Mark Hulsether

On the day that Prince died I heard about it as breaking news on a country music station in the middle of Indiana. When I tuned into CNN en Español on my satellite radio, the programming was about reactions in Latin America. Soon the Eiffel Tower was bathed in purple light, thousands marched in a New Orleans-style funeral procession, and President Obama played “Purple Rain” at the British embassy. In Minneapolis—Prince’s hometown and my own—there was an effort to declare purple the official state color and Prince accounted for a large proportion of news reports for days. Anyone from Minneapolis who cares about popular music can tell you about life-changing experiences at the venue that Prince largely built, First Avenue—famous as the setting for his film Purple Rain, which at one point in 1984 accounted for the nation’s top single, album and film. Even in the nearby outpost of rural Northern Wisconsin where I spend my summers, the local newspaper interrupted its round of obituaries and high school sports news to reminisce about Prince, recall his visits to a local religious camp as a teen, and debate whether his music had remained sufficiently interesting after his Sign O the Times record in 1987.

Even now, more than a year later, shock waves of grief are reverberating. Scholars organized major international conferences at Yale last January and at the University of Salford this month. I spent much of my day on Friday April 21 watching a stream of Prince videos on MTV Classic. For the most part these were not even his best videos, yet they went on and on for hours with almost no repetition, and true landmark songs kept popping up just when I thought surely the rotation would start over: “When Doves Cry” at the ninety-minute mark, “Sign O the Times” in the second hour, “Little Red Corvette” in the third hour, on and on.

Simply stated, Prince had wider synthetic reach and more astonishing virtuosity than almost any other musician of our time. As the New York Times noted, “he was admired well-nigh universally” for music that was “a cornucopia of ideas: triumphantly, brilliantly kaleidoscopic.” The question is not whether he fits, but where, in a list of the greatest American musicians—jockeying with Bob Dylan or John Coltrane for a top slot or matching Duke Ellington and Joni Mitchell in range and innovation.

Among this select group, few had deeper spiritual-religious interests and cultural impacts. It is essential not to pigeonhole Prince as a mere icon of sexual partying—whether to celebrate this or not—as opposed to a musical genius who also voiced a wide range of concerns including community-building, social justice, and joyful transcendence.

Now, it is certainly true that Prince’s road to fame included branding himself as a sort of sex god. More pointedly, it would be possible to cherry-pick a selection of his raunchiest lyrics, most conservative end-times beliefs spinning out from his Adventist upbringing and mature years as a devout Jehovah’s Witness, and least innovative pop grooves—and then accentuate the negative about its cultural effects, both religious or otherwise. Like Dylan before him, Prince’s output included both immensely formidable classics and other songs that are better forgotten. In the case of both Prince and Dylan, simply to accentuate the negative is to risk missing some of the most profound spiritual creativity of our generation. No one was more important than Prince in rearticulating—through the genius of his music—what the terms “spirituality” and “sexuality” would mean in relation to each another and to emergent racial formations.

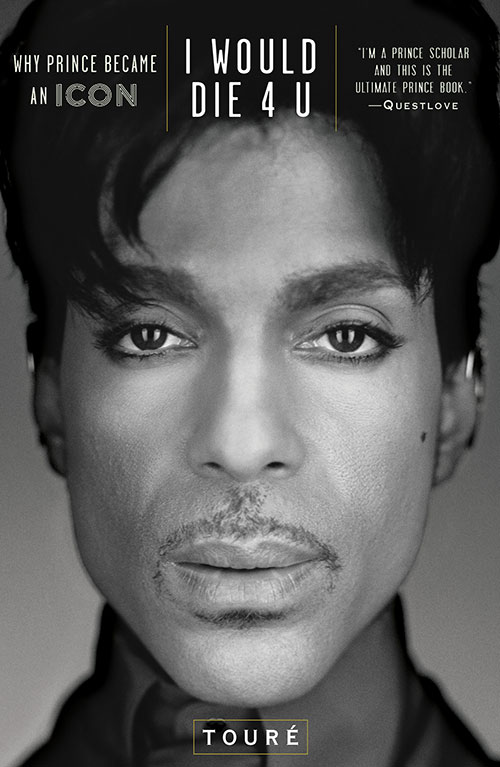

In a thoughtful book on Prince, Touré notes that he was born at an auspicious time to synthesize a wide range of music from the baby boom generation, yet also to articulate emerging concerns of youth coming of age during the 1980s. For example, Touré points to the rising prevalence of divorce and latchkey kids with reduced parental guidance due to two-earner families. Prince’s relationship with his parents was rocky, and this likely accounts for the haunting, yearning chorus of one of his masterpieces: “How can you just leave me standing/Alone in a world that’s so cold?….This is what it sounds like/When Doves Cry.”

In a thoughtful book on Prince, Touré notes that he was born at an auspicious time to synthesize a wide range of music from the baby boom generation, yet also to articulate emerging concerns of youth coming of age during the 1980s. For example, Touré points to the rising prevalence of divorce and latchkey kids with reduced parental guidance due to two-earner families. Prince’s relationship with his parents was rocky, and this likely accounts for the haunting, yearning chorus of one of his masterpieces: “How can you just leave me standing/Alone in a world that’s so cold?….This is what it sounds like/When Doves Cry.”

