Ludwig Wittgenstein responded to the outbreak of World War I by joining the Austrian Army as an artillery corpsman. Twenty years later, he abandoned teaching at Cambridge University to enlist as a hospital orderly, while his colleagues (some of them) toiled at desks in British Intelligence. In his twenties, he was true to his Austrian roots and later he was true to his recently grafted British roots. He had a primitive, non-intellectualized hold on some truth he should be true to, something that was real to which he should witness. He lacked any articulate basis for regarding that witness as a witness to truth rather than to illusion or falsehood. Yet his actions showed that in his fifties, he could be true to British soil without being false to Austrian terrain and he could be true to Austrian terrain (earlier) without desecrating British soil. His later British loyalties were not a self-betrayal.

Søren Kierkegaard (Wittgenstein knew him well) remained true to Christian roots even as he was true to his pagan, Socratic roots. He was an unrepentant pluralist, not because he looked out across a dizzying array of religious possibilities and realized that there must be a truth in each. An opinion about differences or similarities among world religions would tell him nothing about how he should live, where his loyalties lay. He knew he was fully Christian and fully Socratic,and that neither loyalty betrayed the other. Neither Christ nor Socrates, as Kierkegaard saw it, put much stock in winning anyone to a creed. That a Christian—in a Kierkegaardian way—can be unreservedly Pagan—in a Socratic way—is a thesis that I’ve defended. A young colleague wrote to me tentatively from Israel: “Does that mean that one can be fully Christian, fully Socratic, and fully Jewish?” Of course, she’s right: one can.[1]

On his deathbed, at the conclusion of what can only be called a tormented life, Wittgenstein asked his comforter, “Please tell them I’ve had a wonderful life.” He spoke truthfully, I’m sure, though that witness was nothing that he, or anyone else, could confirm as true. Wittgenstein was not uttering a proposition to be tried and found adequate to some state of affairs. He spoke truly, witnessed truly. I often imagine Kierkegaard witnessing from his deathbed, despite his Christian torments, “Tell them I’ve had a wonderful, a wonderfully Socratic life.” The moral here is that a plurality of truths is not evidence for the absence of truths—or truth. (This is an error Nietzsche and others can fall into. To say that truth is perspectival, always delivered from a perspective, does not entail that there is no truth. From the perspective of an ant, humans are very large—that’s a truth; from the perspective of a whale, humans are not that large at all—that’s a truth.)

Speaking at Syracuse a few months ago, Helene Cixoux confided to the sweet touch of shared words over her years with Jacques Derrida. She was a true friend to him as he lived and a true friend to bring him alive, as she did, far from Paris that day. She delivered truth to those with ears to hear: a resonant truth, a tactile truth, a truth that touched and blossomed from touch. Like Kierkegaard and Wittgenstein, she witnessed truly to a quality of life. Truth matters.

Speaking in a large public stadium in the wake of 9/11, a Lutheran pastor shared a space of prayer with imams and rabbis and priests, witnessing not to friendship but to true and truthful communion across sectarian lines. In distain for such truth, he was defrocked forthwith. Witness is not trouble free. Through his comportment, he embraced Islam and Judaism while wedded to Christianity. He might have whispered, “Tell them that there, for the moment, I was Muslim and Jew.” He was truly exemplary of solidarity in mourning and compassion across faiths and non-faiths.

Truth matters because we yearn for it and because we’re up to our necks in untruth. Disparaging Big Truth, Richard Rorty left a constraining Princeton for a looser Virginia and then moved on to hang-loose California. His replacement, as it were, Harry Frankfurt, speaks for tactile truths from Princeton in a little book called On Bullshit. If you want to expose BS, you’d better believe in truth. Truth is triumphant as BS gets outed. It glows also in true witness, true communion, true friendship, true service—in being true to oneself and others. My apprentice must “true up” the juncture of that beam and its support. Perhaps it’s asking too much to have politicians live truly, but we want John Wayne to have true grit. To dump truth is to dump the goodness of Wittgenstein’s service, the beauty of Cixoux’s friendship, the witness of a Lutheran pastor, the incisiveness of Frankfurt’s polemic against BS. To scorn truth is to leave untruth standing. If a madman cries out that truth is dead, you can block your ears or send him away.

II.

