Deepak Sarma

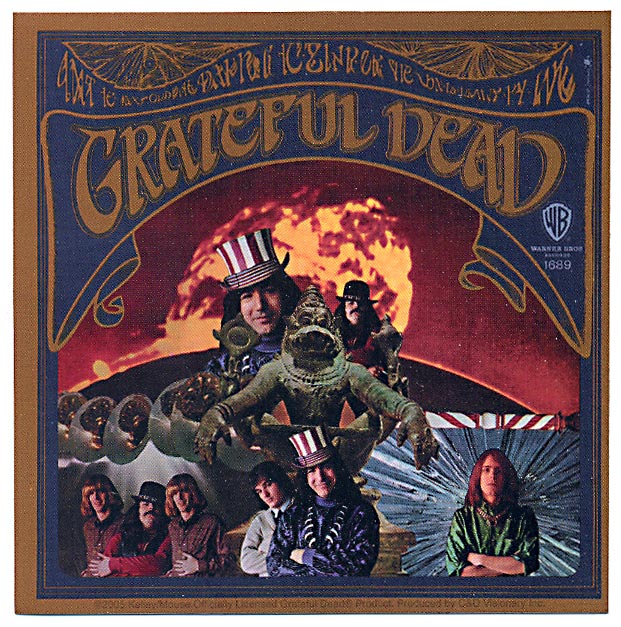

I was casually looking at my old vinyl albums and was startled when I saw a familiar image of Narasimha on the cover, just underneath the picture of the head of Jerry Garcia, the virtuoso singer-songwriter and guitarist of the Grateful Dead. Though I have owned and listened to the album for more than 25 years, I never looked at the album cover with the trained eye of a scholar of South Asia. As per the lyrics of the Grateful Dead’s “Scarlet Begonias,” “Once in a while you can get shown the light, in the strangest of places if you look at it right.”[1]

Some determined detective work uncovered that the image used in the album cover collage is unquestionably a low-angle shot of the 12th century Chola sculpture of Yoga-Narasimha (The Man-Lion form of Visnu), held at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City.[2] The image depicts the Man-Lion avatar of the Hindu god Visnu. The god is depicted with a yoga-band around his legs and is typical of similar images produced during the time period.[3]

Hindus believe that in his fourth avatar (incarnation) the god Visnu takes the form of the Man-Lion Narasimha.[4] He is incarnated in order to kill Hiranyakashipu, who not only wants to destroy Vishnu, but threatens the order and peace of the universe. Hiranyakashipu is believed to have obtained a boon from the God Brahma that he would not die on earth or in space, in fire or in water, neither during the day, or at night, inside, or outside, not by a human, animal, or a god, and finally, and not by an inanimate animate being. With this purported invincibility Hiranyakashipu terrorizes the world. His son Prahlada (who is devoted to Lord Vishnu) refuses to bow down before his father, when demanded to do so. Prahlada tells his father that Vishnu is everywhere. Hiranyakashipu points to a pillar and asks Prahlada if Vishnu could be found within it. When given the affirmative Hiranyakashipu, enraged, strikes the pillar with his sword. From the broken pillar emerges Narasimha. Neither human, nor animal, Narasimha kills Hiranyakashipu at twilight, at the doorsteps of the royal palace, placed upon his lap, and using his nails. This is the god who is depicted in the Nelson-Atkins sculpture and in the collage on the cover of the first Grateful Dead album.

How did this unusual image of this unusual god with such an unusual story end up in a collage on the Grateful Dead’s debut album, which was released by Warner Brothers Records in March 1967? Why was this image was used, who took the photo, and was it significant (at the time of its release) to the members of the Grateful Dead?

