Kelly J. Baker and John David Penniman

After Baker’s article on Hell House was published last year, John David Penniman reached out to her on Twitter to talk more about Hell Houses, and they both realized there was so much more to say about this particular phenomenon and the role of terror in Christianity more generally. Over the last year, they’ve discussed where their own fascinations with Hell Houses originate, how fear and terror appear in Baker’s work on American religions and Penniman’s work in early Christianity, and the role of region in Christian terror.

John David Penniman: First a confession (which seems appropriate, given the topic of this conversation).

I’ve followed with great enthusiasm your work on American religion, apocalypticism, and that special breed of Christianity found in the American southland. The autumnal tradition in the Bible Belt of church-sponsored “Christian haunted houses,” where salvation is delivered through terror, seems to gather together many of your research interests. So I’m really excited to talk to you about Hell Houses. I’ve had a long-standing, morbid curiosity about this phenomenon–derived primarily from growing up in east Tennessee, but also from my own work now as a historian of Christianity.

You mention that you have never been to a Hell House in person. When did you first encounter this phenomenon? Were you aware of it growing up?

Kelly Baker: I grew up in rural north Florida, and I first encountered Judgement Houses (the tamer siblings of Hell Houses) in high school. Many of the youth groups from local churches would bus teenagers to churches in nearby Dothan, Alabama. There was a certain excitement about going to Judgement Houses. While ministers, youth group leaders, and parents hoped to scare the hell out of teens, attendees were mostly excited about the salacious scenes of sin that they were able to watch. Judgement Houses offered up horrors that teens wanted to consume under the scaffolding of preventing damnation. Religious horror appeared more acceptable than secular versions.

My sophomore year of high school I asked my mom if I could caravan to a Judgement House with all the other kids I knew were attending. I thought she might find the ministry appealing, and I would get to go to a haunted house, even if it was a Christian version of one. I was a horror movie buff throughout high school. My mother, on the other hand, stopped watching horror movies in 1968 after she watched Night of the Living Dead at a drive-in. She was aghast at the idea of Judgement Houses much less me attending one. However, she let me throw a costume party for Halloween that same year, and she drove my friends and I out to Bellamy Bridge to look for the local ghost.

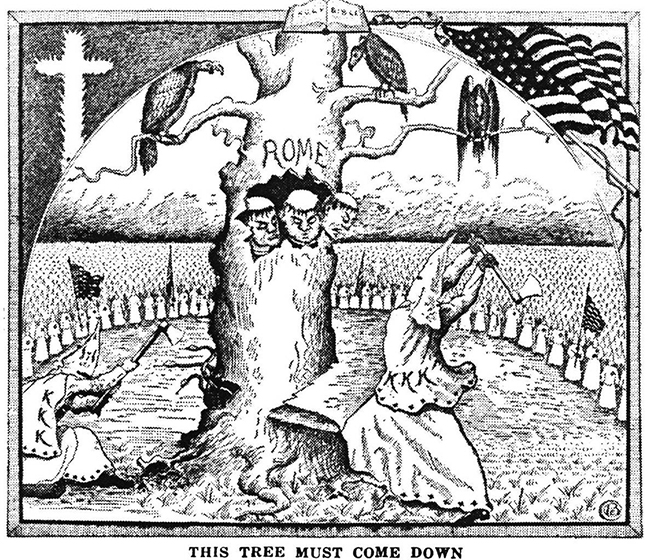

The combination of haunted house and Christianity, horror and religiosity, piqued my curiosity (and I wrote about Hell Houses last year). After years of living in the Bible Belt and hearing continual threats of my own damnation, Hell Houses seemed like a natural extension of the narratives of sin and punishment; they were a logical conclusion to a familiar theology. As a scholar, I’ve wanted to comprehend how terror, horror, and Christianity work together in white supremacist theology of the Klan, the doomsday theologies of evangelicals, and fictional zombie apocalypses.

When did you first encounter Hell Houses?