We don’t need a theory of truth to grasp truths of witness, communion, or friendship any more than we need a theory of music to grasp Beethoven’s invincibility, his immortality. We don’t need a theory to grasp Thoreau’s witness to the Concord and Merrimack as revelatory sites, sites of truths. Knowing the landscape, we have an instinctive grasp of BS (Frankfurt helps us sharpen it). Knowing the field, we have a grasp of the quarterback’s true vision, true grace under fire. Doing considerable reading in Thoreau country, we can grasp the truths of his witness—in writing, walking, and civil resistance.

Getting to religion’s tactile truths is getting around in the landscapes of prayers, tears, and apocalypse; getting the feel of confession, pieties, and beloved mothers; of absent fathers, envies, loyalties, fear, and trembling. These terrains are enlivened as we trace how Buddha or Jesus or Gandhi cut through them, interrupting and disrupting and reassembling as they go. We get a knack for their witness to the lay of the land and to the things and practices it embraces. We move among tactile truths.

The thought of tactile truth is linked to Wallace Stevens’s invitation to let poetry give us “Not ideas about the thing, but the thing itself.” And to be given “the thing itself” is a gift to touch, not an idea about what touches us. For Thoreau, death appears on a Fire Island beach as the bones of his friend Margaret Fuller, close enough to touch. He works for a harmony of head and heart, ear and eye, nose—and hand.

A few years ago at a conference at Wheaton College, a speaker evoked El Capitan’s walls in Yosemite as a site where a climber could have tactile knowledge of an exhilarating, timeless moment, an Augenblick, or series of them, high above the valley floor. There was witness to tactile truths revealed to the living body, truths of the most extraordinary kind, available nowhere else and in no other way than by inching one’s way up the granite face until a thousand feet dropped off below, and thousands more beckoned above. Truth spoke from the rocks and the climber alike—from the skies—and to those viewing rooted in the meadows below. The moral is that tactile truths, and witness to them, get us through the night.

Pilate asks, “What is Truth?,” but his interlocutor ducks, as he should. The question is doubly mocking, of truths and of the exemplar before him. If my son gathers his equipment to attempt an ascent I think he’s ill-prepared for, I won’t halt him at the curb and ask “What is truth?” I’d ask, if he were young and ill-prepared, “What’s up with your foolhardy ways? Why shouldn’t I ground you?” Pilate is also asking, but of Jesus, “What’s up with your foolhardy ways? Why shouldn’t I ground you, or worse?” He needs a tactile sense, a grip on what’s up with an ill-dressed man who, it’s rumored, witnesses to being all that a true human being in fact is and should be, who comports himself as if he’s an exemplar for others. Perhaps his detractors fancy that he takes himself to be a true king relative to others. Pilate wants a story to tell, to himself and any who might question him later, about what’s up with this trouble-maker/ prophet/teller-of-parables/ harmless-miracle-worker/delusional-self-styled-king/insufficiently-humble-wanderer/disrupter-of-the-temple-stock-exchange—what’s up with this person who says he’s the way and the truth—what’s up with him, and what will he, Pilate, do about it.

In my view, Pilate couldn’t care less about the truth that good academics in theology and philosophy ask graduate students about in PhD qualifying exams. In their allotted hours, our good students run the gauntlet: “What is truth?” Well, let’s look at skeptics, conventionalists, pragmatists, deconstructionists, pre-postmodernists, semanticists, Platonists, nominalists, Aristotelians, etc. What’s wrong with this picture? Well, this is precisely not truth seeking—but why? Truth seeking culminates in a witness to truth or to its absence. It does not culminate in a theory about truth.

For a theory of truth, we assume that there’s a neutral “view from nowhere” from which we can announce “there is no truth” or “truth is what works” or “truth is the interest of the stronger” or “truth is a distillate of gender, history, and genes—not to mention a distillate of party affiliation, income, and having or not having resolved one’s Oedipal issues.” Or “truth is a distillate of anyone’s mood, his mood of the moment.” But I’ll get off this train, if you please; there’s something deeply untrue in the direction these tracks are going. I’m not skeptical about truth. I’m skeptical of proceeding at this non-living level of generality, at this great distance from the street.

“Is it true that Derrida had an aversion to binaries?”—I can handle that. I’ll consult texts and come up with something at least passable. “Is it true that binaries bully our perceptions and discourses?” I’m not clueless about how to argue, one way or the other. “Does Derrida smuggle in a false absolute, the ‘absolute truth’ that you can’t get deeper than binaries—or is his view here just an offhand remark that he’d retract in a moment?” I can handle all this. Truth has a grip, there’s a road and the rubber—and one hits the other.

