Judith Weisenfeld

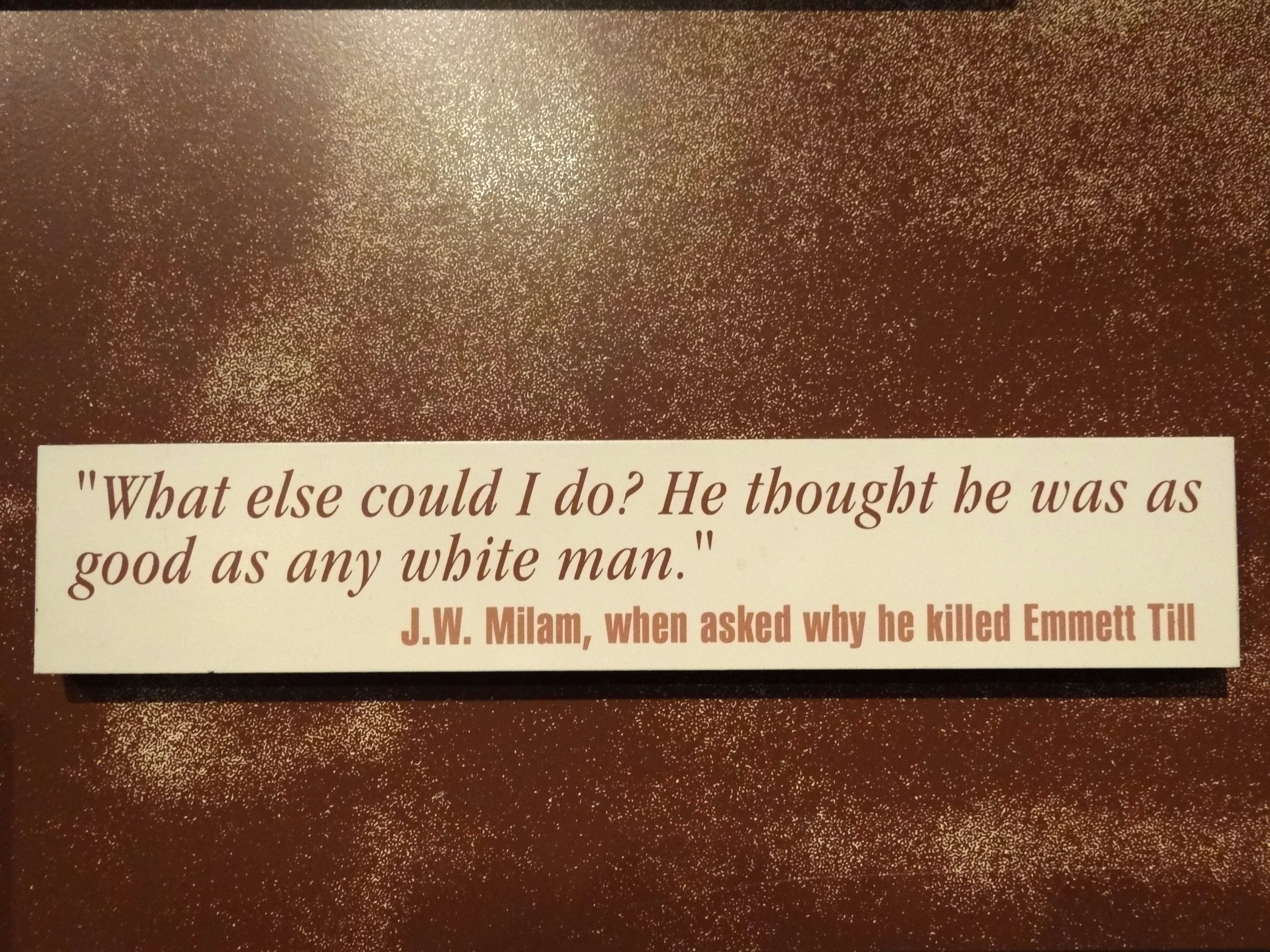

Emmett Till’s casket lies in a room set apart from the open galleries in the section of the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) devoted to exhibits on “Defending Freedom, Defining Freedom” during the era of segregation. The visitor’s map designates the room a memorial, another way in which it is distinguished from the museum’s work of public history and cultural interpretation. On the wall outside the memorial room is an exhibit telling the story of the 14-year-old Till’s kidnapping and murder in Money, Mississippi in 1955 by two white men, Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam. Till had transgressed the unwritten codes of white supremacy’s racial hierarchy by interacting with Bryant’s wife, Carolyn, in the Bryants’ grocery store. Bryant and Milam, who later admitted that they had murdered Till, were acquitted by an all-white, all-male jury after a little more than an hour’s deliberation. The museum’s display includes the September 15, 1955 issue of Jet magazine that featured photographs of Till’s body, his face distorted from a beating, the bullet hole visible in his temple, and his body bloated from having been submerged in the Tallahatchie River, weighted down by a cotton gin fan. Mamie Till Mobley, Till’s mother, had insisted on an open-casket funeral, calling out, “Let the people see what they did to my boy.”

Till’s family donated the casket to the NMAAHC in 2009, seeking to preserve the item after Till’s body was exhumed from Chicago’s Burr Oak Cemetery when the investigation into his murder was reopened in 2005. Of the decision to donate the casket, Simeon Wright, Till’s cousin who was asleep in the same room the night Bryant and Milam came and took Till away, commented that, “Some people would say this is just a wooden box, scuffed up on the outside and stained on the inside. But this very particular box tells a story, lots of stories. And by sending it to the Smithsonian’s African-American museum we – Emmett’s few remaining relatives – are doing what we can to make sure those stories get told long after we’re gone” (Smithsonian News Release, August 27, 2009). As the plans for the museum took shape, director Lonnie G. Bunch III and the curators worried about the propriety of displaying the casket, but ultimately decided that this material reminder of the brutality of white supremacy would be an important part of the institution’s interpretation of American and African-American history.

