The Painful Process of Awakening: Harm and Healing in the Healthy Happy Holy Yoga Community

Nirinjan Kaur Khalsa-Baker

Birthing: Healthy Happy Holy Community

In 1969 countercultural youth, predominantly white Americans from Judeo-Christian backgrounds, began to practice Kundalini Yoga as taught by Yogi Bhajan aka Harbhajan Singh Puri (1929-2004). My parents, like the majority of those who came into the community at the time, were questioning social and religious norms and protesting the violence of the Vietnam War, racial segregation, and sexual discrimination. They were looking for ways to expand their consciousness without intoxicants, finding value and inspiration in the teachings of Yogi Bhajan which incorporated Sikh, Yoga, and Ayurveda practices to live a Healthy Happy Holy lifestyle. Many chose to live as Khalsa Sikhs, adopting new names, dressing in white bana and turbans, eating a vegetarian diet, with a mission to serve and uplift humanity. I was born into this community in 1978 at the Mahadeva Ashram in Tucson, AZ, where we lived with other like-minded practitioners as one large extended family. It was a cozy upbringing, waking up before the sunrise for daily sadhana practice, reciting Guru Nanak’s Japji, doing Kundalini Yoga, going to Gurdwara, and singing kirtan. (Khalsa 2012) Over the years the community grew, establishing Ashrams, Yoga Centers, Gurdwaras, and businesses around the globe dedicated to Healthy Happy Holy (3HO) living. A diverse multi-cultural community developed, guided by Yogi Bhajan’s motto, “If you can’t see God in all, you can’t see God at all.”

|

|

|

Figure 1: With mother and brother (left.) Mahadeva Ashram in Tucson, AZ (middle). On the cover of Kundalini Kriya yoga manual (Courtesy KRI) (right).

Awakening: Darkness and Light

“Is this the darkness of the tomb or the darkness of the womb?”

In 2020 the global community began awakening to stories of sexually abusive behaviors, manipulative tactics, and exploitative business dealings by Yogi Bhajan and community members, with those in the inner circle enabling abuses and silencing dissenting voices. Students have been grappling with the contradictions of the spiritual teacher who both abused his power and empowered women, proclaiming that “the day the woman will not be exploited on this planet, there shall be peace on this Earth” (Yogi Bhajan, May 9, 1971). People are now awakening to the sexism, misogyny, heteropatriarchy, and white supremacy that have bled through his teachings that purport respect and equality for all. Those in the first generation are now reckoning with the trauma that some of their children experienced being sent away at young ages to live with other families or to boarding school in India where many reported being beaten, neglected, always hungry, told that hardship would make them strong “leaders of tomorrow.” New revelations of abuse by teachers, guides, and leaders of the community continue to be brought to light, demonstrating a history of silencing. How does a community of practitioners, who have spent the past 50 years dedicated to spreading the light, move toward healing when there is so much darkness in the shadow?

It has been a complicated process for many to reconcile the benefits they have found through the Sikh and yogic teachings of sadhana (daily practice), simran (meditation), and seva (selfless service), with the hypocrisy of the teacher and apparent dysfunction in the community. The myth-making narratives and lack of transparency have left many disillusioned and searching for their own truth through a web of lies, secrecy, and denial. Many are questioning the authority of Yogi Bhajan, the authenticity of his teachings, and representations of Sikhi. They are recognizing the need to deepen research, education, and engagement with global yoga and Sikh communities.

While there are those who continue to embrace Sikhism and Kundalini Yoga as they grapple with the reality of abuse in their community, others continue to proclaim their loyalty to the teacher and the teachings, denying the abuse and calling it slander perpetrated by toxic people with negative agendas. The polarization, cognitive dissonance, and antagonism being experienced within the community echo the painful processes of uprooting structural and systemic abuses of power also happening on national and global scales. Though painful, the process is an essential one. Silencing, whitewashing, and “spiritual bypassing” only allow abuse to continue and history to repeat itself through a process of suppressing, disassociating, and forgetting.

To move toward healing, it becomes helpful to look at the complexities and nuanced realities of this community in turmoil, rather than reaffirm polarizing, monolithic narratives that either idealize or demonize the teacher, teachings, and each other. It becomes essential to acknowledge that what we refer to as the “community” consists of a diverse spectrum of current and former practitioners of Kundalini Yoga and/or Sikh Dharma with different levels of experience, commitment, agency, and registers of abuse. Rather than silencing dissenting voices, it is important to ask, what is the cost of being blinded by our own experience and deaf to the stories of others? By opening ourselves to the stories of one another we may be able to stop cycles of suffering to heal and transform what it means to be in community.

Listening: Stories of Abuse

“Telling the story is the prerequisite to justice. But for the story to matter, someone must be listening. It is not easy to listen…But it is worth it. Grieving together, bearing the unbearable, is an act of transformation.”

