Morgan Shipley

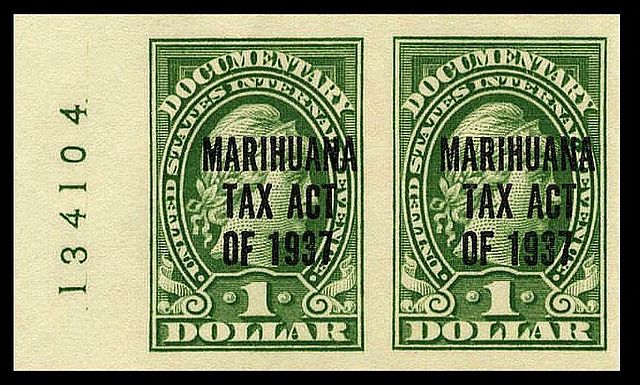

In 1937, the United States federal government enacted the Marihuana Tax Act, prohibiting the use of cannabis at a federal level while allowing for highly-regulated medical use. What was once both a popular recreational and therapeutic device had become, by the 1930s, a public nuisance connected primarily to communities of color viewed by white America as a threat to traditional American values. More stringent oversight came in 1970 when the federal government passed the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), adding cannabis to the list of Schedule I controlled substances, associating it with “drugs” (addictive substances without medical usage) that range from psychedelics like LSD or DMT to opioids, such as heroin. Although reflecting similar cultural, racial, xenophobic, and economic concerns, this move carried an additional consequence—the outlawing of what, for many, represented a historical and contemporary religious sacrament. Complicated further by the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) and the 2000 Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA), federal laws designed ostensibly to shield religious groups from governmental overreach, the function of cannabis in religious settings remains contested. In addition to legal restrictions that ban the use of cannabis in any environment, advocates and believers find themselves maligned within public discourse, relegating (even in light of the above laws) ritual use to the fringes of underground communities or religious subcultures who claim a form of autochthonous or historical use that predates—and thus overrides—the imposition of federal mandates. This outsider status only further compounds the proper space of the ritual use of cannabis on a spiritual level, while advancing the racist tropes (which continue to manifest today) directing both the original Tax Act and the CSA.

Even the spelling found in the tax act, “marihuana,” speaks to this reality, illustrating how fear of the other, in this case, an influx of Mexican immigration following the Mexican Revolution, directed early 20th century responses to cannabis use. Exemplified by the creation of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) in 1930, cannabis, as FBN head Harry J. Anslinger made clear, was a dire threat, a substance that led inevitably to bouts of madness defined by an insatiable appetite for (often sexualized) violence—a narrative furthered by relying on xenophobia and racist tropes of black men as sexual predators. Relying on the mass media, and often ignoring the counsel of medical experts, Anslinger constructed an anti-marijuana agenda into a national movement for prohibition, often drawing from his “Gore Files,” a collection of over two hundred unproven and mostly fabricated stories, quotes, and anecdotes about cannabis use, to illustrate the destructive capacity of cannabis. Exacerbated by propaganda films such as Reefer Madness (1936), which connects marijuana usage to a descent into psychosis defined by hallucinations, manslaughter, suicide, and attempted rape, initial fears regarding cannabis expressed illusory fantasies that pitted the perceived exceptionalism of American culture against a constructed, externalized threat. Once imposed upon oppressed and racialized groups, cannabis became a material outlier, an example of the taboo that not only debased the communal, economic, and citizenship arrangements of the United States but intervened spiritually by offering an avenue of religious growth and ritual practice untethered from the conventional Christian narrative directing America’s claim to exceptionalism and corresponding moral expressions.

In other words, the outlawing of cannabis speaks to the entwining of economics, culture, and religion in American history, exemplifying how constructed racialized fears of the other, and theological concerns regarding the proper (and exclusive) path to salvation, function contingently and reflexively to reify traditional power structures. In this way, the place and prohibition of cannabis in the United States help unpack cultural mechanisms of racialized difference (that we see, for instance, in American drug policy) while also demonstrating how projects of religious exclusion prevent the full flowering of religious diversity and pluralism. By wedding discourses of proper cultural attitudes to sanctified expressions of correct religious values, American exceptionalism necessitates viewing America as God’s nation of chosen people, as a “City upon a Hill.” Never intended by its author, founder of the Massachusetts Bay Colony John Winthrop, to be an inclusive call, the mythos of America exists tenuously against this backdrop, promising, as a nation, to be a safe haven for those seeking freedom and equality, yet often functioning, specifically when it comes to religious heresy, as a place of exclusion and intolerance. In this unique and often contradictory way, American religious history unveils a celebration of openness, of following Emerson’s call to “Obey thyself” when it comes to our spiritual authority, while simultaneously functioning through bounded narratives that limit the full realization of religious pluralism promised in the American Constitution. The contemporary rise of cannabis churches, both in their syncretic religious tendencies and often explicit efforts toward full legalization, capture this dynamic.

