Jill Marshall

Last year, David Bowie surprised us all by dying. To his fans, it was incomprehensible that Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane, or the Thin White Duke would die. But even more so, it was surprising because he had released an album, “Blackstar,” just two days before his death. After his death, the album took on heightened significance as a work of art produced as he was facing death. Fans consoled themselves with clues about Bowie’s life and death hidden in the lyrics, the videos, even the album artwork.

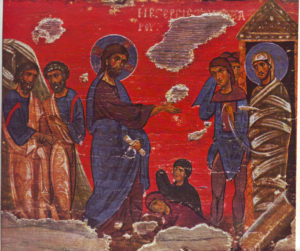

With its opening line, “Look up here, I’m in heaven,” the song “Lazarus,” the second single from the album, draws attention to the timing of its creation and release during the artist’s terminal illness. The title of the song draws inspiration from the story of Lazarus, whom Jesus raises from the dead in the Gospel of John. In the history of interpretation, Lazarus has signified Jesus’s salvation of humanity: He overcame death in a very real and physical way. The weight of interpretation most often falls on Jesus’s actions of raising Lazarus and giving him new life—a story that seems unequivocally positive.

Darker currents, however, have surfaced in the interpretation of Lazarus’s story, in which the weight is on Lazarus’s silence and death. The silence of Lazarus creates a narrative lacuna that artists have used to explore experiences of suffering and death. Two rock songs in the last ten years have developed these currents: Bowie’s “Lazarus” (2016) and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’ “Dig Lazarus Dig!” (2008). In the former, Lazarus becomes another character in the long line of Bowie rock personas. He represents the challenge of death and vividly signifies the transition from life to death. For Cave, Lazarus is a liminal and miserable character, in large part because he had no choice: He didn’t ask to be raised from the dead. Both artists contemplate death, choice, and freedom through the figure of Lazarus.

* Lazarus in the Gospel of John *

In John 11–12, Lazarus is silent. Throughout his resurrection and its aftermath, everyone is talking about what happened to Lazarus—first his sickness, then his death, finally his resurrection—except Lazarus himself. This silence invites interpreters to fill in Lazarus’s point of view: Bowie can say “Look up here, I’m in heaven,” and Cave can question whether Lazarus would want to be raised from the dead.

The narrative begins with the identification of Lazarus of Bethany and his sisters, Martha and Mary, all of whom Jesus loved (John 11:5). Lazarus is sick, so the sisters send Jesus a message, “the one whom you love is sick” (11:3). Jesus, however, does not immediately go to Bethany. He knows that “this sickness will not lead to death, but to the glory of God” (11:4). After waiting two days, he decides to go to them, but he already knows that Lazarus is dead (11:14). As he is traveling with his disciples, Martha meets him on the road, while Mary stays at home with the mourners. Martha says, “Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died” (11:21). Their conversation leads to Martha’s confession in Jesus as “the resurrection and the life.” She returns to Mary, and tells her that Jesus is calling for her. Mary then goes to meet Jesus on the road, says the same thing, “If only you had been here, my brother would not have died,” and weeps at his feet (11:32). Mary’s grief moves Jesus to tears in that famously short verse, “Jesus wept” (11:25). They go to the cave where Lazarus is buried, and Jesus tells them to remove the stone that covers the entrance. Martha, ever the practical sister, objects: “Lord, there will surely be a stench now, for it has been four days” (11:39). After Jesus questions Martha’s belief, they remove the stone. Jesus prays and cries, “Lazarus, come out!” (11:43).

Then, after all of this talking about Lazarus—about his illness (11:3–4), whether he is asleep or dead (11:11–14), whether he would have lived under different circumstances (11:21, 23, 32), how much Jesus loved him (11:3, 5, 36), and where and how long he was buried (11:36, 39)—Lazarus emerges, yet still does not speak.

The man who had died came forth with his feet and hands bound in linens, and his face was wrapped in a cloth. Jesus said to them, “Unbind him, and let him go.” (11:44)

This miracle is the last one performed by Jesus in the Fourth Gospel. It causes some people to believe (11:45), but the chief priests and council feel threatened by Jesus’s miracles and plot to kill him. This event, therefore, begins the movement to Jesus’s execution. Lazarus is pivotal.

