Jolyon Baraka Thomas

Few people would think that the essence of Japanese religion could be encapsulated in an advertisement for antivirus software, but then again few people outside of Japan have seen this:

Obviously there is a lot going on in this video. Despite what I said above, I do not really think that there is an ahistorical “essence” to Japanese religion that the ad captures, but I do believe that its playfulness elucidates an aspect of religiosity in contemporary Japan that is worthy of serious attention. Let me first provide a little background before I explain what I mean.

Contemporary Japan presents a conundrum for the scholar of religion. On the one hand, a yearly cycle of festivals, memorial services, and purification rites provides one of the basic rhythms of Japanese social life. Shrines, temples, and religious statuary are also ubiquitous, dotting the rural landscape and seamlessly blending into the infrastructure of the congested Tokyo megalopolis. On the other hand, very few Japanese people describe themselves as “religious,” and most do not mentally sort their ritual activities as “religious,” even if they participate in these activities at formal religious institutions such as Buddhist temples and Shintō shrines.

It is therefore quite difficult to talk about the religious nature of Japanese ritual practices and material culture in a way that takes Japanese individuals’ claims of non-religiosity seriously. However, recently I have found myself using two terms that I think help clarify how individuals engage in religious behavior without thinking of themselves as “religious” (or thinking of their actions or ideas as “religion”).

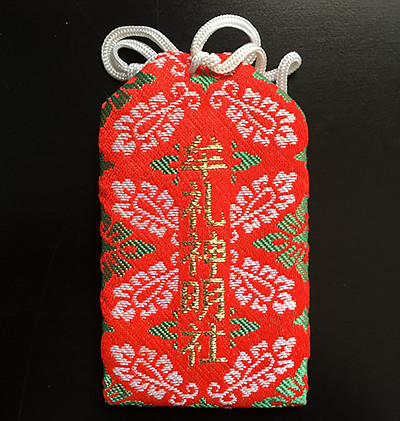

Just in case religion is ritual activity that is performed on the off chance that it might have efficacy even though the practitioner acknowledges that the action itself is inherently irrational. The practitioner of just in case religion thinks her practice is probably unnecessary, but she does it anyway. Just in case religion is a woman getting her car blessed by a Buddhist priest because she never knows if she might have an accident. It is the added peace of mind generated by visiting a shrine to petition the deities for success on an exam even though the petitioner studied as hard as she could. Just in case religion also has a material aspect. It is the talisman for safe childbirth that I noticed hanging on my friend’s kitchen wall while we were in the midst of a conversation about how he and his then-pregnant wife were definitely not religious. (To be fair, I’m one of the least religious people I know, but I do just in case religion, too. Here is the amulet I purchased on New Year’s Day 2013 at my local shrine as a little insurance policy that the rest of my dissertation research would go well.)

If just in case religion reflects the mild anxiety that something might go wrong, tongue in cheek religion reflects the anxiety that an outside observer might mistake one’s ritual behavior for being “really religious.” The practitioner of tongue in cheek religion mocks and parodies her ritual activity even as she engages in it. She knows that her actions look devout; she winks at her audience and flaunts this knowledge.