This is not to suggest that American religious culture is homogenous; far from it. However, the prohibition of cannabis and the contemporary rise of cannabis churches (as this article primarily engages) demonstrates the divide between cultural-religious exclusivity and legal-political guarantees, between America as a Christian nation and America as a nation of inclusive religious diversity. It exposes how the promise of pluralism remains obscured when theological concerns become functions of and for social control, economic privilege, and political authority. To see America as doomed to fail if it exists “without God,” as Ronald Reagan proposed, or as every president suggests when they declare “God Bless America,” is to construct a bounded identity, a specific type of national character capable of fulfilling, maintaining, and protecting this plan. The inclusive empowerment promised by the Constitution thus becomes secondary to the constant threat posed by non-traditional expressions of religiosity that, by their very existence, expose the costs of the “chosen” narrative: to be chosen means others are not. Throughout American history, this reality resulted in particular conditions that advance and empower the select at the direct expense of the disenfranchised. Any religion that challenges this exclusivity, offers space for pluralism to flourish, or provides access to the sacred realm outside the institutional frames of conventional Christianity, becomes a dire threat. And, while America demonstrates a profound ability to assimilate such groups over time, the place of substances within religious settings remains unceasingly contested, offering a site upon which normative religions stake claim to authenticity by denying foundational rights to who they identify and delimit as the operative other.

Yet as more states pave the way for the medicalization of cannabis use (currently 33 states allow for medical use), and with Michigan joining nine other states in the full legal, adult use of recreational cannabis, the demonization of cannabis as a substance of madness or a tool of and for intoxication, is beginning to crumble. Although efforts to reschedule cannabis have failed to realize concrete change through court challenges (see, for example, the United States v. Oakland Cannabis Buyers’ Cooperative [2001] or Gonzalez v. Raich [2005]), to see cannabis through the lens of the taboo or in relation to legal status fails to account for the entheogenic. Entheogens represent sacramental devices and are used to describe natural and chemical substances capable of generating a religious encounter (e.g., ayahuasca, peyote, soma, mescaline, psilocybin). These encounters are what Abraham Maslow calls the peak experience and what sages throughout human history identify as the noetic, esoteric, or mystical component of spiritual insight. For members of the International Church of Cannabis in Colorado (often called Elevationists), the Arizona-based Church of Cognizance, the First Church of Cannabis in Indiana, the First Cannabis Church of Florida Worldwide, the Healing Church of Rhode Island, THC Ministry: The Hawai’i Cannabis Ministry, the Lansing-based First Church of Logic and Reason, and the Coachella Valley Church of California, cannabis holds this very function.

While not unified across orthodoxy or theology, cannabis churches in the United States share a common belief that cannabis provides foundational access to the sacred, allowing for experiences of the numinous that historically manifest in world religions and, today, in more inclusive and less hierarchical expressions of spiritual exploration. Cannabis churches, then, do not seek to reify traditional religious structures, but rather create space out of which practitioners can return to the root experience of sacred wisdom (gnosis). Such an approach is not unique to cannabis churches alone, also manifesting in the ritual use of individuals and through “stoner bible studies,” the belief that using cannabis in conjunction with Christianity in a group setting enhances understanding and makes more immanent the encounter with God. For some churches, as with stoner bible studies, this manifests through frames of conventional religiosity, but with a shift in focus that highlights the sacramental potential of cannabis as a means to spiritually revitalize and communally re-connect, to return religion to its etymological root (religio-), which means to bind together. For many, the reliance on frames of conventional religiosity are enhanced not only by the sacramental use of cannabis but by the syncretic blending of multiple traditions to bypass the tendency toward religious exclusion to find the shared space of perennial spirituality.

