Rachel Pafe

Ants scurry across a static crucifix as the figure of Jesus Christ surfaces again and again on screen, sandwiched between bowls of blood, a figure masturbating, couples having sex, and conservative Christian groups—all brought together in one film. Jesus Christ makes many appearances in “David Wojnarowicz: Photography & Film,” at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin (February 9, 2019 through May 5, 2019), an exhibition of Wojnarowicz’s film and video works presented as part of a trio of solo exhibitions devoted to AIDS activists. In this exhibition, the artist’s world is often negotiated through a sense of awe at both beauty and cruelty, especially evident in his attitude towards religion. While Wojnarowicz often denounced Christianity and its symbols as synonymous with institutional corruption and prescribed morality, he also used Jesus as a symbol of hope. I will explore his use of Jesus Christ between personal belief and institutional religion, both a symbol hijacked by corrupt powers in the profane world and a vessel of hope for fashioning an ideal world.

David Wojnarowicz (1954 – 1992) was an American artist born and raised in New Jersey in a tumultuous Roman Catholic family. After familial abuse and several foster homes, he became a sex worker in New York in his early teens. When he left this profession a few years later, he started making artwork. He was best known for his aesthetically bright and psychologically uncomfortable paintings, but he also worked with photography, sculpture, film, installation, performance, and writing. Two major themes in many of his works are a sense of injustice and the failure to fit into “normative” American life.

Addressing injustice became especially urgent during the 1980s AIDS crisis. Wojnarowicz watched as friends and lovers died, before he himself eventually succumbed to AIDS at age 37. He participated in activist movements such as ACT UP and his work took on an overtly political tone, although he emphasized that his fury did not just come from the personal position of having AIDS. Rather, his anger was a reaction to a corrupt society in which institutional forces, especially conservative politics and religion, conspired to suppress the racially, sexually, and materially marginalized. In Wojnarowicz’s writing, he often positions “religion” as a political force for making moral judgments that can have lethal consequences, such as the conservative Christian fight against sexual health education at the height of the AIDS crisis.

In the exhibition at KW, Wojnarowicz’s view of religion constantly reaffirms and contradicts itself. Two particular pieces, Phil Zwickler’s Interview with DW surrounding the A.F.A controversy and A Fire in My Belly, show the poles of institutional religion and personal symbol making in Wojnarowicz’s politics.

The first room features a grainy projection of half of Wojnarowicz’s face in the darkness. He speaks about having AIDS while being surrounded by intimate photos showing the death of his close friend, brief lover, and mentor, Peter Hujar. Meanwhile, Phil Zwickler’s Interview with DW surrounding the A.F.A controversy plays on a small television on the nearby table. It is not Wojnarowicz’s work, but a compilation by filmmaker/journalist Phil Zwickler, featuring news footage overlain with audio from Zwickler’s interview with Wojnarowicz. The words of the interview are indiscernible as they are obscured by newsreel clips about the fall of the Berlin wall, which includes black and white footage of John F. Kennedy’s “ich bin ein Berliner” speech, images of post-Berlin wall glee, and various fluff news reports, like one talking about “the dark side of beautiful blondes.”

Zwickler’s interview relates to an incident in 1989, when the founder of the American Family Association (AFA), Methodist minister Donald Wildman, mailed pamphlets to members of congress, news venues, and religious leaders about blasphemous images in an exhibition partially funded by the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). The pamphlet especially focused on Wojnarowicz’s Untitled (Genet) (1979), in which Christ shoots up heroin in a destroyed church next to a haloed image of famed French gay writer Jean Genet. Wojnarowicz sued Donald Wildman on the grounds of misrepresenting his art and eventually won the case.

In 2010, Wojnarowicz’s Christ was attacked again. This time Bill Donohue, president of the Catholic League, and several members of Congress, took issue with the image of a crucifix with ants crawling on it. The image appeared in a clip from the work A Fire in My Belly (1987), which was featured at “Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture” at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. The Smithsonian eventually caved to the demands of this group and took down the work, but the attention from the controversy caused A Fire in My Belly to go viral.

Talking about the particular image of Jesus that the AFA challenged, Wojnarowicz stated,

“I thought about what I had been taught about Jesus Christ when I was young and how he took on the suffering of all people in the world, and I wanted to create a modern image that, if he were alive before me at that time in 1979 when I made this… I wanted to make a model that would show that he would take on the suffering of the vast amounts of addiction that I saw on the streets.”

