Arthur Remillard

I’m sure that you know the old adage that one should avoid talk of politics and religion in polite conversation. In light of recent events, it’s time to add sports to this list of taboo topics.

When San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick began kneeling during the national anthem, he sparked a heated debate over politics, race, and patriotism in America. Even President Obama has weighed in, assuring that the quarterback is “exercising his constitutional right.” The president then added, “I think there’s a long history of sports figures doing so.”

Indeed, there is.

Many observers have been quick to draw parallels to the 1968 protest of American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the Mexico City Olympics. At the time, these athletes were reviled and harassed. But the image of their raised fists on the medal stand has since become iconic, a portrait of audacity, resilience, and fortitude.

Others have drawn comparisons to the more recent Olympic protest of Ethiopian marathoner Feyisa Lilesa. As Lilesa neared the finish of this year’s 26.2 mile event to claim the silver medal, he raised his arms and crossed his wrists in an X above his head. We soon learned that this gesture was a show of solidarity with the beleaguered Oromo people in his homeland. Last November, thousands of Oromo—Ethiopia’s largest ethnic group—participated in antigovernment protests, a movement that drew a swift and violent response. Human Rights Watch estimates that the government is responsible for hundreds of deaths and thousands of imprisonments. The press in Ethiopia has been silenced and social media has been blocked.

But the #OromoProtests continue. And Lilesa has only made their voices louder.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Lilesa’s story has also been told in close proximity to the protest of Smith and Carlos. It’s an appropriate connection, but ultimately incomplete. Instead, the crossed wrists of Feyisa Lilesa are best understood in relation to the leathery feet of another Ethiopian who also made a unique political statement at the Olympics over fifty years ago.

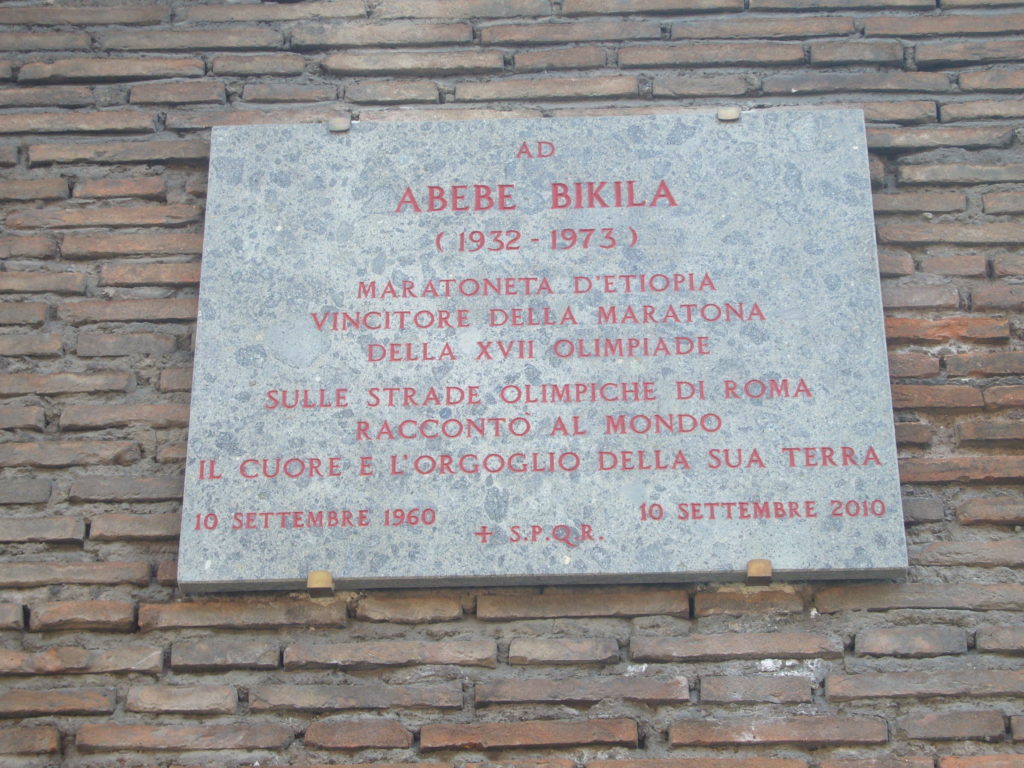

At the starting line of the 1960 Olympic marathon in Rome, Abebe Bikila of Ethiopia was an unknown among distance runners, drawing attention only because of his bare feet. “Oh well, that’s one we can beat,” quipped one Australian runner to his teammates. The snickers silenced once the race began, as Bikila hovered among the lead runners who, one by one, fell off the pace. All the while, the Ethiopian kept gliding effortlessly along the jagged cobblestone streets of Rome. Wider and wider his lead grew until he entered the stadium far ahead of his competitors. A bewildered audience then watched him stretch across the finish line in a world record time of 2:15:16.

Bikila was the first black African to win an Olympic gold, an achievement that was also thick with political irony. The marathon began from the Arch of Constantine, the same place where, in 1935, Mussolini’s troops paraded as they prepared to invade Ethiopia. Additionally, Bikila supposedly made his definitive surge to win the race just past the 24-mile mark. At this spot stood the Obelisk of Axum, a religious relic that was plundered by Italian troops during the Ethiopian campaign.

In a few short hours, Bikila’s barefoot procession did the work of making Ethiopia a place not to be colonized or pitied, but to be respected and admired. “I wanted the world to know that my country, Ethiopia, has always won with determination and heroism,” he announced after the race.

The word “hero” would quickly become inseparable from Bikila’s name. In the Homeric tradition, heroes emerge from the unions of gods and mortals—demigods who occupy the uncomfortable place between eternity and the finite. With this in mind, Socrates liked to think of heroes as being, “speech makers and questioners.” Questioning, of course, is at the core of the Socratic method. To ask the right question is to form a bridge between the truths of eternity and the limited understanding of humankind. Moreover, Socrates indicated that the pursuit of knowledge is animated by a deep love. Thus, philosophy is the love of wisdom.

Heroes, then, ask uncomfortable questions because they have little concern for the world as it is. Their focus is to reshape the world as it ought to be. This, ultimately, is what makes heroes semi-divine, venerated for their passion, courage, and tireless pursuit of justice. In 1960, one barefoot marathoner became a hero when his body did the work of refashioning the world’s perception of Ethiopia. And in 2016, his countryman delivered a new image of Ethiopian heroism with his finish line protest. In both instances, the world witnessed runners who made impassioned speeches with their straining breaths and asked probing questions with their laboring legs all in an effort to broaden our shared humanity.

Arthur Remillard is Associate Professor of Religious Studies at Saint Francis University in Loretto, Pennsylvania. He is author of Southern Civil Religions: Imagining the Good Society in the Post-Reconstruction Era and he is currently working on a book entitled Bodies in Motion: A Religious History of Sports in America.