The Healing Church of Rhode Island, for example, is unabashed in its connection of cannabis to traditional Judeo-Christian belief, seeing it not only as a historical sacrament but as a contemporary access point for the truths unveiled in Torah and the Christian Bible. More than a means for realizing religious conviction, the group ultimately connects the spiritual promise of Judaism and Christianity to the real capacity to heal at all levels of our being (physical, emotional, psychological, and spiritual). They cite Exodus 30:23 and Ezekiel 34:29 to support both their belief in cannabis as a holy herb and their mission to share “prayers, fellowship, and the healing medicine…[for] those in need of physical and/or spiritual healing.” The Church of Cognizance emphasizes this similar capacity of and for healing, positioning cannabis as haoma, a divine plant found in Zoroastrianism that the Church understands as being “the ancient teacher of wisdom, compassion, and the way to the kingdom of glory in heaven on earth.” While the group follows a Neo-Zoroastrian perspective, their real aim is to unite the oppressed and downtrodden through the consumption of a sacred plant (cannabis) capable of improving the mind and body through cannabis’s specific capacity to open people to living a life based on the core Zoroastrian morality of “Good Thoughts, Good Words, Good Deeds.” The First Cannabis Church of Florida Worldwide follows a similar dictum, simplified even further, however, to simply reflect a belief in the “Good” and the capacity, through the sacramental quality of cannabis, to awaken this intrinsic human value, thereafter creating the conditions, as the Church declares, to take active responsibility for “Vets, older people, [the] homeless.” The church, then, is not space to partake in cannabis use, but to gain a different visage, one that makes it incumbent upon each member to live with “Peace, Love, Happiness.” This manifests through real-world efforts (e.g., establishing small villages based around churches that would include greenhouses, gardens, learning centers, and refuge) to “make changes for the better and for a better world.”

For Elevationists (members of the International Church of Cannabis in Denver, Colorado), cannabis, when used ritually, offers a means for self-realization for those discontent with both conventional forms of religion and sacramental expressions limited by religious setting that deny the place of divine revelation. Adorned with psychedelically-inspired murals by artist Okuda San Miguel, the main chapel of the International Church of Cannabis reflects this purpose, signaling in its symbolic beauty the aim of Elevationists, who turn to “the sacred flower to reveal the best version of self, discover a creative voice and enrich our community with the fruits of that creativity.” Similarly, for the Lansing-based First Church of Logic and Reason, cannabis signifies a sacrament capable of breaking down the barrier between the sacred and the profane, between the rational and the ineffable, between the material and the spiritual. In this setting, cannabis deconstructs the enculturated mechanisms that assume a divide between the human and the divine. As with Elevationists and most cannabis churches, the First Church of Logic and Reason is strictly nondenominational. The unifying element is not belief in God, Jesus, Buddha, Shiva, or any other deity or leader, but rather the shared reality that humans turn to cannabis for spiritual and therapeutic purposes, to heal and find a sense of belonging, as Jeremy Hall of the First Church of Logic and Reason describes it.

Such an approach to experience a religion of no religion manifests maybe most directly in THC Ministry, who not only view cannabis as the original sacrament of most religions, but turns to evidence such as the anointing oils in the Bible—in a similar way as the Church of Cognizance turns to haoma—to support their theological and sacramental claims. However, at the heart of THC Ministry is not a commitment to Christ, but to a foundational and sacred right to use cannabis as a means to raise consciousness, to commune with nature, and, maybe most significantly, “live with modesty, good manners, and humbleness.” The ministry sees itself as a “universal religious organization that uses Cannabis to exalt consciousness, facilitate harmony, and become closer to God [however individual members define this] and Nature.” This approach of connecting cannabis to healing, both at the individual level and at the collective/global level, often dictates the orientation of cannabis churches; their ends are not to confirm denominational or orthodox certitude but to aid others. Greenfaith Ministry in Colorado, for example, states that it is a nondenominational church and charity, with emphasis placed on the fruits of their conduct, rather than on the roots of their awakening (e.g., the use of cannabis). Echoing William James’s assertion that we can assess the religious life, not in its rhetorical flair or faith-based proclamation, but in its expressions, in how a sense of spiritual truth or religious understanding manifests into action, cannabis churches demonstrate how cannabis does not lead away from religious insight but demands a response. This is what THC Ministry declares unambiguously as “foster[ing] a spirit of harmony and compassion among people.”

What these cannabis churches share, then, is not a commitment to religion as traditionally understood, as either an expression of institutional vitality or salvific security, but rather to a ritualized process to bypass the ego and authoritarian structures in order to access a space of communion, both with the broader natural world and with one another. Elevationists take their name from this dynamic, celebrating cannabis sacramentally as the means to transcend the self, resulting in a general outlook defined, as with many expressions of traditional religion, by the “Golden Rule.” As defined by Elevationists, “our life stance is that an individual’s spiritual journey, and search for meaning, is one of self-discovery that can be accelerated and deepened with ritual cannabis use. We use the sacred flower to reveal the best version of self, discover a creative voice and enrich our community with the fruits of that creativity.” Syncretic and perennial at its core, the message is not one of religious orthodoxy, but rather the potential to overcome the common bifurcation that defines religion by insiders and outsiders, thereby creating the conditions to actualize religious modes of being dedicated to the fruits of ethical conduct and not adherence to proper belief. The Church of Jesus Christ, located in Kaawaloa, Hawaii, exemplifies this syncretic perennialism, understanding cannabis as the sacramental means to access a collective space that finds expression through traditional understandings of a Christian God (“God is Our Father”). The group fully embraces the Urantia Book, which they understand as “a unifier of the world’s religions” that “allows” the group “to draw upon the broad scope of human religious experience in the determination of the form our religious practices take.” For members, cannabis works to dispel the myth of separation, pulling back the veil to reveal how “we are all, the entire human race, one spiritual family.”