In this context, Wojnarowicz’s version of Christ highlights the policing of religion in the United States. In general, his work presents two conflicting Christs: one who takes on the suffering of all and one who takes on the suffering of some. Wojnarowicz vehemently argues that conservative Christian groups have hijacked Jesus Christ and have used him as a figure who only takes on the suffering of a select few. He often places this assertion within broader question of who decides the meaning of religious symbols. For example, in a memoir/essay collection entitled Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration, Wojnarowicz wonders, “Do some politicians have a direct communication with god?… Should one person’s interpretation of god determine whether another person lives or dies?” The use of Jesus Christ as a symbol of hope pits a personal belief against institutional power, suggesting that the American struggle with conservative moral values does not stem from religious symbols in and of themselves, but from a particular interpretation of religious symbols by those in positions of power.

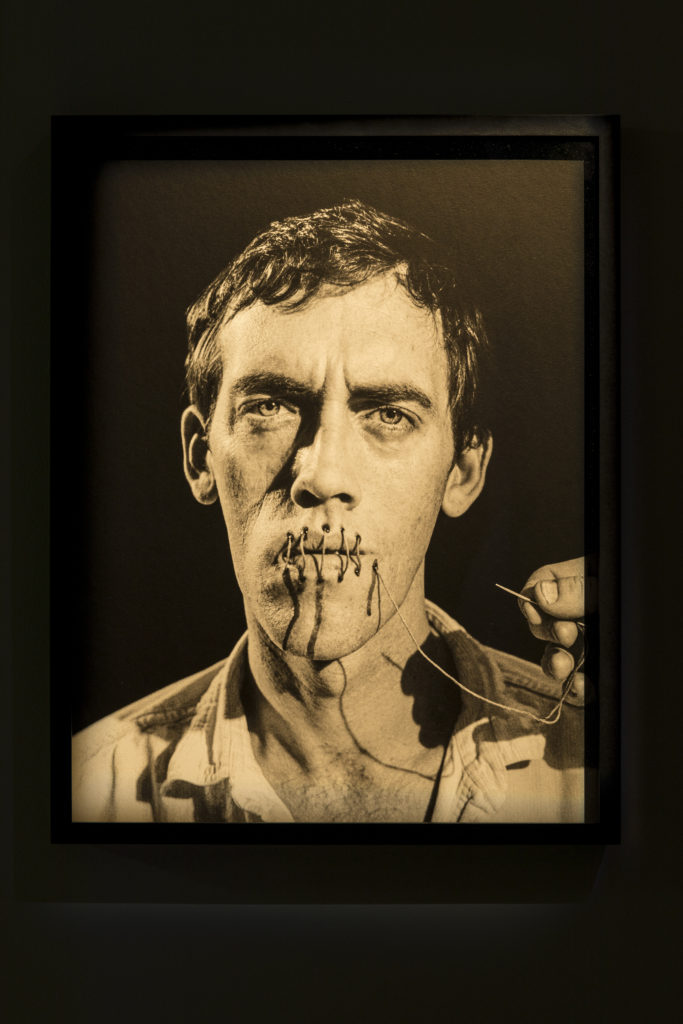

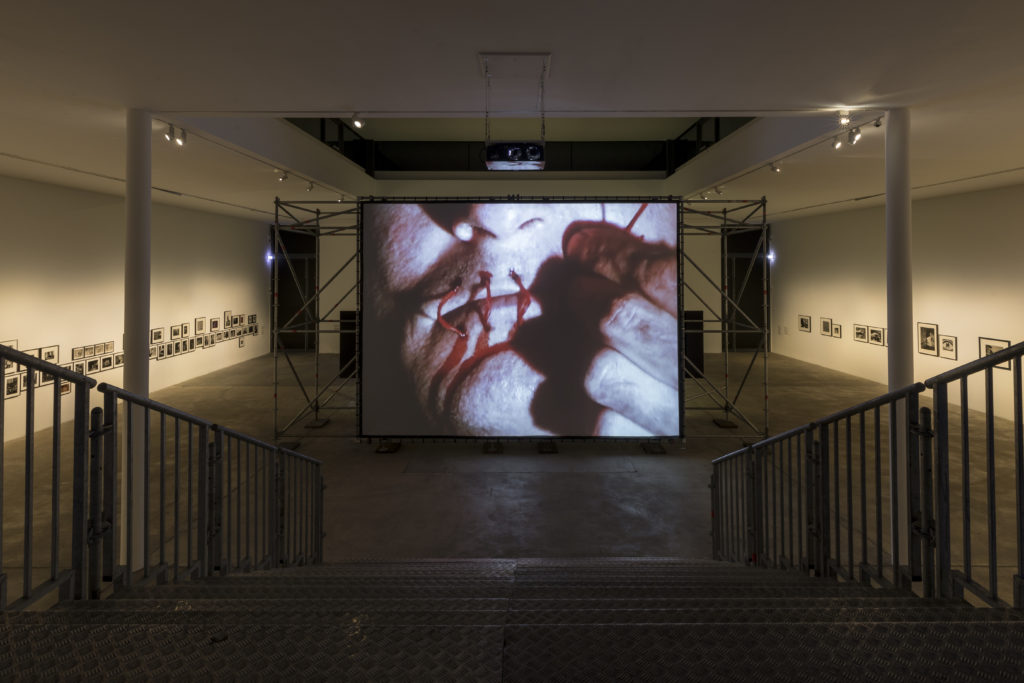

The many dimensions of Wojnarowicz’s Christ continue in the aforementioned A Fire in My Belly, which appears at the end of the KW exhibition. It follows from series of smaller rooms featuring Wojnarowicz’s films and photography. The photos and films in these rooms showcase trashed warehouses as playgrounds, a mouth sewn shut, a snake seductively squeezed between thumb and forefinger, and a wobbly heroin needle. Passing from these rooms into a large room, A Fire in My Belly plays on a huge, floating projector. It is an unfinished super-8 film from 1986-1987, when Wojnarowicz was in Mexico. Wojnarowicz eventually dismantled this film and used it in other works. The KW featured two versions, but I will focus on the seven-minute version, entitled A Fire in My Belly: Excerpt.

The seven-minute excerpt is a series of quick juxtapositions. It starts with quickly turning metal wheels versus slowly plodding, legless beggars, then shots of police officers emptying money from an armored vehicle contrasted with destroyed Mexico City streets and Day of the Dead skeletons. Interspersed in these clips are still shots Wojnarowicz made in his New York studio, all relating to blood, water, and fire.

