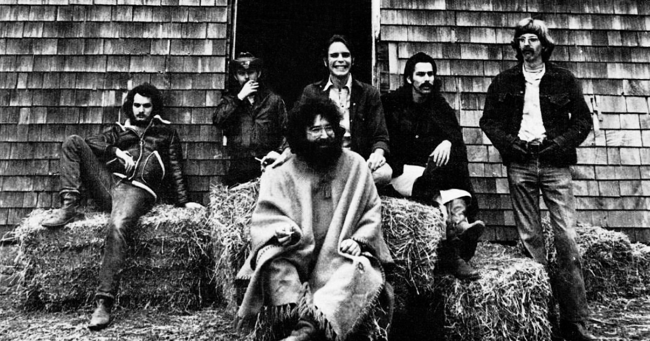

The genius of the Grateful Dead was to create something more than the sum of the thousands of concerts they played over the decades, an alternate universe grounded in a continual, collective reimagining of the 1960s counterculture—a “psychedelic tradition.” More crassly, Bill Graham and the Grateful Dead successfully commodified the psychedelic experience and established a sustainable space for it on the periphery of mainstream society. In contrast to the subversive symbolic power of Woodstock and the other big “pop” festivals of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, Deadheads posed no threat to the social order. Rather than forward a true counterculture, they contented themselves being a subculture, merely desiring to be left to follow their own rules rather than change them. And while all of the major “pop” festivals of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s were financial and logistical disasters, the Grateful Dead (eventually) proved enormously profitable, despite being utterly peripheral to the mainstream music industry.

As the Dead’s popularity grew and Jerry Garcia’s health declined in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, a wide variety of “jam bands,” including Phish and Widespread Panic, emerged to carry this psychedelic subculture forward and revive and redeem the multi-day camping festival format. Big rock and pop festivals were few and far between in the ‘80s and ‘90s and were often plagued by the same woes as their forebears (i.e. the riotous debacle of Woodstock ’99). Meanwhile, jam bands quietly founded their own grassroots events and pioneered promotional usage of the nascent internet to grow a virtually continuous, nationwide circuit of multi-day festivals of varying sizes known by insiders as “the Scene.” In contrast to their more hasty and ambitious predecessors, these festivals earned a reputation for running smoothly, peacefully and profitably, and consequently, were generally embraced by the locals and authorities as institutions, despite widespread awareness of the massive drug market that accompanied them.

Like the Dead, The Scene lacked the edge to truly challenge mainstream culture, but it did establish a fairly elaborate alternative, a robust subculture. The Scene is indeed a spectacle, and a remarkable social environment that deliberately counters mainstream norms. Attendees camp for days in densely packed “tent cities,” struggling against the elements and immersing themselves in crowds of enthusiastic dancers for hours on end. Interaction with strangers is expected and unavoidable, tie-dye t-shirts are standard garb, and a vast array of illegal drugs are sold, purchased and consumed casually. And at the epicenter, spontaneous co-performances reinforce cardinal values. Wild electric guitar solos give voice to radical subjectivity; the eclectic mixing of rock, jazz, blues, funk and bluegrass idealizes syncretic expression; and extended, fluid improvisations demand and reward exceptional openness to experience.

This alternative social world and its collective values render both traditional religious adherence and strict secularism equally problematic; both are perceived as closed-minded, heavy-handed and inauthentic. Instead, participants are encouraged to construct their own mosaic identities drawing from a wide variety of appropriated religious and secular resources marketed throughout The Scene. “Healing arts” tents where teachers offer yoga, reiki, herbalism, meditation, Ayurveda, crystal metaphysics, aura work, shamanic healing, etc. “Shakedown street,” the Scene’s makeshift marketplace, features booths bearing names like “Enlighten,” sporting art and paraphernalia bearing images of the Buddha, Ganesh, the Tree of Life, the Om sign, and a host of other extracted religious symbols alongside images of Jerry Garcia’s four-fingered handprint.

A committed core make the Scene their home, embracing a nomadic, gypsy-like lifestyle enabled by the formidable micro-economy The Scene supports. But for the middle-class majority of neo-hippies, such festivals serve as pricey periodic pilgrimages. They work more or less conventional jobs and save up their discretionary income to attend a few carefully selected festivals a year. While 65% of the 655 individuals I surveyed at 10 such festivals report that they rarely or never “attend religious or spiritual services/gatherings,” participants overwhelmingly affirm the notion that these festivals are themselves sacred social events. These respondents celebrate The Scene as a “completely different world” “detached from mundane life experience” which can serve as an “escape from the corporate world/society we are all forced to live in.” Over three quarters report that there has been a “spiritual quality” to their experiences at shows and over half of these say “frequently.” Moreover, 82% affirm that there is a “shared spiritual culture, connection or energy permeating this scene,” and the vast majority (81%) of these describe it as “very strong” or “somewhat strong.”

The original Bonnaroo festival in 2002, with a lineup utterly dominated by jam band stalwarts, was a summit for this subculture, the moment The Scene arrived. A grassroots effort spearheaded by the modest-sized, New Orleans-based Superfly Productions, the festival sold out over 70,000 tickets in a matter of weeks without any large-scale advertising or mainstream media coverage. Hundreds of such festivals eschewing corporate sponsorship and support from big music persist, attracting anywhere from dozens to tens of thousands of “heads” on the strength of their jam band-heavy lineup and reputation for serving “The Scene” alone, but none would attain the scale and status of those first Bonnaroo festivals.

Over the past 15 years, Bonnaroo has played a pivotal role adapting this “psychedelic tradition” and its multi-day camping festival form from this isolated subculture to yet another offering on the mainstream American cultural menu. Today, Bonnaroo is owned by the Clear Channel-spawned music conglomerate LiveNation, funded by huge corporate sponsorships and features artists spanning the entire spectrum of contemporary popular music, thereby drawing a much more diverse array of music fans. Drugs still abound, as well as a great deal of attire which symbolically invokes the ‘60s countercultural origins of the psychedelic tradition, but such symbolic outfits are now more likely to be culled from the “festival mix” line directly marketed for such occasions by major fashion outlets like FreePeople than purchased from a small vendor at the last festival. Throwing down several hundred dollars to go “do the hippie thing” for a weekend has become yet another commodified American pastime. Traveling to remote festivals, wearing tie-dyes and hippie dresses, smoking pot and experimenting with hallucinogens—these originally radically countercultural and later decidedly subcultural markers of difference have become increasingly mainstream. The point is not that such experiences have become mundane, but that they are ever more accessible and tractable—for those who can pay. “Tuning in” and “turning on” no longer seems to demand “dropping out” so much as discretionary income.

Many of The Scene’s faithful question whether its spirit can be sustained under such conditions. Dozens of respondents affirming the strength of The Scene’s spiritual culture explicitly qualify that their glowing testimonials do not apply to “big” or “corporate” festivals. But Bonnaroo owes its 15 years of success in part to the “magic” that fans have experienced in this massive, temporary community that keeps them coming back year after year. Later this summer, I’ll report on data collected at Bonnaroo and share my observations to draw further conclusions about the sacred and the “psychedelic tradition” as it evolves from counterculture to subculture to yet another item on the diverse menu of American mainstream culture for Millenials to appropriate as they construct mosaic spiritual-but-not-religious identities.

Scott Muir is a doctoral candidate studying American Religion at Duke University who writes on religion and live music, and religion in higher education.