JDP: I first encountered the Judgement House phenomenon when I was in 8th grade. My family had recently moved from a suburb of Washington D.C. to a small town outside of Knoxville called Oak Ridge (of Manhattan Project fame). I hadn’t been raised in a religious household. There are some deep Irish-Catholic roots on my mom’s side, but this was not a major part of my upbringing. I was not at all prepared for how saturated with religion my life in Tennessee would become. My one and only trip to a Judgment House–now over 20 years ago–was like stepping through the looking-glass. A girl I liked invited me to check out a “haunted house” with her. There were two red flags right away: 1) it was in a vacant department store in the local mall and 2) it was hosted by a church. These did not register with me at the time. I had no idea what I was signing up to do.

In theory, Judgment Houses are premised on the basic evangelical narrative arc of purity, its corruption, and then either a dramatic redemption or terrible condemnation. In practice, my House was mostly episodic, distilling the complexity of teenage life into a series of impressionistic caricatures: a naive group of children dabbled in the occult by playing with a Ouija board; an unwed couple got a little handsy while Boyz II Men played in the background; a goth-kid with a chain wallet smoked weed; and, most vividly, the two climactic scenes representing characters you mentioned in your essay: the “abortion girl” and the “suicide girl.” Both died. In the next room, they were in hell where death metal was blaring out of large speakers suspended from the ceiling. (Judgement Houses are not known for their subtlety with metaphors. Jeff Sharlet has also explored this point in great detail.)

What made hell so hellish was the sensory overload: the kids were thrashing around in locked cages, screaming, strobe lights flashing, all the while surrounded by demons who taunted and tormented the damned. The fate of these two characters offered a fairly straightforward and Dantean lesson: sin issues from the body, and so it is upon the body that its wages are delivered. The gendering of the wages of sin did not occur to me until much later. But you are absolutely correct: the primary bodies being judged in Judgement Houses belong to women. In the final room, my name was displayed on a TV set along with the names of those in my group. I think it was supposed to be an obituary? At any rate, the guide told us we had to make a choice: the door on the left would take us to heaven, the one on the right to hell. In retrospect, of course I wish I had chosen hell–I later heard a rumor that those who picked hell were given fruit punch and cookies. Opting for heaven, my reward was to sit at a table with one of the deacons of the church. He thumbed clumsily through his Bible, reading a few passages from the Gospel of John. A week later, a Bible showed up on the stoop of my family’s house with an invitation to attend the hosting church. As I think back on the experience, I am struck by the fact that Jesus was nowhere to be found inside the Judgment House.

Since we are both historians of Christianity, I am curious how you think about this phenomenon within the broader traditions of the religion. The connection between terror and salvation is an obvious starting point, but I am wondering what analogs you see elsewhere in Christianity?

KB: I hadn’t really thought of my work as an exploration of terror and salvation until you placed the terms side-by-side, but those themes tend to dominate my research and writing. Strange. I’ve spent years trying to figure out how religions inform and create systems of horror and terror. Not in the naive “religion turns bad” way, but rather to examine the darker side of American

religions to see what happens if we pay attention to how religious movements employ fear, violence, and harm to achieve their this and otherworldly goals. This is not entirely popular with other scholars of religions in America or historians of Christianity. That terror can become a method for salvation seems obvious to me. A quick glance at the world around us suggests that not only Christians employ violent and terrible means to achieve their goals.

Yet, there’s still a hesitation about how religion is implicated in terror and hatred. For better or worse, the general public (and scholars) still imagine religion to solely be a force of good in the world. Religion is no longer religion when folks judge it to be bad. When I was writing my dissertation and then book on the Klan, a number of scholars insisted the Klan could not be religious, much less Christian, because they were a hate group. Hate somehow negated religion. They were supposed to be opposed, right? There are still scholars of Christianity and American religions that assume religion can only be associated with movements, peoples, and ideas understood as “good.” What I wanted to show was that the Klan was Christian and racist simultaneously. Theology justified racial terrorism. Racism relied on a particular imagining of white Protestant Christianity.

