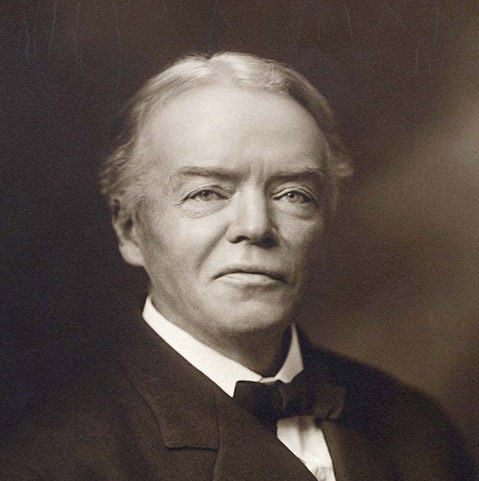

Jonathan Orbell

When my wife suggested we go out and see Pixar’s newly released Inside Out, I agreed, albeit reluctantly. “I’ll be asleep within 20 minutes,” I thought. Suffice it to say, I’m not really a “kids movie” kind of guy; more of an “old soul.” I was in for one hell of a surprise.

Inside Out consists of two parallel storylines. The first, occurring in the “real” world, tells the story of Riley (Kaitlyn Dias), an 11-year-old Minnesotan girl whose family moves out to San Francisco. The second, taking place inside Riley’s mind, follows her five emotions – Joy (Amy Poehler), Sadness (Phyllis Smith), Fear (Bill Hader), Anger (Lewis Black), and Disgust (Mindy Kaling) – as they guide Riley through this turbulent season.

For the first 11 years of Riley’s life, Poehler’s Joy carefully manages the other, negative emotions in a manner strikingly similar to that of Leslie Knope. She never gives them too much authority over the control panel responsible for producing Riley’s external responses. While Joy reluctantly recognizes the use of emotions like Fear and Disgust, extraordinary effort is directed at constraining Sadness. Riley should never have to be sad, right? As a result of Joy’s micromanagement, Riley grows up a kind, lovable goofball; a little “bundle of joy.”

After relocating to San Francisco, though, things change. Despite Joy’s mildly tyrannical policy of containment, Sadness has this annoying habit of touching Riley’s happy memories, thereby transforming them into gloomy ones.

In a poignant moment near the end of the film, Joy finds herself trapped in Riley’s memory dump, a dark abyss where long-term memories go to be forgotten. While there, Joy goes through some of Riley’s core memories — recollections of particularly formative moments in the child’s life. One of these memories portrays a young Riley after missing the potentially game-winning shot in one of her hockey games back in Minnesota. At first glance, this memory appears wholly sad.

As she continues watching, however, Joy realizes that Riley’s sorrow brought her family closer together. As Riley’s mother and father try to console her, the memory adopts a distinct element of happiness. Indeed, the two components – joy and sadness – were entwined. As much as the film is about Riley’s transition into a new phase of life, it is also about Joy’s confrontation with the reality and the necessity of Sadness.

Inside Out reminds viewers that, despite our attempts to insulate ourselves (and our children) from difficulty, there is something meaningful about walking through the struggles imposed by our imperfect human existence. A “good life” is not defined by the absence of suffering. In a sense, life would be incomplete without trial, tribulation, or adversity.

One of the film’s major achievements, then, is that it presents viewers with a particular notion of “theodicy.” It inadvertently answers one of theology’s perennial questions: How do we explain the existence of suffering and evil in a world supposedly ruled by a benevolent, omnipotent deity?

A number of the Christian tradition’s theological heavyweights have addressed this issue. Augustine’s understanding of theodicy remains the most well-known. Suffering, for Augustine, emerges as a result of Adam’s original sin. It is an unnecessary perversion of God’s perfect creation, lending credence to the notion that suffering is to be avoided. If God originally intended our lives to be free of suffering, what use could there be in enduring it?

If forced to articulate a position on theodicy, I think Joy would have placed herself firmly in the Augustinian camp, at least at the beginning of the film. I leaned over to the five year old on my right and tried to explain this. All I got in response was a blank stare. Have I mentioned that I’m kind of an old soul?

While the Augustinian notion of theodicy has enjoyed broad acceptance among Christians, it differs sharply from the vision offered by Inside Out’s creators. Pixar’s explanation for suffering aligns most closely with another, less well-known, philosopher: Josiah Royce. One of America’s leading idealist philosophers during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Royce wrestles with precisely this question in “The Problem of Job.”

