Luís León

The horrific events in Charleston recently have prompted a robust and much needed conversation on race and the privileges and disadvantages that adhere to it. While conceding that racism continues through individual animus, the political right advances the mythology that institutional racism has ceased, ignoring social inequities such as economic disparity, educational opportunity, incarceration rates, and even life expectancy. Hence, the fantasy that institutional racism is over belies reality, particularly as that reality is crystallized and expressed in the Aspen Institute’s definition: “Institutional racism refers to the policies and practices within and across institutions that, intentionally or not, produce outcomes that chronically favor, or put a racial group at a disadvantage.”

Disney’s new film puts human faces on this definition.

I was hesitant to watch McFarland, USA (directed by Niki Caro, released February 2015). I expected a Kevin Costner as white-man hero fantasy along the lines of Dances with Wolves, wherein Costner becomes a better Indian than the Lakota, whilst living among them. In this regard, to a certain extent, McFarland didn’t disappoint. However, for better or worse the film is mostly based on a true story. The details on how the film differs from the actual events are slight, and do not affect the story in a significant way.

In the film Costner plays Jim White, a high school football coach and physical education teacher who moves his family (wife and two teenage daughters) to the town of McFarland, a rural, backwater farm town located in California’s agricultural valley, not far from Delano, where Cesar Chavez started his movement among farmworkers. At first, White is a reluctant hero who has been fired from a number of jobs because of his explosive temper. McFarland is his last resort and he is counting the days until he can move out of the city and into a better job. In the actual story, White willingly moved to McFarland right after graduating from college in 1964 to teach and coach at the Junior High School there. The change in this detail makes for a better fish-out-of-water narrative frame.

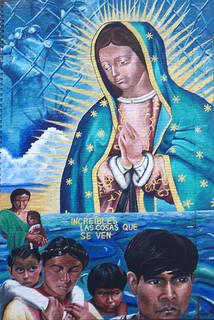

While the film is a drama and not a documentary, it is important as a document of the radical inequalities that rent the fabric of American social and economic life. Families in McFarland are predominantly Mexican and Mexican American farmworkers who live well below the national poverty line and have little access to resources. Yet, they have each other, community cohesion, strong work ethic, and an abiding faith. While the film never shows any of them in church, they live in a sacred communion; the city is their sacred place, their church. Indeed, as the White family enters McFarland, they are greeted by a mural of Our Lady of Guadalupe painted on the side of a store. The image is framed in a medium shot held for several seconds establishing her importance, vigilantly watching over her people.

When the Whites enters their modest stucco home they notice another mural painted prominently on the wall in the front room. It is about a six-foot painting of a Mexican maiden, her hair braided into two ponytails and draped in front of her shoulders. She is set against a backdrop of white lilies that surround her entire body. On a crescent-shaped tray she holds a bounty of green vegetation, mostly lettuce. Her feet are flanked by giant avocadoes. No doubt the vegetables and fruit reference the harvest that the town’s inhabitants work to produce, served on a tray in the shape of a crescent moon is a reference to the Aztec moon goddess, Coyolxauhqui. Its no coincidence that Mexico’s most revered symbol, Our Lady of Guadalupe, also stands on a crescent moon as she is also a composite of referents from colonial Spanish Catholicism and Aztec religion, particularly the amalgam of mother deities referred to as Tonatzin, or “Our Mother.” In addition to recalling Guadalupe sporting a full body halo, the image also recalls the Aztec goddess of Xochiquetzal whose province was fertility, vegetation, and flowers. The lilies in particular refer to Chalchiuhtlicue, an Aztec goddess of water who is typically pictured with lilies. She brings transformation and change. Originally intending to paint over her, she becomes a cherished member of the family.

The remainder of the story is a typical sports film with a David versus Goliath plot. What is remarkable, however, is the enormity of David’s disadvantage. White soon takes note of the farmworker boys’ capacity to run. Many of them rise at dawn to help their families in the picking fields for several hours before running (literally in some cases) to school. After classes they run back to the fields to continue the excruciatingly painful physical labor. They then run back to their crowded impoverished homes to rest briefly before starting the routine all over again. This is the reality of the story: the super exploitation of farm workers who are unable to rise out of their marginalization because they are stuck in a cycle of oppression. When coach White decides to start the cross country team he takes note of the boys’ worn sneakers, asking: “are those the best running shoes you have?” One answers: “These are our best running shoes, our best school shoes, our best church shoes,” in short, their only shoes. Coach White buys them running shoes himself.