First, a disembodied hand receives some coins. The next shot features coins falling into a bowl of blood. Then, there is the following sequence of shots: a loaf of bread is stitched together with red thread, bloody lips are stitched shut, and Saint Lucia holding bloody eyes on a platter. Shots of a strobe-lit man undressing and masturbating alternate with hanging slabs of meat and a now-bloody hand receiving coins. A blinking, holographic postcard image of Jesus watches these scenes while visibly in pain as ants scurry across coins, clocks, and a crucifix. At the end, two cupped hands receive water, contrasted with a grave being lovingly washed, followed by burning sculptures of Jesus and a floating eye.

The first Jesus Christ, the holographic postcard, could be a suffering witness. The quick succession of shots makes it seem like he is watching the scenes of violence and inequality with a look of pain, much like the Christ in Untitled (Genet). Here, Christ also seems to be receiving the sins of the powerless, particularly underlined by the many shots of beggars contrasted with police officers—the latter smile nonchalantly as they guard a stash of money.

The second Christ image, the ant-covered crucifix, is quite static and seems less alive than the previous holographic postcard. The crucifix is left alone on gravel, making it appear more dejected than openly in pain. The many coins surrounding the crucifix do nothing to help the situation, while ants crawl across it in untiring motion. Perhaps this suggests that the power of money does nothing to help the teeming masses, who constantly labor to keep society going. Could Christ be left behind in the forward motion of a violent, fast-paced society? He is there to receive sins, but no one regards him.

The theme of the disregarded Christ appears in similar works. In the multimedia film ITSOFOMO (In the Shadow of Forward Motion) (1989), the crucifix is juxtaposed with conservative Christian groups, and a close-up, black and white photo, Untitled (Spirituality) from the Ant Series (1988-1989). Exactly like in A Fire in My Belly: Excerpt, in Untitled (Spirituality) from the Ant Series ants crawl over a dejected and blankly staring Jesus on the crucifix. Similarly, in Untitled (Sex Series for Marion Scemama) (1988-1989), the crucifix appears in a tiny circle on the back of a group of police officers. The images and juxtapositions in A Fire in My Belly: Excerpt are imbedded in Wojnarowicz’s broader approach to religion.