Like many other critics, Touré flags Prince’s preoccupations with eroticism and spirituality. Early in his career, he made a name for himself through equal parts musical virtuosity and pushing people’s buttons around sex. If you were a conservative on family values in these years, or even a card-carrying feminist fighting on the anti-pornography team of the “sex wars” that racked 1980s feminism, Prince was one of your sworn enemies. Among the few who rivaled him was Madonna—and much of her work that redirected cultural scripts from sex and spirituality in zero-sum conflict to a fusion of sexual and spiritual transcendence, was actually a popularization trickling down from Prince’s more innovative and profound creativity.

Meanwhile, if you fought on the sexual liberation side of the feminist sex wars—stressing gender fluidity and harnessing erotic desire to break down hegemonic forms of sex/gender expectation—Prince was your hero and part of the soundtrack of your life. And I will risk another claim: cutting edge works in feminist religious thought such as Carter Heyward’s, which became a root of today’s queer spiritualities, were also in significant degree trickle-down effects from the sensibilities Prince articulated. Over time he increasingly blended such ideas—sometimes using coded language—with fairly orthodox themes from African-American Christianity and end-times beliefs learned during his Adventist upbringing.

Thus if we could weigh Prince’s influence solely as a creative religious innovator, abstracting from his music, he would still rank as a major force in popular Christianity—although we cannot actually abstract this way since his intervention was through music. If we solely read Prince’s words about his “New Power Generation” and its inclusive spirituality called “lovesexy,” the words can sound rather lame. Nor is it easy to say whether all the parts completely cohere conceptually. The evangelical magazine, Wittenberg Door, called his album Lovesexy a “disgusting, egotistical collection of theological gibberish” setting out “to prove that God… [is] a sex maniac.” But Prince’s lyrics alone carried relatively little of his total vision, and could even detract from it. If you listened with open ears, you were quite likely to discover that you had become a sort of believer. Do you doubt that songs like “Purple Rain” or “Anna Stesia” (the centerpiece of Lovesexy) can be powerful articulations of Christianity? Don’t scoff until you’ve listened carefully.

There is much more worth saying about Prince’s life and legacy than can fit in one Sacred Matters article. For example, we could discuss his addiction to opioid painkillers. Here we should push back against commentators who seem self-satisfied to know little else about him—just another rock star dead from an overdose—nevermind that he was famous for a remarkably intense work ethic and squeaky-clean stance toward recreational drugs (Drummer Questlove of the Roots even recalls Prince making him pay $20 into a curse jar for saying the word “shit” during a recording session, despite Questlove’s protest that Prince had been the one who taught him to curse.)

We could discuss Prince’s brilliant collaborations with Mavis Staples and Patty LaBelle—to a large extent neglected due to Prince’s conflicts with Warner Brothers Records—featuring pointed commentary about making Christianity welcoming for a “New Power Generation” that presupposed sex-positive, queer-friendly, and racially-progressive spiritualities.

We could discuss the last song Prince released, “Baltimore”—a sadly under-appreciated contribution to public discourse about the Black Lives Matter movement (a cause which Prince strongly supported as a philanthropist). What lingers from “Baltimore” is its echoing chant—“If there ain’t no justice then there ain’t no peace”—presented with an extraordinary balance of common sense assertion, protest, and cautious open-hearted hope.

And of course we could discuss Prince’s relative turn toward overt spirituality and “positive” messages—which, in truth, were always present in his music but (as Questlove discovered) came forward more explicitly in his later career. At no point did Prince ever apologize for celebrating sexual pleasure—and doing so with greater playfulness, commitment to mutuality, and androgynous sensibilities than almost any pop musician of his day—but he did broaden his vision, back away from some of his early branding, and clarify how adding sex to any relationship is playing with fire: it makes good relationships better and bad relationships worse. For example, in Purple Rain, his libidinous “Darling Nikki”—which famously provoked Tipper Gore to lobby for parental warning labels on records—is used to lash out at the “Nikki” character for a perceived betrayal, accused in the context of the film as prostituting her lustful proclivities to make a buck. In the film this conflict is resolved. Nor does this come close to the film’s most dark and disturbing themes: Prince’s father killing himself and Prince nearly following in his footsteps. The key point—whether we are speaking of dysfunctional forms of sex, AIDS, racism, or despair—was to face such demons and triumph, as distilled in Prince’s signature “Purple Rain,” which features gospel style, a theology of grace, and one of the greatest guitar solos ever recorded.

As already noted, we cannot cover everything that’s sacred in Prince’s music here. So let’s simply pause and appreciate some of Prince’s music. Where better to focus than “Purple Rain,” which came to be part of the lingua franca of a whole generation?

Here is a mass choir of high school kids singing it.

Here is Bruce Springsteen singing it.

Here is Tori Amos singing it.

Here is Dwight Yoakam singing it.

Anyone who Googles “purple rain cover versions” and follows the links will see that this list could go on almost indefinitely— long enough that MTV Classics’ retrospective could conceivably have been only covers of “Purple Rain.”

And of course a long stretch of this hypothetical playlist could simply be a range of Prince’s own versions. Let us close with my personal favorite: the greatest musician of his generation, playing his greatest song, on the largest stage in the world. And in the rain, no less. If music or group religious rituals can change the world—and I think at times they can—then the world changed during this performance.

Rest in peace, Prince.

Mark Hulsether is Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Tennessee whose research centers on the connections between culture, and society in recent US history. He is author of Religion, Culture, and Politics in the Twentieth Century United States (Columbia University Press 2007) and Building a Protestant Left: Christianity and Crisis Magazine, 1941-1993 (University of Tennessee Press 1999).