However, if I hear yet again, “But come, just what is this . . . this ‘truth of the matter’ that you so confidently invoke?”—if I hear that, I shut down. I head for the door. Or get shrill or insistent. The question sounds deep but is in fact mere air.

Asking about truth is not asking about One Big Thing but asking about true witness, true friendship, true communion—no more, no less. It’s asking about true liars and true BSers, about true heroes and true villains; it’s asking whether binaries push us around or whether global warming is upon us—no more, no less. There is no Big Question about Truth left over, still to tackle, after thinking about these truths (or falsities) from the street. There is no Big Question about Truth—say how to define that Big Thing—we have to answer before we dig in to ponder true witness, true friendship, and so forth. If someone persists “But what is truth—in general, overall?” Then we should, like the good Socrates, artfully change the subject, or tactfully get off the train. Or offer very modest, push-cart versions: “a ‘true X is the best of its kind”—whether a true musician or true Christian, a true description or a true scholar. To give the idea a range of application, from low to high, I’d offer a parallel push-cart version: “a true X is a legitimate instance of its kind”—not a counterfeit or a forgery, but not necessarily the best of its kind.

I’d stick with push-cart versions, but not because Big Truth is a messy and difficult part of the city. I’d get off the train advertising Big Truth as destination because like Gertrude Stein would say of Oakland—“There’s no there there”—no there to go to. To knit one’s brow and worry the question “What is truth?” is to try to think from a supra-celestial nowhere, surveying all time and eternity. It’s to try to think oneself into divinity. More ornately, to ask The Big Question is to beg a release from Dasein, a release from Heidegger’s “there-ness.” It’s to presume exemption from the only field from which sensible questions about truth can be safely launched.

“What is truth?”—overall, in general—is a rootless, hopeless, slightly inane question. It flutters weightlessly in gossip and chatter. Emerson anticipates wonderfully. “We are place,” he announces.[2] That is, we are not gods, not disembodied consciousness, not exempt from placement, from the street or the village. Thoreau would agree—from a pond not far from the village of Concord.

If we are place, what is our place? Our place is the place that addresses us, and the place that addresses us (me) enjoins a regard for truth. It will have no truck with lies and falsehoods. The oak or the neighbor or the sunset have no use for dissimulation; they require my frank response. If I am the context, the place of my friend’s address, that friend can insist that I be true. We hope persons with religious sensibilities admire true human beings outside the circle of their practice, and if we are outsiders to each other, we might still ponder the true aims of argument, prayer, confession, or prophecy. It is our place to be moved by gestures of true friendship or true solidarity, to acknowledge the true magnificence of granite walls, or of a truly ripe Camembert. It’s truly our place to respect the quiet of another’s prayer and listen to chants in languages we don’t understand. The moral is that I know these truths of appreciation and comportment like the back of my hand. Might I be wrong? Of course. Might I be right? I’d better believe it.

III.

Getting truths from the trenches (or the streets) calls for a kind of tactile ability to sense what to trust and what to mistrust, what’s exemplary and what’s third-rate, what’s “true love,” “true friendship,” “true pitch,” “true aim”—and what’s a shoddy simulacra. Working toward the genuine, toward the shining exemplar, is a knack, something we pick up—or don’t. Some can’t miss a shill or a conman, others predictably do. Some light up at a true cabernet, others don’t. Some see Jesus as king, others won’t. Some will hear genius in Dickinson and others will miss it. There’s a knack for tactile truths, visceral truths. We get it from the streets or in classrooms or under temple roofs or Concord skies. We are the place where these truths get worked out and negotiated, where we absorb their touch and scent and ring. The truths we have a knack for detecting are not true propositions we can pocket and consult when we’re lost. Having a knack for the tactile ones allows us to hear the truth in Wittgenstein’s deathbed words, “Tell them I’ve had a wonderful life,” or to grasp the truth in his honoring newly grafted British roots, or to grasp the truth that he doesn’t thereby uproot his Austrian ones. With this knack, we hear Cixoux’s celebration of friendship and intimations of persecution.

Is truth objectivity? In science, in law courts, in serious journalism, we aim to attain it. We aim for objectivity, and when we achieve or approach it, we pride ourselves on realizing some passable degree of it. There, we seek truths-of-objectivity. In science, law courts, or serious journalism we aim for objectivity in reports and descriptions, because in those contexts objectivity is the genuine thing to pursue, the real thing, the best of its kind. If we miss objectivity, we feel shame.

