Daniel Anderson

Joel and Ethan Coen’s The Big Lebowski is 20 years old and Jerry Falwell Jr. blocked me on Twitter. These facts must be related.

Few things fascinate like the exasperating, delicious Hellscape of Twitter. Not only can anyone read the up-to-the-minute thoughts of our most accomplished, relevant, famous, and infamous minds, we can all “@“ them, provoking them to respond, belittle, ignore, or block us (like my own interactions with Jr. Falwell). The gap between great and small has seemingly collapsed, as the prophets of postmodernism promised it would.

It’s liberating and democratic, in all the best and worst ways. At its best, Twitter’s platform gives marginalized people a megaphone that extends the reach of their voices. Those newly empowered voices subsequently become a lifeline for the dispossessed and alienated, who gather together, finding a long-sought community. And who among us has not experienced an exhilarating solace in finding a group of like-minded individuals who would probably be great friends if not for geography?

The great downside of this environment is the echo-chambers that naturally grow from communities founded on like-mindedness. Any social group develops rules, discourses, and moral certainties that become shibboleths for full membership. Pierre Bourdieu developed much of his sociological analysis around the term “habitus,” using it to argue that these in-group cultural habits eventually determine the shape of members’ new ideas and expressions. Though Bourdieu’s ideas are sometimes seen as overly deterministic, a brief excursion into social media seems to at least partially validate his view of human social interaction.

Watch almost any group of True Believers long enough on Twitter and you will see a vitriol that only emerges from the moral certainties of religious Fundamentalism that we mistakenly believe is passé. By no means are we finished with fundamentalism. In our digital world, everyone is a Black Bible Evangelist, firing shrapnel at the wicked with a sacred canon. It comes out in the tone. Moral certainty overwhelms mercy.

On its 20th anniversary, it seems to me that The Big Lebowski has much to teach us about these matters. The Coen’s postmodern noir-comedy has inspired celebratory festivals all over the world and even an official religion: Dudeism. What work of art could better explain Twitter?

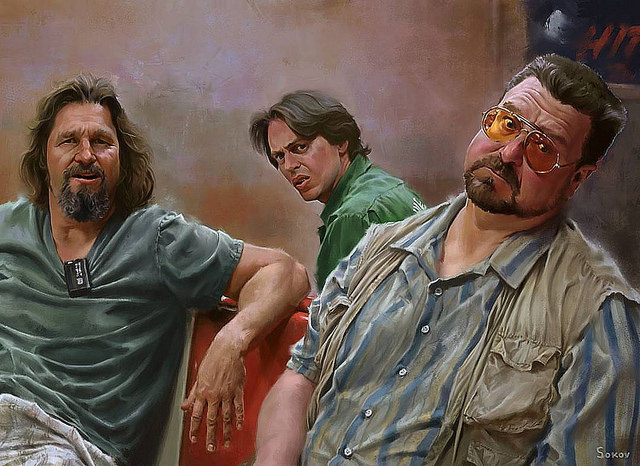

The secular Trinity of Joel and Ethan Coen’s cult classic can help put some flesh on this. There’s the Dude, of course, star of the show. In the non-kidnapping plot he stumbles into, he understands just enough to be confused. As a result, he floats with the plot’s tide, trying his best to simply live and let live. Perhaps this is why the film’s narrator, The Stranger, deems him the man for his time. At the End of History, as Francis Fukuyama framed the post-Soviet era, what else could a hero do but live and let live? Avoid the music of the Eagles, yes, but go with the flow of this new, post-political era. This was fine for 1992 (when the film was set), but the Dude’s willingness to allow outside information and events to determine his course makes him a bad fit for our time. Adjusting one’s thinking when “new shit has come to light,” is out of our current element.

Which leads us to Donny, who is constantly (and correctly) informed by Walter that is Out of His Element. And it’s true, the Dude struggles taking action, but he at least understands his environment. Donny, on the other hand, understands nothing. Throughout the movie, he seems incapable of even interpreting his surroundings at even the most basic level. The conversations he hears are baffling to him. “What’s Walter talking about Dude?” John Lennon or Vladimir Lenin? “I am the Walrus,” he nonsensically proclaims. No, Donny’s inability to follow a conversation keeps him safely innocent from our battleground of certainty.

That leaves Walter Sobchak, the film’s Old Testament God of Vengeance. Walter owns a security business, is a war vet, and dresses like one. It’s his glasses that are important though. The yellow-tinted aviators. All of the world is filtered through these glasses, giving the world of variety a monochromatic, sickly, yellow tint. He does not even see the world in black and white, only this yellow, and this makes him an ideal model for our own social media avatars.

Whereas Donny is unable to even perceive the conversation, and the Dude understands only enough to be carried through the adventure, Walter imposes the yellow will of his certainty upon everyone around and forces them into the car to go along for the ride with a duffel bag of his dirty undies. “She kidnapped herself!” Thus, speculation about the spoiled behavior of a young trophy wife is contorted into Walter’s grand narrative of the Vietnam War, and he forces himself into the drama, fully confident that his perception is right.

Walter would have loved Twitter.

How much of Twitter’s discourse is composed of self-righteous proclamations of guilt, cruelty, or ignorance? Who among us has not wielded the power of the @ to bring to shame a politician, celebrity, or pundit who has violated our interpretation of the social contract? However cleverly, hiply, or saintly our Tweets are phrased, they are all one version or another of “OVER THE LINE!” And our callous indignation resembles nothing so much as Walter pulling a gun on poor Smokey and ordering him to “mark it zero!”

Yet the Twitter-warrior is not evil. Their monstrous justice is only a deformed image of a good intention. Likewise, it’s important to emphasize that despite his absolute faith in his perception of the world, Walter is not a villain. His fixation on Vietnam stems from actually having seen his buddies “die face down in the muck,” and therefore is grounded in true love and a legitimate interest in justice. His militaristic approach to all of life’s uncertainties is simply a natural outcome of the failure of the Vietnam War to establish peace. There is even a bravery to his vulgar quest to assist in Right’s victory over Wrong. His unwillingness to give in to the Nihilists and his skill in the parking lot battle is an exhilarating case of establishing the rule of law. The fight does, however, lead to the heart attack and death of beloved, innocent Donny, who loved surfing.

We are all Walter now.

Within our online huddles, we are each (to some degree at least) formed by the beliefs and rituals of our partisanship. We emerge, fully formed in our moral certainty, to throttle apostates into submission. Of course, the only thing we really accomplish is to validate our ideological enemies’ own assumptions. We merely step on the throttle of partisanship as we huddle deeper and more tightly into our echo chambers. But the performance of our correctness is its own reward.

To point out specific examples of Sobchakian Twitter would be merely perpetuating the destructive ecstasy of its call-out-culture. But each of us who defends our trenches in the theater of social media knows when we have threatened our adversaries with “a world of pain,” hurled bowling balls into their abdomens, and quipped about the ease of obtaining a human toe.

Perhaps the Stranger was right about the Dude; maybe he was the man for his time. That time has passed however, and we now most certainly live in the Age of Walter.

Daniel Anderson is Assistant Professor of English/Fine Arts Department at Mount Aloysius College where he teaches a range of Rhetoric, Literature, and Film classes at the Mount, including classes on the Jewish American Novel, Flannery O’Connor, Shirley Jackson, Franz Kafka, the Literature of Pittsburgh, and the Classic Horror Film. He also produces and hosts the Sectarian Review Podcast, which investigates art, culture, politics, and religion.