Even in movements that aren’t explicitly violent, salvation requires terror. Tim LaHaye, the co-author of Left Behind series and a founder of the Moral Majority, spent most of his life prophesying the end of the world and the horrors of Tribulation. In particular, the Left Behind books dwell on the violence, torture, and bodily degradation of those who did not believe in the proper ways. Those who lack salvation face plagues of locusts, the Anti-Christ, the Mark of the Beast, global cataclysm, and then, eternal damnation. The horror of this fate is supposed to motivate readers to adopt LaHaye’s brand of doomsday theology, premillennial dispensationalism, which proposes that the world is an increasingly sinful one beyond saving. Your only hope to escape the world’s destruction is accepting Jesus as your Lord and Savior. You should also only understand theology the way LaHaye instructed you to. (LaHaye died in July.)

This is the long way to say that the analogs are everywhere. I often come back to the first lines of Edward Ingebretsen’s book, At Stake: “Be not afraid.” He’s referring to the moment in the Gospel of Luke, in which the angel tells Mary to not be afraid. What Ingebretsen points out is that fear and terror are essential to religious movements. Saying, “do not be afraid” is recognition that there is something to be afraid of.

Where do you see examples of this gospel of terror? What do you think they point us to?

JDP: I am so glad you mentioned that passage from the Gospel of Luke. Every so often, a picture will pop up on my social media feed that says something like: “The phrase ‘Do Not Be Afraid’ is written 365 times in the Bible. This is a daily reminder from God to be fearless.” The paradox of this sentiment, I think, is how it indicates that the default Christian worldview is not, in fact, one of fearlessness. Rather, it is one of profound longing for relief from the terrors and vulnerabilities within which our daily lives are hemmed. That’s the power of how the axiom functions in Luke’s nativity story. In the midst of the inescapable loss, decay, and death faced by Mary, the shepherds, and the rest of the dramatis personae, a celestial being appears and says: “Hey, hold up, I’ve got some good news.” Who doesn’t long for that kind of interruption? But the angel’s greeting speaks more to a Christian emphasis on life’s precariousness than it does to any kind of fearlessness. This side of death, salvation can only be in the hoping for relief, not the relief itself.

Though I’ve never thought about early Christianity in quite this way, the connection between faith and fear, terror and salvation is all over the place. In the canonical accounts, the life of Jesus is noticeably set within a landscape of unsettling and paralyzing horror. We are told that King Herod ordered the slaughter of all children two years old or younger, a massacre of unspeakable savagery; Jesus tells his followers to leave the bodies of the dead wherever they fall—which would be catastrophic if fundamentalists ever took it literally as a social ethic; in one account of Jesus’s death, when he breathes his last breath, graves yawn open and corpses stroll into Jerusalem; and at the end of Mark’s gospel, even though the mysterious figure in the tomb tells them not to be afraid, the women flee the scene in terror and refuse to speak a word of what just happened. It was later editors of the biblical text who smoothed out this rough and unsettling conclusion to the life of Jesus.