Is truth subjectivity? It is when the domain of attention insists that I be true to what I am and must be as a human being, insists that I probe and weigh my passionate investments, and not refuse an awareness that I count for something and that the world can surprise. Subjectivity is, among other things, acknowledging responsibility, and that’s a good thing, something to be true to. To answer for oneself is an individual imperative that flows primitively from me, not from the “objective” spirit of culture or city or commonplace gestures and platitudes of the time.

Truth is objectivity; truth is subjectivity. A deep personal investment in honest scientific research weds subjective truth and objective truth. Einstein’s embrace of relativity coupled his embrace of objective truth with witness to subjective truth, so tightly was his identity coiled around it. And some truths are perhaps neither one nor the other. I have a true taste for Camembert and Richter has a true touch for Schubert, but these truths are neither the outcome of reliable, verifiable reporting nor a responsible witness to a personal investment. And there’s the subtle point that an ear for BS is something other than an ear for the absence of objective truth; it’s closer to having an ear for the betrayal of the subjective truth that truth matters to me. Across large reaches of our dealings with truth, we hardly know what to say about subjectivity and objectivity. We learn to sort the sham from the real, the true from the false, the deep from the shallow. We learn to sort the objective from the subjective and the instances of neither and both. To sort is to have a knack for attunement to the varied landscapes I pass through. Learning music is getting the gist of its spirit, the gist of true pitch, true expression, true regard for a composer and one’s fellow performers.

IV.

How about religious truth, or truths in religion?

It’s best to think of religions on the street rather than seek them and their truths sequestered in heavenly raptures. The rubber hits the road when we look for religious truths, sometimes with a deadly crash. In a violent emergency, it’s best to steer away from the hopeless question “Which religion is true?” away from the presumptions that Pilate’s question makes sense, and away from the illusion that if we only knew the answer we could adjudicate other people’s lives in light of that answer. There is no such light or answer. What we can do is to steer for an insider’s knack. We need a knack for the truth not of a bulk item, “religion,” but for the tactile truth of a singular lilt of a haiku, of the feel of a prayer shawl, of the taste of communion bread and wine, of the ornate patterns of tile-work in a cathedral in Byzantium.

Little is gained philosophically by a fixation on the spectacular clashes of one so-called religion with another. And to minimize the debilitating fallout from such clashes, we need to stay in the trenches, work harder for the tactile feel of ways of singing, praying, burying, wedding, blessing, forgiving, praising, meditating, walking, dressing, eating—and how these weave in and out of things holy and sacred, polluted and corrupt. Staying in trenches means learning aspects of Quaker quiet and of Orthodox iconography and of Staretz Silouan on Hell and Despair. It’s to have a feel for Buddha on the afflictions of age and wealth. It’s being able to smile with Eckhart as he confides, with a twinkle, “My Lord told me a joke. And seeing him laugh has done more for me than any scripture I will ever read.”[3]

If I’m worried about religious sensibilities or truths that seem strange or threatening to me, it wouldn’t help to ask “What is truth?” It wouldn’t help or head off on a NEH-funded research program. I’d ask, at street level, from the trenches, “May I listen in? May I sit with you?” That might lessen the chasms between my sensibilities and yours, letting me get some small knack of your sense of true friends, true prayer, true blessing, true dance. That will not close all the gaps between us; nothing can and probably nothing should.

At the level of institutional conflict, it’s doubtful that having a more intimate sense of another’s religious truths will eliminate violence, though it might bring the level down a notch, for a moment. But we should no more expect theories of truth or immersion in another’s ways of life to bring contesting religions together, than we should expect theories of truth or immersion in other’s ways to bring warfare or hatred or greed to a quick end.[4]

Let me close with two instances where I’ve had small but important glimmers of hope—places where rubber hits the road and one knows one has hit something significant.

A recent graduate of Duke, Peter Dula, now has a book on Cavell and theology.[5] A pacifist, he served a year in neighborhood shelters in Iraq with the war going full tilt. We’d learn more from his tactile sense of truths—truths of hope and faith under fire—than we would, I suspect, from reading a thousand essays on truth and pluralism. The truths he can witness to resonate with the cry of Starets Silouan, “Keep your mind in Hell, and Despair not!”[6] His witness is Gandhi’s or Simone Weil’s.