To answer this and related questions I needed to do so some more sleuthing. As far as I can tell, there is no scholarly work on the album art of the Grateful Dead’s first album, other than a few references to the lettering and legibility.[5] I’ve discovered two informal blogs in which the Chola image is incorrectly identified as “The Creature from the Black Lagoon” and as “Hanuman.”[6] Correspondence with the Registrar at the Nelson-Atkins, moreover, indicates that the Museum itself has been unaware that their Yoga-Narasimha was used by the Grateful Dead until I informed them at the end of February 2018.[7]

I decided to get in touch with Mike Wilson, the archivist at Warner Brother’s Records.[8] Alas, after looking through the WB archives, Mr. Wilson was not able to offer any remarkable or relevant data.[9] In a phone conversation he did mention that he was not surprised that there were no records of the use of the image since record keeping at that particular time in music history (the mid to late 1960s) was stereotypically lax! He did suggest that I try to interview living members of the band but, alas, I am still pursuing that unreachable lead.

I also looked at the online Grateful Dead Archives held at the University of California at Santa Cruz. The entry for their first album provided no significant insight other than references to the artists who helped put the cover together, namely Alton Kelley, Stanley Mouse, Herb Greene, and Gene Anthony. I wrote to Mouse, Greene, and Anthony, and heard back only from the first two (Alton Kelley, of course, died in 2008). Greene confirmed that Kelley was responsible for the collage and Mouse for the design and lettering.[10]

Kelley and Mouse worked together to create some of the most wildly viewed art of the psychedelic sixties.[11] There is no direct information about what drew Kelley and Mouse to Asian art. In a 2007 interview for the San Francisco Chronicle, however, Kelley said

…we went ahead and looked at American Indian stuff, Chinese stuff, Art Nouveau, Art Deco, Modern, Bauhaus, whatever. We were stunned by what we found and what we were able to do. We had free rein to just go graphically crazy.

Joel Selvin, author of Kelley’s obituary in the San Francisco Chronicle, describes the scope of their creativity:

During the heyday of the Avalon Ballroom, the pair would frequent the public library looking for images they could employ in their poster-making; Edward Curtis photographs of American Indians, illustrations from 19th century novels (the skull and roses was adapted from “The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam”), often laughing so loud at what they found the librarians would ask them to leave.

Given this account, it is plausible that the Nelson-Atkins image of Narasimha was one that they came across randomly (or by reason of their good karma!) at the library and that caught Kelley’s eye.

However this explanation is only somewhat satisfactory. There is indeed a record of a photograph of it being published when Kelley and Mouse were working on the album cover. An image of the sculpture is thus found in Master Bronzes of India, an exhibition catalogue,[12] and a textual reference to it is found in The Nelson Gallery & Atkins Bulletin.[13] The former does indeed include a photograph of the image while the latter does not. There is no record of the Master Bronzes of India being held by the San Francisco public library, though it is possible that Kelley may have come across it in his wanderings around the Bay Area.

Alas, this also is only partially satisfying: the image that was used in the album cover is a low-angle shot while the image found in the Master Bronzes book is not. Could it be that Kelley found it in a magazine? Or, as Mouse stated in an electronic correspondence with me “It was an Alton Kelley collage and he probably saw it in a National Geographic magazine cut out”! There are no records, however, of a photograph of the image being used by National Geographic after the image was purchased from J. J. Klejman by the Nelson-Atkins in 1963.

These speculations, though, do not take into consideration the possibility that any museum visitor with a camera could take a photograph of an object on display without the museum, or anyone else, coming to know about it. This seems to be the most likely scenario since the image used by Kelley (or perhaps even taken by Kelley) is, to reiterate, a low-angle shot. Such an orientation is unusual and suggests a patron squatted down in front of the sculpture and took the picture.

This possibility is even more convincing when one considers that the Yoga-Narasimha sculpture was on “tour” with the Master Bronzes of India exhibition. It thus appeared at The Art Institute of Chicago, September 3-October 10, 1965; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri, October 21-November 30, 1965; The Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio, January 18-February 27, 1966; and the Asia House Gallery, New York, October 12-December 11, 1966. It is possible that Kelley, or an acquaintance of Kelley, visited one of these museums, took a low-angle photo of it, and that it somehow made it to him. Remember, the Grateful Dead began recording their first album in January 1967 and it was released by Warner Brother’s Records on March 17. Kelley either had the image with him or obtained it within that three-month period, after the Grateful Dead asked Kelley and Mouse to do the cover.

