This article is Part I in a three part series. Click here for Part II and Part III.

By Shalom Goldman

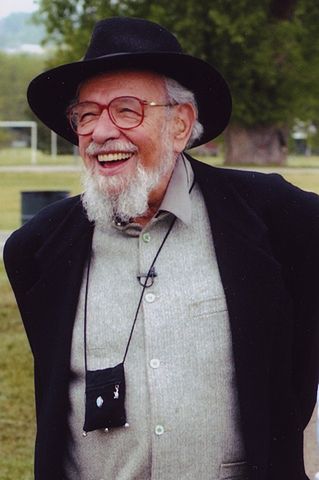

The reactions to the death last month of Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi may be a sign that the conversation about psychedelic drugs and American religion is moving into a new stage. On July 8th that “Old Grey Lady,” the New York Times, published a long and very respectful obituary of Schachter. For this Times reader of the Sixties generation, it was quite surprising that the Times, with its long-history of disdain for the counterculture in general and counterculture religion in particular, would honor a religious innovator whose inspiration was so clearly psychedelic.

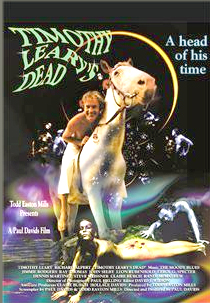

The Times article focused on celebrity/bold-faced names in Sixties culture (it seems that these figures too have also achieved respectability). The obituary noted that Schachter “befriended fellow spiritual seekers like the psychedelic guru Timothy Leary, the Roman Catholic mystic Thomas Merton and Ram Dass (born Richard Alpert) an educator and proponent of hallucinogens and Hinduism.”

It is worth noting that while in 2014 the Times calls Leary “the psychedelic guru,” the 1996 Times obituary for Leary described him as “a dabbler in Eastern mysticism… who had an elegant, happy contempt for authority that made him popular with college audiences decades after the psychedelic experience had expired.”

The Times’ Schachter obituary went on to say that the Rabbi’s “exposure to Eastern religion, medieval Christian mysticism and LSD — he had the first of a handful of hallucinogenic experiences in 1962, under Leary’s tutelage — helped him formulate some of the innovations he brought to contemporary Jewish practice.”

What made Zalman Schachter unusual among the other figures that the Times groups him with, Leary, Alpert/Ram Dass and Thomas Merton, is that Rabbi Zalman was unapologetic about his LSD use and referred to it often in his many books, articles, and interviews. In terms of the relationship between hallucinogens and religious experience, rather than lump all of these “spiritual seekers” together as the Times obituary did, I would make some important distinctions.

In the mid-1960s Thomas Merton, who considered Zalman Schachter a close friend, was skeptical about the “religious value” of hallucinogens, while Schachter was very enthusiastic about it. These two spiritual seekers wrote to each other, and to others, about this question:

A selection from a December 1965 letter in Thomas Merton, in The Hidden Ground of Love:

I know my friend Zalman Schachter is quite enthusiastic about psychedelics. I of course cannot judge, never having had anything to do with them. However my impression is that they are probably not all they are cracked up to be. Theologically I suspect that the trouble with psychedelics is that we want to have interior experiences entirely on our own terms. This introduces an element of constraint and makes the freedom of pure grace impossible. Hence, religiously, I would say their value was pretty low. However, regarded merely psychologically, I am sure they have considerable interest.

And it was as psychologists that Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert first experimented with LSD, which had been developed in a Swiss laboratory in the early 1940s.

Long before Leary and Alpert were at Harvard, they had turned away from their respective Catholic and Jewish family traditions. Leary, the perpetual gadfly and provocateur, had little use for any form of organized religion, but Alpert, to the dismay of many of his colleagues in psychology, turned eastward, to India.

As journalist Sean Gibby noted in Slate:

Unsatisfied by that research, Alpert then traveled to India where he met a man, Neem Karoli Baba, who would become his Hindu guru. Alpert stayed on to study Hinduism with this master, was renamed Ram Dass, and subsequently came back to the States to spread word of new techniques for spiritual practice based on yoga and meditation.

But Alpert/Ram Dass, once he had moved on to Hindu practices and then published the immensely popular book Be Here Now, did not often refer to his LSD use. In that way, he was like the Western Buddhist teachers of the sixties and seventies (many of whom were Ram Dass’ friends and colleagues) for whom the mention of earlier use of psychotropic drugs was considered a liability. And the histories, both academic and popular, of Buddhism in America, are also reticent about mentioning drug use, often burying its mention in the back of the book.

More upfront and honest was poet Gary Snyder, who wrote in the early seventies that there was a direct connection between LSD and the emergence of Buddhism in America: “In several American cities traditional meditation halls of both Rinzai and Soto are flourishing. Many of the newcomers come turned to traditional meditation after initial acid experience. The two types of experience seem to inform each other.”

Schachter, in contrast to Ram Dass and American Buddhist teachers, highlighted the psychedelic experience in his accounts of his spiritual development, often using the phrase: “the sacramental value of lysergic acid.”

