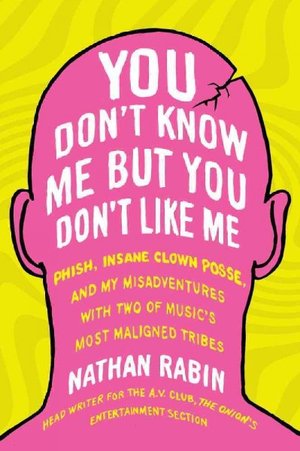

In our new interview series, we ask cultural theorists about what inspires them and how their latest work challenges our understanding of the sacred in American cultural life. For our inaugural segment, we chatted with The Dissolve’s Nathan Rabin about his latest book, You Don’t Know Me but You Don’t Like Me: Phish, Insane Clown Posse, and My Misadventures With Two of Music’s Most Maligned Tribes.

1. What sparked the idea for writing this book?

It was inspired by my now wife’s teenage and college years following Phish and other jam bands across the country. It was a side of pop culture that was utterly foreign to me but also incredibly seductive. I initially saw the book as the ultimate working vacation: here, I could take drugs and travel the country with my girlfriend seeing music every night. What could be better? It ended up being a far more complicated and difficult endeavor. By the end, I felt like it was something I survived as much as experienced.

2. Is there something sacred about or within the Phish and Insane Clown Posse (ICP) subcultures? How does it function for the fans?

I would definitely say that there is something sacred about the Phish and ICP subcultures, something that transcends the mundane and everyday and connects fans with forces that are larger than themselves, whether that is history or the mythologies of the groups, or in the case of ICP, a genuine alternative spiritual belief system in the form of the iconography and rituals surrounding the Dark Carnival. At its peak, a great Phish show or a Gathering of the Juggalos offers an experience beyond words, beyond reason, and beyond explanation. Drugs have something to do with it, but that feeling is reachable through sobriety as well and some of the most passionate and devoted Phish fans are also the most sober; for them, the experience of becoming one with the crowd, and the band, and the music, and their own histories (as well as the band’s) is its own kind of high, its own altered state, and one without the myriad drawbacks that come with drugs.

3. Can you summarize the three key points you’d like the reader to walk away with when finished?

I think first and foremost, I would like for readers of You Don’t Know Me to not judge things harshly without knowing anything about them. I think there’s a knee-jerk negativity in our culture I find really depressing, particularly on the Internet, and this book is a manifesto against the lazy, everything-sucks mentality pervasive in our culture. I think the book also highlights the sometimes life-affirming sense of community among Phish fans and Juggalos, and how it transcends music and become a positive spiritual force in their lives, and connects them to other people. Lastly, I suppose the book is an inducement to actually listen to Phish or ICP or go to their shows, although that is a step I suspect many readers will not take.

4. Who are your inspirations or intellectual models for you as you wrote this book?

I suppose my two greatest inspirations were Hunter S. Thompson and George Plimpton, two journalists and writers who threw themselves into their stories with wild abandon (in Thompson’s case) or genteel curiosity (in Plimpton’s). I set out to be Plimpton, but as I got crazier and crazier and skinnier and skinnier and the hair on the sides of my head began to grow out, I even began to look Hunter S. Thompson, so it was enormously flattering to get Thompson comparisons in places like Rolling Stone.

5. What was the most difficult thing about writing the book? Did you encounter any unexpected problems or challenges?

Everything was the most difficult thing about writing the book and I encountered nothing but problems and challenges. Surmounting those challenges and problems accidentally but inevitably became the overarching theme of the book. Let’s see: I ran out of money, I ran out of time. I jeopardized my career at The A. V. Club by needing to take so much time off and spent an entire year working on the book and being crippled with writer’s block as I tried to figure out how on earth I was going to finish a book I didn’t have the time, money, or direction to do justice to while simultaneously working on a second, vastly different book (Weird Al: The Book), and hold down an incredibly stressful and demanding full-time job. All this stress and pressure forced me to a dark and brutal place psychologically, and that ended up being the starting place where I begin what is the core of the book: my travels following Phish in the summer of 2011.

6. What’s the most unexpected response, critical or positive, that you’ve gotten about the book?

When I wrote this book, I thought the subject matter and point of view was so fucking strange (a dude having a nervous breakdown while becoming a big fan of two wildly dissimilar, wildly reviled groups with no overlap whatsoever in terms of their fan base) that it would have no audience, so it’s been a huge relief to have people connect to it so emotionally. I like to think [people are connecting] because fundamentally it’s about a whole lot more than these two weird bands in their fans—it’s about the search for meaning, and community, and a sense of belonging in a world that can often seem insane and cruel.

7. With this book done, what’s up next for you?

We just started The Dissolve last year so I am focused intensely on that, and then my wife is expecting our first child in November, a boy. So I am very much focused on my job and my family, although heaven knows I would love to write more books and this brain of mine is forever swimming with ideas. I also think I might be in a better place to work on the next book because I am no longer out of my mind and filled with dread about anything and everything.

Nathan Rabin is a staff writer at The Dissolve. Previously he was the original head writer for The A. V. Club for most of his sixteen years there and the author of four books, including The Big Rewind:A Memoir Brought to You by Pop Culture (Simon & Schuster, 2010) and You Don’t Know Me but You Don’t Like Me. He can be followed @nathanrabin.