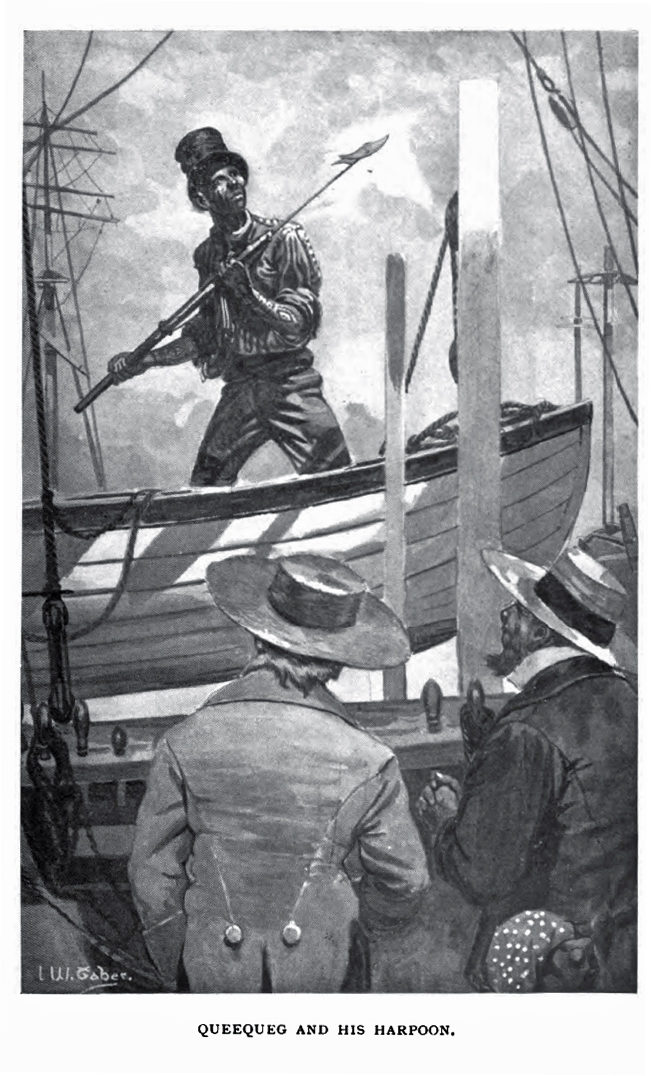

A woman wearing a Muslim scarf sits quietly in a summer class I lead at a local Catholic college. She’ll teach me something without uttering a word. I have no theory of truth or handbook for negotiating religious difference. I’ll be alert to Melville’s text in new ways. I linger with the delight Ishmael and Queequeg take in each other in their room at the Spouter-Inn. One celebrates Ramadan, the other Christmas; one shyly covers his feet, the other shyly covers up other parts. One sleeps with a knife, the other doesn’t. One drapes his arm comfortably over his bedmate, the other is terrified. They become best of friends.

Queequeg invites Ishmael to join in his pagan ritual. Without batting an eye, Ishmael thinks, “I would do as I would have done to me—I would have Queequeg join me in prayer; I will join him in prayer.” He arrives at a tactile truth, not unlike that of our good Lutheran pastor and all for the good. My scarfed student listens.

No doubt I’d have a sixth sense working as I got students thinking of this scene—a sixth sense, to monitor my scarfed student’s response, revealed, perhaps overtly, perhaps in a subtlety, in her face or eyes, in a stiffening or relaxing of her posture. At another point, I might bring up Muslims of means giving shelter to persecuted Christians fleeing other Christians in thirteenth century Spain. A Christian rabble was fleeing for their lives amidst sectarian violence, victims of Christian terrorists attacking other Christians. The persecuted were saved, for a moment, hidden, for a moment, by generous and brave Muslims. My sixth sense might prompt me to share this aside, while ready to abort, if discomfort or anger seemed dangerously high.

She listens, and as important, her classmates listen, and listen to her listening, and listen to each other listening: tactile truth, truth from the trenches, grips and releases.

[1] That’s a lesson from Fear and Trembling. Or so I argue in On Soren Kierkegaard: Dialogue, Polemics, Lost Intimacy, and Time.

[2] See Robert H. Richardson, Jr., Emerson, The Mind on Fire, University of California Press, 1995, p. 312.

[3] Love Poems from God, Daniel Ladinsky, Penguin, 2002, p.9.)

[4] My sense of tactile truths and the limits of philosophical theory owe much to Wittgenstein, who provided what he called “perspicuous representations,” vivid and telling pictures of things, as a way to get insight into our how our lives and words work when we are away from philosophy’s abstractions and theories that so often float far from the playing fields of life.

[5] Cavell, Companionship, and Christian Theology, Oxford, 2011.

[6] See Gilian Rose, Love’s Work, New York Review Books, 2011.