As Gary Laderman wrote in his article for the online website Frequencies:

In the late 1960s and through the 1970s, LSD was, for many, a potent manufactured sacrament that unlocked the doors of perception in an American culture imprisoned by theological conformity, blew open the boundaries of religious experience hemmed in by doctrine and narrow ideas about social propriety, and legitimated popular cultural transformations that idealized notions of inner truth, self-seeking personal illumination, and consciousness expansion. In other words, experiences with LSD and the publicity surrounding them gave shape and content to modern understandings of spirituality.

When Rabbi Zalman “came out” about his use of LSD, he did so in his usual provocative fashion. In 1966, he mentioned it in an article in Commentary Magazine (which even in the mid-sixties was quite conservative, although not as conservative as it would become in the eighties and nineties when it moved to the right of Ronald Reagan).

When asked to contribute to a special Commentary Magazine colloquium on “the state of Jewish belief,” Schachter wrote:

The most serious challenges to Judaism posed by modern thought and experience are to me game theory and psychedelic experience. Once I realize the game structure of my commitments, once I see how all my theologizing is just an elaborate death struggle between my soul and the God within her, or when I can undergo the deepest cosmic experience via some minuscule quantity of organic alkaloids or LSD, then the whole validity of my ontological assertions is in doubt. But game theory works the other way too. God too is playing a game of hide-and-seek with himself and me. The psychedelic experience can be not only a challenge, but also a support of my faith. After seeing what really happens at the point where all is one and where God-immanent surprises God-transcendent and they merge in cosmic laughter, I can also see Judaism in a new and amazing light.

From today’s vantage point, the other responses to Commentary‘s colloquium are dry as dust. Rabbi Schachter’s comment is virtually the only one that still speaks to young people.

Reflecting on his first acid trip many years later, Schachter said:

“I realized that all forms of religion are masks that the divine wears to communicate with us. Behind all religions there’s a reality, and this reality wears whatever clothes it needs to speak to a particular people.”

LSD experimentation led some thinkers to adopt a “perennial philosophy” view of the world’s varied religious systems. The most influential among them was Aldous Huxley, who wrote in The Doors of Perception that LSD produced “sacramental visions.”

In contrast to Huxley and many others, Schachter did not go on to reject particularistic forms of religious expression, but sought to change Judaism from within, to make its religious practices more open and attuned to the practices of other religions. And conceptualizing Judaism in the light of his psychedelic experience did not lead Schachter to a rejection of Jewish religiosity but rather, to a redefinition and reformulation of Jewish practices. As he wrote in his Commentary essay: “The psychedelic experience can be not only a challenge, but also a support of my faith.”

In the year of his coming out about his use of hallucinogens, 1966, Schachter gave a lecture to Rabbis and Jewish educators on LSD and the ideas of the Baal Shem Tov, the founder of Hasidim.

In the subsequent half century Schachter became, as the Times correctly notes “the spiritual father of the Jewish Renewal movement.”

His innovations have influenced virtually all of the Jewish denominations. His influences include the rabbinic ordination of women, full participation of women in prayer, creating the “rainbow tallit” that one sees at many Conservative and Reform synagogues, a full acceptance of gay and lesbian lifestyles (both for the laity and clergy), a renewal of interest in ecstatic practices, and incorporating meditation techniques in Jewish ritual practices.

These innovations resonated with American Jews in unexpected ways and to an unforeseen degree. Schachter’s Jewish Renewal still remains small in comparison to the larger Jewish denominations, but its influence it wide. And many of those influenced would be quite surprised to read that in a way, it started with LSD.

But Schachter seemed to have no anxiety about such reactions. A half-century after his first acid trip, Schachter asked writer Sara Davidson (author of Loose Change: Three Women of the Sixties) to collaborate with him on The December Project—a book that would sum up of his life and work.

In that book, published this year only a few weeks before Schachter’s death last month at the age of 89, he reflected on his early experiences among the Lubavitcher Hasidim, with whom he was affiliated in his twenties and thirties. He told Davidson that “When you are in the Orthodox world, you see everything through their frame. But psychedelics had removed that frame. I could take on many points of view, appreciate many different religions and ways of dealing with consciousness.”

“Removing the frame” through the ingestion of hallucinogens was of course, not a new idea cooked up in the sixties. Ecstatic practices, including drug use, are part of the history of culture and religion. Some religious teachers have sanctioned such practices, others have warned their followers against them. And yet others have been ambivalent about such aids to insight. My colleague Lila Porterfield reminded me that an insightful evocation of these responses may be found in Carlos Castenada’s Tales of Power.

Castenada, who has ingested hallucinogenic plants at the urging of his teacher, Don Juan, asks his teacher:

— “Why did you make me take those power plants so many times?”

— Don Juan laughed and mumbled “Because you’re dumb.”

— “I beg your pardon?”

— “You’re rather slow and there was no other way to jolt you.”

Zalman Schachter had been jolted when young, lived to a very productive old age, and wasn’t at all embarrassed by the possibility that we might think him to be “slow.”

And he used his transformation to transform many others, including some Rabbis.

Shalom Goldman is a professor of Religion and Middle Eastern Studies at Duke University. His most recent book is Zeal for Zion: Christians, Jews, and the Idea of the Promised Land (UNC Press, January, 2010).