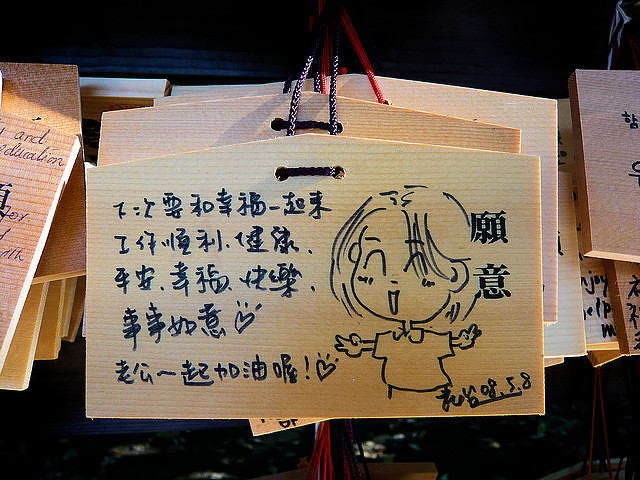

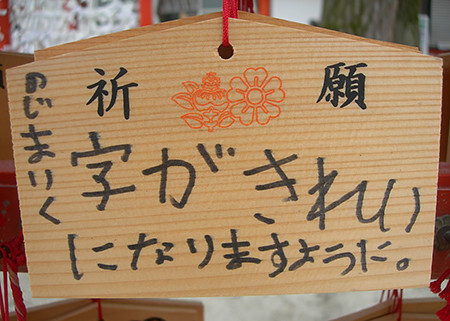

Her performed awareness of her behavior distinguishes her activity from (what she or others may see as) the unreflective, sheep-like actions of the pious. This performance allows the practitioner of tongue in cheek religion to laugh at religion but do religious stuff anyway. The practitioner of tongue in cheek religion is not an adherent. She is never a follower of tradition. She irreverently draws on tradition in bright, bold graffiti. Hers is the religion of a cosplay (short for “costume play”) performer who casually dresses up as a cartoon goddess or temporarily assumes the ritual gestures of a fictional priest. It is the religion of a fan who draws the fictional character Sailor Mars on a votive tablet (ema) at Hikawa Shrine 氷川神社, the real-world model for the homophonous Hikawa Shrine 火川神社 that appears in the Sailor Moon anime series. It is the religion of a student who humorously petitions the deities at Heian Jingū for better handwriting in a sloppily scrawled votive tablet (ema).

These two types of religion—and the self-aware stance each adopts—are beautifully synthesized in a promotional campaign for Symantec’s Norton antivirus security software from late winter/spring of 2012, when the company advertised a protective amulet doubling as a USB memory stick in the unforgettable video embedded above. (Here it is again, just in case you want to watch it twice. Who doesn’t love that soundtrack?)

Norton’s 2012 campaign was clearly driven by profit, but the ad blends the mundane need for computer security with the value-added promise of divine protection (just in case religion). Simultaneously, the ad mocks itself by subversively parodying a staid religious ceremony (tongue in cheek religion). Solemnly suited individuals kneel and bow over their computers while a priest chants an intercessory prayer (kitō) before ritual offering trays piled with USB sticks. The ancient “god power” (English phrase in the original narration) of Japan’s myriad deities both sublimates and protects the base desires of the consumers depicted in the video: the otaku (geek) with his cathectic affection for 2D dream girls; the lecherous old man with a secret pr0n stash; the flirtatious bride taking a naughty trip down memory lane; the mature woman of intrigue and innuendo; the anime music fan with her illegally downloaded tunes; the gangster who engages in shady speculation and black market deals. The need for divine protection is intimately linked to human foibles and the vices of the age; the classical Shintō preoccupation with purity and pollution is mapped onto contemporary anxieties about computer security and viral infection.

Is any of this “really” religious? Not in the sense that it demands formal assent to propositional statements of belief. Nobody needs to recite a credo to take advantage of the “god power” on offer in the company’s brilliant gimmick, and nobody needs to convert anything except perhaps some file formats. The security Norton’s amulet offers is both the security of divine protection (the USB amulets probably really were blessed by a Shintō priest) and the peace of mind that one is not really “being religious.” While Norton’s campaign originated in corporate advertising rather than religious proselytizing, it shows how certain ritual activities and material objects allow people in contemporary Japan to have their nonreligious cake while munching away on easily digestible bits of religion.

In isolation, the concepts of tongue in cheek religion and just in case religion can only describe a fraction of Japanese religious life. But when they are juxtaposed with the formal religiosity offered by Buddhist temples, Shintō shrines, and lay-centric religious organizations (such as the so-called new religions and pilgrimage confraternities)—and when they are viewed in conjunction with the quasi-religious language of ethics associations, divination practitioners, spiritual therapists, and “power spot” devotees—these two terms actually cover a great deal of the Japanese religious field.

While there is plenty of religious activity in Japanese history and contemporary life that is staid, solemn, and sincere, the concepts of tongue in cheek religion and just in case religion are useful because they acknowledge that people regularly and repeatedly make tactical decisions about how to position themselves vis-à-vis doctrine, ritual, and tradition. The prudent foresight of just in case religion gives practitioners the opportunity to take advantage of the worldly benefits (genze riyaku) offered by Japan’s religious institutions without necessarily subscribing to their doctrines. The irreverent humor of tongue in cheek religion gives them a chance to play at religion without formally adopting a religious identity. Everybody benefits, and nobody has to be “religious” who does not want to be.

(Postscript: A grateful tip of the hat to Professor Stephen Covell and his student Eric Mendes of Western Michigan University for originally bringing the Norton USB video to my attention. The translation of the video and the discussion of “tongue in cheek” and “just in case” religion here is mine, but Mr. Mendes’s forthcoming MA thesis will offer a more detailed analysis of the Norton promotional campaign as part of a broader discussion of amulets in Japan.)

Jolyon Baraka Thomas is an A.W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in the Center for the Humanities at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he teaches courses in (or cross-listed between) Religious Studies, East Asian Studies, and History. His research covers topics such as the politics of religious freedom, religion and media, and relationships between religion, sex, and gender. Jolyon is also Editor of Asian Traditions at the Marginalia Review of Books. He can be followed @jolyonbt.