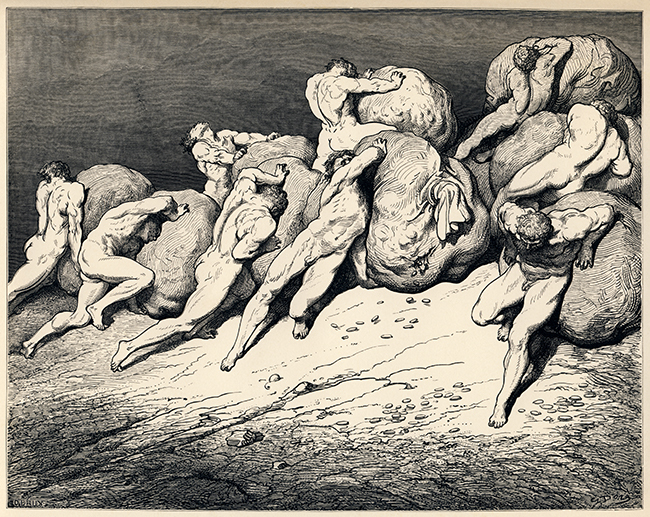

What I’m trying to say is that fear was a powerful goad prodding the Christian imagination from the very beginning. The ancient sources do little to assuage anxieties about contamination, disease, loss, and death. Cyprian of Carthage tells the story of a little girl whose nanny carelessly gave her food offered at a “pagan” sacrifice. When the girl’s parents later take her to church and the Eucharist touches her mouth, the demonic pollution inside her belly causes the child to vomit up the body and blood of Jesus. In a sermon on the beheaded martyrs Juventinus and Maximinus, John Chrysostom describes how the two men were buried together, their cradling hands folded into a reliquary for the severed skulls. Chrysostom says that the numinous power of these headless saints attracted throngs of people who would travel to the tomb just to tremble at the sight of the martyrs’s bones. (If, as tradition holds, martyrs carry their wounds into heaven like military honors, Juventinus and Maximinus will make paradise a rather macabre affair.) And in the ascetic literature, monks are often afflicted with terrifying sensory events that test their piety and resolve. The Greek word for such events (φαντασία) is where we get the English “fantasy” and “phantasm,” suggesting that faith and fear often cohabitate in the same shadowy pocket of our psyche. And what is the Judgment House if not a conjuring of phantasms?

So in the wide arc of the history of Christianity, deliverance from fear is mostly deferred. Deliverance is the carrot on a stick, dangling tantalizingly close but ever out of reach. Fear is the goad that pokes you forward. Christians have wanted to hold onto fear because it is pregnant with pedagogical value. Fear has been used to instruct the faithful for centuries, providing a powerful idiom for communicating the crucial lessons of faith with the greatest affective impact. Put another way: if you want to understand the values of a particular Christian community, look first at what they fear, listen to how they describe that fear, and watch how they live in response to that fear. From this vantage, the Judgement House tradition is situated within a much broader legacy of Christianity’s relationship to terror.

And of course the tradition makes me think of Flannery O’Connor’s famous description of the South as “Christ-haunted.” Why do you think the region is so attuned to this combination of fear and faith, terror and salvation? What makes it more prone to enact that relationship in dramatic fashion?

KB: The South has always seemed seriously spooky to me. The rural cemeteries lining long stretches of road with faded plastic flowers and cement angels. The abandoned houses that almost proudly show their wear and dare you to enter. The trees and bridges that once held the ropes hung around the necks black men by white men while white crowds watched on. The ghostly Klansmen who threatened to march in town and burned crosses late at night. The stories passed down to me from my grandparents about all the people who died from their own mistakes, natural disasters, or the more mundane things that we imagine won’t kill us. One small mistake, they seemed to note, and your life could be over. We’re always just a foot away from the grave. We’re always one small step from salvation or damnation. Those are feelings that I’ve never quite been able to shake.

1884 lithograph of a cotton plantation on the Mississippi. Image available via Wikimedia Commons.

The history of the South, like the history of so many other places in the U.S., is drenched in blood, guts, and loss. I had this book in middle school about the famous ghosts that could be found all over the South. Quite a few of the ghosts were enslaved people most often killed by white slave owners. Other ghosts were prisoners murdered by mobs before a trial could determine their guilt. For awhile, I imagined if I looked at my surroundings just right, with a tilt of my head and a squint of my eye, maybe I could see all the dead who continued to haunt us. The landscape was full of ghosts who we could never quite see. These ghosts never seemed that scary; they were the reminders of how dangerous our capacities for violence and hate can be. But, the people who ended their lives were truly frightening. For me, the South has always been haunted, but it took me awhile to realize that this region of my birth, where I chose to live now, was also Christ-haunted.

The churches I attended and abandoned found fear, no, terror, to be a powerful motivator. Jesus might bring you redemption, but fear from hell was what would bring you to Jesus. Redemptive love was too soft a message compared to brimstone, fire, and wiles of Satan. Preachers would spend more time cataloging the punishment for sins rather than encouraging the congregation to not be sinful. Sin was something we were supposed to fear, even as it tempted and tantalized us. (Hell Houses materialize this conflict in every scene, prop, and scripted line.)