This does not mean, however, that efforts toward medicalization or legalization have opened without controversy the ritualized use of cannabis. Still illegal at a federal level, cannabis churches find themselves straddling legal structures while at the same time often being denied foundational rights promised by U.S. regulations. For many, cannabis remains a drug and is not only unviable as a sacrament but debases the very meanings and expressions of American religiosity. Beyond claims of heresy and blasphemy, others challenge the very notion that these groups represent anything more than political attempts at full legalization. We see this, for example, in a judge granting Jurupa Valley legal authority in August 2018 to shut down the Vault Church of Open Faith, arguing that the church’s distribution of cannabis as a religious sacrament is a con, a way to manipulate bans on dispensaries. Because many groups deny any allegiance to conventional religious traditions while also pursuing socio-cultural and political change as it relates to the legal status of cannabis, some view these churches as political trolling devices, groups who turn to religious freedom to challenge political laws that impose restrictions on individual sovereignty.

The First Church of Cannabis, for instance, was founded in March 2015 by Bill Levin as an act of religious expression in direct response to Indiana’s controversial Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA). This should not suggest that the group does not see itself as an intentional gathering of like-minded individuals who desire to create a church of collective believers, holding broadly to universal precepts of love, compassionate acceptance, and living a good life. Yet Levin’s entirely constructed foundational tenets, known as the “New Deity Dozen,” and his reliance on Jack Herer’s 1985 The Emperor Wears No Clothes: Hemp and the Marijuana Conspiracy as the Church’s first foundational sacred text, demonstrates how much of the First Church of Cannabis pushes the boundaries of the RFRA. Its fight to use cannabis in religious settings and advocating for its legalization often results in disparaging responses or questions about the Church’s sincerity (a common reaction as it relates to contemporary cannabis churches). Offering a safe haven and communal space, Ed “NJ Weedman” Forchion’s Liberty Bell Temple in New Jersey exists similarly, turning to religious freedom as a means to push for broader legalization as a reflection of individual right. None of this should suggest that Levin and Forchion do not fully understand their groups as religions and their churches as religious; instead, their willingness to push back against government infringement demonstrates how religious freedom echoes the demands of individual freedom, both expressions of America’s (ideal) historic effort to create space for all people amidst a real history fraught with exclusion. In this way, some cannabis churches may be more in line with the Satanic Temple, a contemporary new religious movement that draws from the expectations of religious freedom to challenge the imposition of exclusive religious and ideological beliefs within American politics. Using Satan as a symbol of individual will, the Satanic Temple see themselves as classically American in pushing for a political world that allows for the equal rights and freedoms of all believers and expressions of belief; limits should only exist when one religion or group claims rights over another.

Maybe most distinctly, then, the rise of cannabis churches signals a common, though contradictory, reality when it comes to American religion. Though mired in discourses of religious freedom, the history of religion and religious movements in America demonstrate an ongoing negotiation between the sanctity of individual spirituality and the viability of institutional religions often positioned as omens of political might. Against the backdrop of American currency validating God’s place, or the condition that seemingly requires all presidents to be dedicated and clearly delineated Christians (the Birther Movement alone helps reify this standard), cannabis churches intervene on the coherency of the America-as-Christian nation narrative while simultaneously exemplifying a cultural openness to explore alternative traditions that speak to the individual, communal, and sacramental needs of believers. In this way, cannabis churches become idyllically “American,” capturing the promise of the exceptionalist narrative of individual will and sovereignty without the baggage of exclusion and othering. Within the diverse and syncretic expressions of cannabis churches, we witness a melding together of spiritual people who seek an expression of religious practice and truth that accounts for collective needs by advancing their rights. Because the religiosity ranges so profoundly within these settings, cannabis churches capture the promise of contemporary pluralism while returning religious experience to embodied encounters. Once untethered from traditional settings and orthodox conditions, these churches and practices advance not only the growing tendency among Americans to identify as spiritual but not religious (see Bill Parson’s “On Being Spiritual But Not Religious: Past, Present, Future[s]”), but also demands that all of us reconsider what is meant by the invoking of the religious.

Morgan Shipley is a Continuing Academic Specialist and the Academic Advisor in the Department of Religious Studies at Michigan State University. His research focuses on new religious movements, mysticism, western esotericism, and alternative spirituality in America, specifically through analyses of popular culture representations, social movements, socio-political exclusion, and identity structures.