In the aftermath of Lazarus’s resurrection, people continue to talk about him, yet he has nothing to say about his experience. The siblings host a dinner, where Martha serves and Lazarus reclines with the disciples at the table. Mary, in a symbolic reversal of the stench of the tomb, spills expensive perfume on Jesus’s feet and anoints him, just as women in the ancient Mediterranean anointed dead bodies (12:1–3). A large crowd comes to Bethany when they find out he is there, “and they came not only for Jesus, but also so that they could see Lazarus, whom he had raised from the dead” (12:9). Jesus isn’t the only one whom the chief priests seek to kill: They also plan to kill Lazarus (12:10). After Jesus enters Jerusalem for the last time, riding on a donkey and celebrated as king (12:12–13), the people are still talking about Lazarus: “The crowd, who were with him when he called Lazarus out of the tomb and raised him from the dead, continued to give witness.” (12:17). Controversy swirls around Lazarus, even though he has not said or done anything.

We don’t know what happens to Lazarus after this. He drops out of the story as John zooms in on Jesus, his death, and resurrection. The first resurrection recedes into the background.

* Bowie’s Lazarus Dead *

In “Lazarus,” David Bowie speaks from the dead:

Look up here, I’m in heaven

I’ve got scars that can’t be seen

I’ve got drama can’t be stolen

Everyone knows me now

If we hear this in terms of the biblical story, Bowie speaks as Lazarus. This stanza fills in Lazarus’s perspective in the post-death and pre-resurrection moment in which the family is interacting with Jesus—the moment at which Lazarus is most absent and silent (and dead). In the Gospel, the activity takes place around the tomb, but Bowie takes the next step: Lazarus has moved from the tomb to heaven. With the next two lines, Bowie picks up on key details of the biblical story: The “scars that can’t be seen” recall Lazarus’s illness and his body wrapped and stinking in the tomb. The lyrics about “drama” and “everyone knows me now” echo the conflict and fame that adheres to Lazarus after the miracle. In the Gospel and Bowie’s interpretation of it, the act of coming back from the dead is dramatic and controversial.

Two days after the release of the record, however, these verses sound different. Now, Bowie himself asks us to “Look up here, I’m in heaven.” He has passed away. Throughout his career, he was a master of creating characters and blurring the boundaries between them and himself. Tragically, he once again becomes his character: Rather than Aladdin Sane, he is Lazarus Dead. The “scars that can’t be seen” are the effects of his cancer that the public knew about only after his death. “Everybody knows me now”: What was hidden at the time of the album’s release is now clear to those who hear.

Bowie’s art—and his biblical interpretation—does not stop at his songwriting. The music video for “Lazarus” complements Bowie’s lyric interpretation of the Gospel Lazarus. The video begins with an antique wardrobe, a visual echo of Lazarus’s tomb. A shadowy figure emerges from it, fingers first. As Bowie begins to sing, he is in a single bed in what looks like a hospital. The camera closes in first on his hands, the part of the human body that seems to age the fastest, with thin skin and dark veins. A bandage encircles his face, much like Lazarus, and buttons cover his eyes, recalling the ancient Greek practice of placing coins on the corpse’s eyes to pay for their passage to Hades across the River Styx. A woman (death personified?) lurks under the bed, and as she reaches up to him, he begins to hover over the bed. He is in between, in transition.

A second, more familiar Bowie appears when he sings, “By the time I got to New York, I was living like a king.” This Bowie dances and writes frantically—no bandages, bed clothes, or blankets. Bowie called New York home for the last twenty years of his life.[1] In this time, he was married and moved beyond the spectacle and controversy of his early career. In the video, he alternates between dancing and writing frantically. He takes out the pen, which looks like a syringe, and dramatizes the intensity of his writing process. He cringes, looks enlightened, hunches over the desk, and writes until the roll of paper ends. All the while, a skull sits on the desks, signifying death’s presence even as Bowie is at his truest—creating and entertaining. This is the Bowie, not the bandaged one in the bed, who slinks into the wardrobe at the end of the video. The woman under the bed never touches him. “You know I’ll be free,” he says. The writing that he did in the last years or months was freeing, as death can be. “Now ain’t that just like me.” He anticipated what we would all say about him: Of course he would go out creating.[2]

For those with terminal illness, death can be a drawn-out process. Bowie captures the sense of danger, the scars seen and unseen, the effects of medication (“so high, it makes my brain whirl”), and the break between who you are and what the illness makes you. The transition between death and life is fraught, and Bowie understands Lazarus in these terms. Lazarus represents the danger of death, and, at the same time, the chance to define how one dies. Lazarus was ill, his corpse reeked after four days, but he lived and died as someone loved.

* Cave’s Poor Larry *

=

About eight years before David Bowie’s “Lazarus,” Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds released their take on the once-dead friend of Jesus in “Dig, Lazarus, Dig!” Cave imagines Lazarus’s response to his newfound life. Like Bowie, Cave emphasizes the transition from death to life. But here, Lazarus is stuck between the two.