In January 2020, stories of Yogi Bhajan’s sexual misconduct, manipulation, and abuse became widely known through the publication of a memoir, Premka: White Bird in a Golden Cage by Pamela Sahara Dyson (aka Premka) who served as Yogi Bhajan’s “Secretary-General” or right-hand woman, (1969-1984). Her memoir details their complex relationship, that she loved him for bringing her to Sikhi and the Shabd Guru, and how her spiritual longing as a bhakti devotee in love with her teacher, manifested into a sexual relationship and a complicated abortion. Her narrative captures the spiritual quest of her generation and their Orientalizing attitudes that exoticized Indian people and culture, granted Yoga teachers enlightened status and overwhelming spiritual authority, making the devoted students ripe for abuse. She explains how from the beginning, Yogi Bhajan prophesized that those closest to him would stab him in the back, implanting the idea that anyone who spoke against him was slanderous and treacherous, full of doubt, duality, and negativity.

Although rumors had circulated for years about sexual impropriety, and at least two lawsuits had been filed against Yogi Bhajan in the ’80s, the book hit a “Me Too” moment in the 3HO community. It was believed at face value and was devastating to those who looked to him as a spiritual teacher and had devoted their lives to upholding the positive ideals and practices of Sikhi and Yoga that he preached. It caused many more women to come forward, including some of his secretaries and those from the second generation who reported being groomed into sexual relations with him as teenagers. The revelations also unraveled layers of communal abuse and neglect, particularly expressed by many of those in the second generation.

|

|

|

Figure 2: At three years old, boarding a plane with Yogi Bhajan and Secretary to live with another family in Los Angeles for a few months (left). Second-generation students at boarding school in India (middle and right).

In blog posts, private Facebook groups, Zoom Listening Tours, podcasts, and personal conversations, the second-generation, some now in their 50s, have been identifying the trauma they experienced being sent away as young children to live with other community members or to boarding school in India, some as young as five years of age. They felt abandoned and neglected, without sufficient nourishment, experienced corporal punishment, beaten by teachers who also encouraged and dictated a culture of bullying and abuse. Many are now parents themselves, coming to terms with the harm they both endured and inflicted, acknowledging how it impacted their development and growth. Still, they maintain close ties with their friends who they view as family and continue to fight for themselves and one another with love, compassion, strength, grit, and resiliency.

The depth and breadth of open-hearted sharing, listening, and acknowledgment of abuse by the second-generation has offered a wake-up call to the first-generation. Their ability to hold safe space for one another to cry and rage, and their willingness to admit wrongdoing and apologize for harm caused, offers a powerful model of how to acknowledge suffering, address complicity and stop cycles of abuse. Many first-generation parents continue to grapple with the stories of abuse in relation to their own positive experiences of the community, teacher and teachings. Some first-generation parents have asked for forgiveness, sharing their own pain, guilt, and regret, while others have denied any culpability or wrongdoing. The second-generation are now discussing what accountability looks like when some of their parents continue to hold fast to their loyalty to Yogi Bhajan rather than believe their own children, continuing to demonstrate patterns of “silence, denial, excuses, diminishment, gaslighting, defensiveness, and combativeness” (Rishi Knots blog). Their voices are finally being heard as the community leadership board has begun to pay for their therapy, the first step toward reparations and preventing further abuse.

Acknowledging: Cases of Abuse

In March 2020, the 3HO-Sikh Dharma Organizations created a Collaborative Response Team (CRT) to respond to the initial allegations of Yogi Bhajan’s sexually abusive behavior. They hired An Olive Branch to conduct a six-month investigation, interviewing those who experienced abuse at the hands of Yogi Bhajan (d. 2004) as well as those who wanted to defend his character because he “couldn’t defend himself.” This latter group attempted to silence the report because they held fast to their positive experiences with the “Master,” unable to acknowledge the abuse and blaming reporters of harm. Nevertheless, in August 2020, the report was published identifying 75 incidents of abuse by 36 reporters of harm, concluding that much of the alleged conduct “more likely than not occurred” (AOB report, 6). Those in the inner circle who were lauded for their proximity to Yogi Bhajan are now being implicated as complicit in enabling abuse.

Unfortunately, cases of abuse in the teacher-student (guru-shishya) relationship are pervasive. Yoga Scholar Amanda Lucia in her paper “Guru Sex: Charisma, Proxemic Desire, and the Haptic Logics of the Guru-Disciple Relationship” details how abuse is perpetuated due to the concomitant logic that views the physical nearness to the teacher as an “honor” and a “blessing” (979). Such logic “diminishes guru accountability and creates social relationships that are readied forums for sexual abuse” (956). She argues, however, “instead of pathologizing each new case of sexual transgression as a guru’s individual moral failure,” it is more important to address the underlying structures, circles of silence, and logics that perpetuate harm (981). The twisting of logics around dharma, karma, tantra, enlightenment, and emancipation has for too long been used to harm the vulnerable, ignore inequalities, enable injustices, and ultimately blame victims for their abuse. The discourse around Yogi Bhajan and his teachings have operated in such a way to perpetuate these systems of violence by deifying, fetishizing, and commodifying the teacher and teachings, by silencing and demonizing victims, and ultimately reifying the exploitative systems they purport to address.