How could a supposedly good, all-powerful God allow the existence of evil and/or suffering? Does suffering have a functional role to play in human life? Can we take solace in the fact that our suffering has meaning? Royce clearly thinks we can.

For him, God is so thoroughly immanent, so deeply with us, that it is possible to speak of an “absolute oneness” of God with the sufferer. When we suffer, claims Royce, God suffers with us in precisely the same way.

This seems strange to some readers, particularly Christians. Is he really saying that God, the creator and sustainer of the universe, suffers?

In a sense, yes. God chooses suffering as part of His own “perfect selfhood.” If our goal is to become ever more like this perfect God, we should not insulate ourselves from suffering, as Joy would have us do, but calmly accept it as “a logically necessary and eternal constituent of the divine life.”

Part of modern readers’ difficulty with Royce comes in the particular way he defines God’s “perfection.” We tend to conceive of perfection as “without flaw or blemish,” while Royce thinks about it as a sense of completeness or wholeness. Understood in this light, suffering “completes” God. So too for humanity, our lives or made more perfect (read: complete) when we are confronted with the painful reality of suffering and evil.

Admittedly, Inside Out’s 11-year-old protagonist is not seeking a “divine life.” The film’s story is a humbler, although no less miraculous, one about the transition to young adulthood. However, the film’s writers surely agree with Royce on this: suffering is necessary, and it does something to those who endure it. Without suffering, one has not experienced the perfection (read: wholeness) of human life.

Inside Out betrays its Roycean nature most clearly in the evolution of Riley’s memories over the course of the film. As Joy, Sadness, Anger, Disgust, and Fear twist the knobs on Riley’s emotional control panel, memories are produced in the form of colored, glowing orbs. Each orb’s color corresponds to the particular emotion characterizing that memory (i.e. yellow indicates a happy memory, blue a sad one, etc).

At the start of the film, Riley’s memories are one color or the other. There are happy memories, sad memories, fearful memories, and so on. However, after Joy is confronted with Riley’s need for Sadness, Riley’s memories take on unique mixtures of emotions. Joy and sadness can now coexist in a single memory. It’s not that Riley’s life is now “less happy.” Sadness is not simply infecting what were once happy memories, as she did in the beginning of the film. The narrative clearly depicts this change as a positive one, and that Riley is now a better, more well-rounded, individual.

What’s more, this development likely would not have happened if Riley’s life had been, as Joy originally intended, devoid of pain and struggle. In a Roycean sense, her story would be incomplete.

I must say, it’s easy to wax philosophic about suffering when you have a roof over your head, food in the fridge, and a savings account. Because of this, I find myself ambivalent about Royce’s notion of theodicy. Any explanation for suffering’s existence, even those that appear convincing at first, seems to crumble under the weight of lived human experience.

If a friend came to me in a moment pain or anguish, I wouldn’t attempt to persuade them that their suffering “is a logically necessary and eternal constituent of the divine life.” I would, instead, take a note out of Sadness’ book.

When Bing Bong (Richard King), Riley’s imaginary friend, is confronted with his impending disappearance — Riley’s imagination now fantasizes about more grown up things, like boyfriends — Joy tries unsuccessfully to comfort him.

“Hey, it’s gonna be OK,” she encourages Bing Bong. No response.

“Here comes the tickle monster!” she exclaims. Still, nothing.

Dan Kois describes the next moment, and what I felt was the film’s overarching take-away, well: It’s Sadness who knows, instinctively, how to treat Bing Bong. “I understand,” she says quietly, sitting next to him. “They took something that you loved. That’s sad.” Joy looks on, irritated, as Bing Bong sobs on Sadness’ shoulder — but then Bing Bong sniffs, wipes his eyes, and feels a bit better. “How did do you do that?” Joy asks Sadness, bewildered. Her entire existence, up until now, has been focused on eliminating, or at least minimizing, negative emotions; it’s never dawned on her that Sadness has a role to play too.

Sometimes, all we can do is be present with another person, resting in the assurance that, while we may be unable to rationalize their suffering, our faithful presence in its midst is all we can offer.

Jonathan Orbell is a writer living in the San Francisco Bay Area. He is currently a graduate student pursuing a Masters of Theology at Fuller Theological Seminary. He can be followed @JonOrbell.