The last Jesus Christ in A Fire in My Belly is actually another work, Portrait of Bishop Landa (1986), a papier-mâché image of a sixteenth century Spanish bishop in Yucatan, who is known for destroying the religion and culture of the natives there. The original piece was meant to reflect on the Church’s use of its power to enact violence on peoples’ culture and religion. Wojnarowicz, however, depicted Landa as Jesus and lit him on fire. The previously mentioned scenes of hand washing, immediately followed by the burning the Christ-like Landa portrait, perhaps signify a ritualistic attempt to cleanse. Wojnarowicz destroys a hijacked understanding of Jesus Christ and seeks to dismantle how we have been trained to see him.

The images of Jesus Christ seem to manifest in different ways: Jesus as witness, Jesus as reject, and Jesus as a hijacked figure. Taken together, they draw out the nuance in the gap between the right to take on a symbol for one’s personal belief versus societally mandated norms that dictate how an image should be used and by whom. Wojnarowicz had no single way of relating to Jesus Christ, but rather used him in ways that reflected Jesus’ tumultuous place in American life, a place where religion is powerfully intertwined with political power. In the struggle to force the government to come to terms with the AIDS crisis, sex education, rampant inequality, and blatant mistreatment of sexual, ethnic and political minorities, the visual symbol is a battleground. Wojnarowicz took an image that has historically been marshaled by those in power and used it to both contain his hope for a better world and decry its place in enacting harm.

Just as his work again provoked controversy in 2010, the issues that Wojnarowicz brings up in the religious dimensions of his work are far from over. They may be more urgent than ever in fact. Exhibiting Wojnarowicz’s work in a glossy museum in Germany risks historicizing it and forgetting that it applies to American issues today. ACT UP protestors at the recent Wojnarowicz 2018 Whitney Museum retrospective came out to say that more must be done in solving the AIDS crisis. (Protestors emphasized the Trump administration’s failure to deal with the AIDS crisis, which has recently morphed into a sketchy medication deal with the pharmaceutical giant Gilead.) This issue is connected to broader issues—the US government’s suppression of LGBTQI rights, climate change denial, a desire to control women’s bodies, limitations on affordable healthcare, and the violence associated with recent immigration policies. Extending beyond the United States, solutions to these issues have been complicated by the global turn toward far-right politics. In this climate, we can look to Wojnarowicz’s work as an example of how to question, reclaim, and combat the images that make up our current reality.

Rachel Pafe is a researcher, writer and freelance editor. She has an MRes in Art: Exhibition Studies from Central Saint Martins and is currently a student in the MA Jewish Studies program at the University of Potsdam. Her research focuses on how contemporary art exhibitions deal with artistic representations of religion. It specifically explores the potentials and pitfalls of using religious structures as metaphors for institutional critique in contemporary art and ways of investigating this through Jewish and interfaith temporal schemas.

All images associated with the KW Institute for Contemporary Art have been used through permissions granted to Rachel Pafe.

Citations for the photo gallery above:

- Andreas Sterzing, Untitled (David + Nest + Globe), New York 1989, photograph, installation view of the exhibition David Wojnarowicz Photography & Film 1978–1992, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, 2019, Courtesy the artist, the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York, photo: Frank Sperling

- Andreas Sterzing, David Wojnarowicz (Silence = Death), New York 1989, photograph, installation view of the exhibition David Wojnarowicz Photography & Film 1978–1992, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, 2019, Courtesy the artist, the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York, photo: Frank Sperling

- David Wojnarowicz, A Fire in My Belly, 1986–1987, Standbild aus Super-8-Film, Installationsansicht in der Ausstellung David Wojnarowicz Photography & Film 1978–1992, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, 2019, Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York, Foto: Frank Sperling

- David Wojnarowicz, A Fire in My Belly, 1986–1987, film still taken from Super-8-Film, installation view of the exhibition David Wojnarowicz Photography & Film 1978–1992, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, 2019, Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York, photo: Frank Sperling

- David Wojnarowicz and Ben Neill, ITSOFOMO – In the Shadow of Forward Motion, 1989/2018, video still taken from VHS transferred to digital video, installation view of the exhibition David Wojnarowicz Photography & Film 1978–1992, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, 2019, Courtesy Marion Scemama, photo: Frank Sperling

- Marion Scemama und David Wojnarowicz, When I Put My Hands on Your Body, 1989, Standbild aus Super-8-Film, Installationsansicht in der Ausstellung David Wojnarowicz Photography & Film 1978–1992, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, 2019, Courtesy Marion Scemama, Foto: Frank Sperling

- David Wojnarowicz and Jesse Hultberg, Beautiful People, 1988, film still taken from16 mm film, installation view of the exhibition David Wojnarowicz Photography & Film 1978–1992, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, 2019, Courtesy Marion Scemama, photo: Frank Sperling