Ghosts were tame outcome of a life ended compared to an afterlife spent in agony and torture. I’ve spent much of my life wrestling with that particular strand of Southern Christianity that paints a stark portrait of your options: find and accept Jesus or burn in hell. Be saved or be punished. (Or possibly be punished to be saved.) Either way, the decision rests with you. You are supposed to decide, and then, live with your decision. Judging other people’s decisions seems almost required. This approach to the world that divides everyone into the tidy categories of saint or sinner doesn’t remain within churches but bleeds over into the culture of the South. It still resonates in my bones, even as I avidly try to work against it. The South is about judgment, but I still find glimmers of redemption too. Those glimmers are what keep me here.

I’ll throw the question back to you. Why do you think the South is Christ-haunted? What makes this region combine fear and faith so avidly?

JDP: Yes! The roads. The southern roads. That’s the key, I think. It always seems to me that O’Connor’s famous phrase is best experienced first hand, driving through the back roads of the south. Recall that ominous final drive in “A Good Man is Hard to Find.” Will this road lead to an encounter with grace? Or will it led to the horror of our undoing? O’Connor’s brilliance–and I think this gets at something essential about the Christ-hauntedness of the south–is in the notion that the encounter with grace and the horror of our undoing often occur in the same moment.

There was a country highway we used to drive regularly from Oak Ridge to Knoxville. We were close enough to the Smokies that the road was usually shrouded in mist. Tiny Baptist churches and rundown auto shops marked every mile. My father would laugh out loud every time we drove past the makeshift sign that announced: “Jesus Saves. We Sharpen Chainsaws.” And kudzu reached its tentacles out of the treeline in every direction, fingering its way over abandoned cars, smothering the entire landscape like a pillow pushed down on a sleeping face. Driving that road, there is a sensation of intimate familiarity and yet profound otherness. The landscape is slowly devouring itself. But Jesus still saves.

I think there’s something similar at work in the Judgment House. I walked through this awful tableau of moralizing and damnation, an experience of total otherness, but then this elderly deacon nervously talked to me about how much God loves me. It was confusing, unsettling, offensive, and also kind of enthralling. When mixed together, faith and fear produce a unique kind of dramatic tension. The church could have simply rented the space at the mall and had the deacons tell passersby that God loves them. But it opted instead for this elaborate production. It wanted to tell a story, to place each person within a very specific plot. And fear was that story’s hook. It occurs to me that this hook sits at the core of my experience of Christianity in the south: faith was something that had to be felt. And fear was often the means to get there.

Maybe the combination of intimacy and otherness is another way of talking about faith and terror, another way of getting at the particular Christ-hauntedness of the south? The comforts of faith in the south, as I encountered them as a teenager, were usually the second part of a two-act play that began with scaring yourself shitless. Who doesn’t want the pleasure of a weekly potluck among kindhearted folk? But there’s no sampling the sweet potato casserole without first passing through apocalypse and hellfire and altar calls.

I know you said that you’d probably never enter a Judgment House after avoiding them all these years. I’ve wondered the same thing for myself. I very much agree that the theology–and especially the gendered morality–of this tradition is terribly toxic. Yet our conversation has also renewed my curiosity as a historian and a student of religion. So I guess I have you to thank for that!

KB: You’re right. I won’t be attending any Hell Houses in the near future! And yet, after our conversation, I find myself even more curious about terrifying manifestations of Christianity. Thank you for helping me think about Hell Houses, and my own research, in new yet different ways and for sharing your thoughts and analysis too. This was fun (when it wasn’t scary).

Kelly J. Baker is a freelance writer with a Religious Studies PhD who covers higher education, gender, labor, motherhood, American religions, and popular culture. She is the author of Gospel According to the Klan: The KKK’s Appeal to Protestant America (2011) and The Zombies are Coming! (2013). She can be followed @kelly_j_baker.

John David Penniman is an Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at Bucknell University. His research focuses on the development of Christianity within the cultural worlds of ancient Greece and Rome. He teaches courses on the New Testament, early Christianity, the history of western religious thought, and theories of religion, among others. His first book, Raised on Christian Milk: Food and the Formation of the Soul in Early Christianity, is forthcoming from Yale University Press (spring 2017). He can be followed on Twitter @historiographos.