Although there is no definitive proof (and there may never be), it is likely that a museum patron took the low-angle shot of the Yoga-Narasimha and that image made it to Alton Kelley in time to make the collage for the Grateful Dead’s first album cover.

But the question remains, why did Kelley choose this wonderful and dramatic image? Did he know the wonderful story of Narasimha, The Man-Lion form of Vishnu? Though Mouse is not Kelley, his insight into Kelley’s mind and mindset is probably the closest that we will ever come to concerning these pressing and intriguing questions. In an email correspondence Mouse writes:

It is odd that after looking at that cover a zillion time, I never noticed that Man Lion. It really makes the cover make sense to me.[14]

And then in a clarifying and perhaps conclusive message immediately following…

Maybe because Garcia was a Leo.[15]

Wow!

Fans, scholars, and scholarly fans may never know for sure why but Mouse’s intuition is about as close as we will ever get. In another email correspondence a few days later, Mouse writes:

The Garcia was a Leo is just a whimsical thought. I doubt if Kelley knew or even cared. But, Kelley had a seventh sense. He picked that image because of what he though it meant visually…Fun Stuff, Stanley.[16]

Fun stuff indeed! In any event, one thing that we can be sure of, the Grateful Dead, Stanley Mouse, and Alton Kelley were definitely playing, like waves upon the sand…[17]

Deepak Sarma, professor of Indian religions and philosophy at Case Western Reserve University, is the author of Classical Indian Philosophy: A Reader (2011), Hinduism: A Reader (2008), Epistemologies and the Limitations of Philosophical Inquiry: Doctrine in Madhva Vedanta (2005) and An Introduction to Madhva Vedanta(2003).

Notes:

[1] Jerry Garcia and Robert Hunter, Scarlet Begonias. (NY: Universal Music Publishing Group, Warner/Chappell Music, Inc., 1974.

[2] I am grateful to Sonya Mace, George P. Bickford Curator of Indian and Southeast Asian Art, Cleveland Museum of Art, for this connection.

[3] For more see Meister M. W. “Man and man-lion: The Philadelphia Narasimha.” Artibus Asiae 56(3–4):291–301, 1996.

[4] His story is related in a number of Puranas, including the Visnu Purana, (1.16-20) and the Bhagavata Purana (Canto 7), among others.

[5] Interview with Ralph Gleason, KSAN-FM, San Francisco, June, 1969. http://www.vidkid.com/GDdochome.html

http://deadsources.blogspot.com/2012/02/june-1969-radio-documentary.html

[6]https://www.reddit.com/r/gratefuldead/comments/6026yi/what_is_the_creature_on_the_album_cover_of_the/

[7] Email and phone conversation with Julie Mattsson, Registrar, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, March 2, 2018.

[8] Phone conversation with Mike Wilson April 4, 2018. I am grateful to everyone who helped me to connect with Mike Wilson, especially Anjali Belmann.

[9] Email conversation with Mike Wilson. April 5, 2018.

[10] Email conversation with Herb Greene, March 2, 2018.

[11] For more, see S. Mouse, A. Kelley, Mouse and Kelley, New York: Dell Pub. Co,, 1979.

[12] Master Bronzes of India. the Art Institute of Chicago and William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, exh. cat. (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1965), unpaginated, (repro.). #31.

[13] The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, “Checklist of Acquisitions 1962-1966,” The Nelson Gallery & Atkins Bulletin, 4, no. 8 (1967): 47.

[14] Email correspondence with Stanley Mouse, March 9, 2018.

[15] Email correspondence with Stanley Mouse, March 9, 2018.

[16] Email correspondence with Stanley Mouse, March 12, 2018.

[17] Robert Hunter and Bob Weir, Playing in the Band. (NY: Universal Music Publishing Group, Warner/Chappell Music, Inc., 1971.