Cave is no stranger to theological themes. His songwriting displays his fascination and horror with biblical stories and images. Most famously, the song “Mercy Seat” applies the throne of God imagery from the Hebrew Bible to American capital punishment by electric chair.[3] He peppers the entire “Dig Lazarus Dig!” album with biblical and classical allusions. On the Bad Seeds’ website at the time of the album’s release, Cave explained his view of Lazarus:[4] “Ever since I can remember hearing the Lazarus story, when I was a kid, you know, back in church, I was disturbed and worried by it. Traumatized, actually. We are all, of course, in awe of the greatest of Christ’s miracles—raising a man from the dead—but I couldn’t help but wonder how Lazarus felt about it. As a child it gave me the creeps, to be honest.” Cave explicitly shifts focus from Jesus’s action to Lazarus’s missing point of view. In the song, he relocates Lazarus to modern New York and fuses him with Harry Houdini, whom Cave calls “the second greatest escapologist,” second only to Lazarus—hence, the nickname “Larry.”

The chorus, repetitive and raucous, introduces Lazarus’s reluctance and in-betweenness: Perhaps Larry would prefer to be dead, to dig himself back into the grave:

Dig yourself, Lazarus!

Dig yourself, Lazarus!

Dig yourself back in that hole

Cave moves back and forth from narrating Larry’s post-resurrection story to speaking as Lazarus caught between death and life. For Lazarus, life after resurrection starts well enough. He makes his home “in the autumn branches” and enjoys good company. But then he begins to wander from place to place in search of something—“Well, New York City, man, San Francisco, LA, I don’t know.” He is insatiable and self-destructive: He indulges in drugs (in San Francisco, he “spent a year in outer space”), women (“He feasted on their lovely bodies like a lunatic”), and guns (“He stockpiled weapons and took potshots in the air”).

At points in Cave’s sing-speak narration, he speaks as Lazarus. Two statements suggest that the resurrection has left him in an in-between, part-here-part-there state of existence. First, “I can hear my mother wailing and a whole lot of scraping of chairs. I don’t know what it is but there’s definitely something going on upstairs.” Larry wakes up and hears people mourning above him. Cave questions Lazarus’ knowledge of and acquiescence to what happened to him: As he wakes from the dead, he doesn’t know what is going on “upstairs.”

Second, Lazarus again questions what is going on “upstairs”: “I can hear chants and incantations, and some guy is mentioning me in his prayers.” In the biblical narrative, Jesus prays before he utters the statement that produces the miracle, “Lazarus, come out!” In Cave’s retelling, Jesus is “some guy.” Lazarus is again portrayed at the moment of miracle. He is disoriented when he hears the mechanisms of the miracle, which result in his being awake, alive, and able to hear.

Lazarus’s wandering and dissatisfaction after his resurrection ultimately has a sad ending. He ends up homeless, “in a soup queue, a dope fiend, a slave, then prison, then the madhouse, then the grave.” The tragic ending occurs because his renewed life was not his choice.

I mean, he, he never asked to be raised from the tomb

I mean, no one ever actually asked him to forsake his dreams

Anyway, to cut a long story short, fate finally found him

In other words, sometimes death is acceptable, and even preferable if the choice is between death and an unlivable life. The reference to fate suggests that since Lazarus avoided death, he had a debt to pay. The delay of death did not mean that Larry would not die. And, since he had already experienced sickness and death, he knew what would come for him in a way that the rest of us do not. Poor Larry.

For Cave, the moral of the story comes in a final question: “But what do we really know of the dead, and who actually cares?” How can we say that Lazarus is better off alive? What do we know about what he senses or experiences while “dead”? And aren’t human beings actually more destructive to themselves and to others than death will ever be?

* * *

The Lazarus story in the Gospel of John is at once hopeful and haunting. It is haunting because the central character never speaks, leaving a narrative lacuna—what does he think about his death? Does he want to be raised from the dead? Does his impending second death frighten him or provide him an opportunity for self-redefinition? In these two rock songs, the artists gravitate to the character’s silence and craft new personas for Lazarus that incorporate aspects of themselves—their experiences of fame, illness, fear, and death. Lazarus is once again resurrected in their interpretation: this time as a rock star, escapologist, and someone grappling with death.

[1] http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/17/fashion/david-bowie-invisible-new-yorker.html

[2] http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/david-bowies-death-a-work-of-art-says-tony-visconti-20160111

[3] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ahr4KFl79WI

[4] http://www.nme.com/news/music/nick-cave-and-the-bad-seeds-43-1351551

Jill Marshall completed the PhD in Religion from Emory University. Her research focuses on women’s activity in early Christianity and the reception history of people and places in New Testament texts.