The poverty of the McFarland boys is again brought into sharp relief during their first meet in Palo Alto, California, competing against the richest schools in the state whose runners sport impressive uniforms and expensive shoes and bring teams of skilled coaches. The rich white kids mock the McFarland team: “Bet they can’t run without a cop behind them,” says one, “or a Taco Bell in front of them,” adds another. When discussing affirmative action in her 2013 memoir, U.S Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who was Bronx-born of Puerto Rican descent, describes the need to “create the conditions whereby students from disadvantaged backgrounds could be brought to the starting line of a race many were unaware was even being run.” That metaphor reaches full meaning in this film.

The story exhibits typical tropes: tragedy and misfortune overcome; a recalcitrant runner who becomes the star; an uncooperative and incredulous community who come to rally behind the team, taking great pride in the effort. One of the town’s matriarchs, Señora Díaz, mother of three of the runners, played by Diana Maria Riva, fundraises for the team, at one point bringing the community together to make tamales for sale (in real life she once produced two hundred dozen tamales, 2,400!). The authority of the women in the town and film, the matriarchy, is brought fully to bear when Señora Díaz insists that Coach White give his daughter a quinceañera to celebrate her fifteenth birthday. In a delightful scene, Coach White meets some of the fathers and sons in his backyard and begins to prepare for the festivities by arranging the furniture. One of the men advises him to wait explaining, “We’re not the chiefs, we’re the Indians.” On that note dozens of mothers and daughters begin to arrive carrying large trays of food and boxes of decorations. They instruct the men on how to arrange the space. The Whites become part of the town communion.

The team gets better. They begin to win meets. The entire town is exhilarated. On the day of the state championship the owner of the town’s general store and sacred center, Sammy Rosaldo, played by Danny Mora, closes the store for the first time in twenty-five years. Signs supporting the team are displayed throughout the town. The rickety school bus that transports the players to the meet leads a caravan of townsfolk who make the drive to support the team. Spoiler alert: the meet is very close and the shared anxiety of the town and team while they await the results serves to reinforce their bond. Finally, the announcement: McFarland wins! The McFarland fans erupt in jubilation and ecstasy. The snotty rich white kids get their comeuppance. Finally, something to make the town proud. The school won the California state championship first in 1987, and then again in 1992, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1999, 2000 and 2001. Many of the runners went on to college and returned to McFarland to work in its schools (their biographies are available online).

The moral of the story is multiple: believe in yourself; hard work pays off; triumph of the will, and so forth. But I see another teaching: the sacred power of community and the profanity of individualism and isolation. In triumph or tragedy, whether suffering or celebrating, life’s varied experiences are best experienced in community. The film reminds viewers of the synecdoche effect: when one part of a close community wins, joy accrues to all.

The mise en scene emphasizes this truth. The use of the single close up shot is used only sparingly. The film consists mostly of medium and wide shots with two or more people in the frame. Most of the close up head shots feature at least a fragment of another person: a shoulder, the back of a head, a hand, a face fragment—the message being that humans are co-constituted. Those rare instances when there is only one person in the frame the shot is wide, displaying scenery: mountains, ocean, town, homes, emphasizing attachment to the environment. Solo, close up shots are used to establish authority, reserved for Coach white and some of the mothers, with one exception. In the film’s first scene, the unruly and disrespectful football player who mouths off to the coach and provokes his ire and the response that gets him fired from the (fictional) Boise Idaho High School (White throws a cleat near him that ricochets off a locker and hits him in the face) is shot using a series of close ups on his face alone.

In a poignant coda to the film, Coach White is offered a position at Palo Alto High School. He and his family decide to turn it down and stay in McFarland. In real life, Jim and Cheryl White still live in McFarland. Certainly this demonstrates that inter-racial cooperation is happening, and even that opportunities for some racial minorities have increased. But that does not negate the reality of marginalization and suffering that attain to millions because of the persistence of institutional racism.

Luís León is Associate Professor of Religion at the University of Denver. His research and teaching focuses on religion and politics in the United States, Latino/a borderland religions, and cultural studies. León’s publications include two books from the University of California Press: Political Spirituality of Cesar Chavez: Crossing Religious Borders (2014), and La Llorona’s Children: Religion, Life, and Death in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands (2004).