How is a community to move forward from abuse when some are not even able to acknowledge the harm done? What does healthy change look like within communities centered around unilateral, unquestioned authority? Does it require that the institutional bodies be dismantled, reformed, or reimagined? Are there aspects worth keeping which are healthy and productive? Can they be separated from those that have been complicit in harming or enabling harm? We can move toward healing by understanding how communities such as the Catholic Church, Hare Krishnas (ISKCON), Buddhists, and Yoga communities, have responded to cases of abuse. By learning from the past, we can reimagine the future.

Reimagining: Restorative Justice, Reconciliation and Revolutionary Love

“Any social harm can be traced to institutions that produce it, authorize it, or otherwise profit from it. To undo the injustice, we have to imagine new institutions–and step in to lead them.”

Cases of abuse are not new. They are ancient. They are embedded in our individual psyches and collective consciousness. Experiences of abuse cause trauma on a cellular level, passed down epigenetically through our DNA over generations. How to break the cycles of abuse to heal ourselves, our communities, and our world? The critical turn towards healing and liberation from harmful systems is to uproot dogmatic authoritarianism, patriarchal silencing, and neoliberal individualism that for too long have profited off the vulnerable and perpetuated abuse.

The 3HO-Sikh Dharma community is now on the long path of healing the collective shadow through a process of Compassionate Reconciliation and restorative justice led by a consulting team Just Outcomes. Their goal is to create organizational structures for acknowledgment and accountability to heal and reimagine community. However, for this process to work, it requires that those in power, demonstrate transparency, a willingness to identify and stop abuse by listening and grieving with those who have been harmed, acknowledging the suffering caused, providing support and resources for healing, holding abusive people and enablers accountable, and dismantling harmful systems.

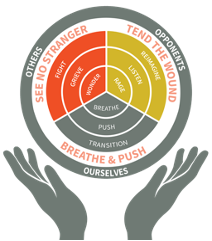

The process of restorative justice “opens up the possibility of [personal and political] reconciliation… ultimately founded only on the principle of forgiveness” (Kohen 399) which can liberate individuals and communities harmed by abuses of power. Political philosopher Hanna Arendt states that forgiveness frees “both the one who forgives and the one who is forgiven” (Arendt 240-41). While forgiveness allows for healing, Sikh activist Valarie Kaur reminds us that “Forgiveness is not forgetting. Forgiveness is freedom from hate. Because when we are free from hate, we see the ones who hurt us not as monsters, but as people who themselves are wounded…They’ve been radicalized by cultures and policies that we together can change” adding that “I had to tend to my own rage and grief first” (Kaur Ted Talk). Kaur offers “Revolutionary Love” as a way to reimagine institutions that have for too long caused harm. It opens a space for reconciliation and restorative justice by tending to our individual and collective wounds and extending love to others, ourselves, and even our opponents (Kaur 2020). Rather than holding on to hate and anger, or alternatively “spiritually bypassing” intense emotions deemed as “negative” such as grief and rage, these emotions have the productive possibilities of healing individual and collective suffering and transforming community when processed in safe spaces, through an ethic of love.

|

Figure 3: Revolutionary Love Compass (Courtesy Valarie Kaur, See No Stranger 2020)

The revolutionary call of love asks us to use a discerning mind and an open heart to fight for the dignity, safety, and sovereignty of all beings “free to grow within a mutually nourishing ecosystem” (Khalsa 2017, 246). By deepening education and engagement with diverse wisdom traditions and “post-lineage networks” we can reimagine what it means to be in communities and bodies that are truly healthy, happy, and holy.

Bio

Nirinjan Kaur Khalsa-Baker, Ph.D. is Senior Instructor of Theological Studies at Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles. She served as Acting Director of Graduate Yoga Studies (2019-2020) and Clinical Professor of Sikh & Jain Studies (2015-2018). Nirinjan Khalsa-Baker became a student of the Amritsari baaj (Punjabi percussion lineage) on the jori-pakhawaj in 2000 and was honored as its first female exponent. In 2014 she received her Ph.D. in Asian Languages and Cultures from the University of Michigan with a dissertation on “The Renaissance of Sikh Devotional Music: Memory, Identity, Orthopraxy.” Her scholarship, publications, and teaching examine Sikhi, Yoga, and the Dharma traditions through the lenses of history, philosophy, embodied practice, pedagogy, identity, gender, ethics, mysticism, and colonialism. Nirinjan currently serves as co-chair of the Sikh Studies Unit at the American Academy of Religion and as an editor for the Routledge journal Sikh Formations: Religion, Culture, Theory.