The visitors who passed through the memorial on the Wednesday afternoon in October when I visited were quiet and reverent as they stood before the white silk-lined pine box that had held his body or sat on a pew at the back of the small room. I was surprised and moved by the fact that it is so small – not the shockingly small size of an infant’s casket, but not that of an adult – and could not help but think about the promise of life ahead of him taken away by those men who were so invested in racial dominance. I found it difficult to stand there for long, with the casket and all it represents the sole focus of attention.

When I left the Emmett Till Memorial room I paused for a moment to ask Wanda L. McClary, the security guard whose task it is to prevent visitors from photographing the casket in accord with the family’s wishes, how she deals with the emotion of the visitors and of the memorial room itself. She told me that being there was “like going to a funeral every day” and that when the emotion mounts, “sometimes I have to pray it off.” Did she wish she were stationed somewhere else in the museum, I asked? McClary replied animatedly that this was her favorite place in the museum and she would not choose anything else. “It’s like being an usher at his funeral,” she told me, and emphasized a strong sense of duty and vocation in the work of safeguarding the casket and the family’s wishes. She told me she often says, “Thank you God for allowing me to be a part of history.”

Taken together, the display of the material artifact of Till’s casket, the work of interpretation in the memorial to his life, and McClary’s prayerful watch over the room highlight the expected and unexpected ways the NMAAHC features religion as part of the story of African-American history and culture. The museum’s curators and exhibit designers have attended to religion in varied forms and institutional contexts consistently throughout the three floors of History Galleries, and discussions of African-American religious life appear in the Community and Culture Galleries. The sheer amount of material culture on display in the museum in general and representing African-American religious life specifically is a powerful testament to black presence in America from its very beginnings. Exhibits on the floor focusing on “Slavery and Freedom, 1400-1877” present the material culture of religious life under slavery, often highlighting continuity of African traditions, as in the display of a cloth accompanied by pins, shards of glass, a cowrie shell, and buttons found under the floorboards in the attic of a house in Newport, Rhode Island and believed to be components of an nkisi, used by BaKongo people for power and protection. This section also features items such as a drum from the Sea Islands and glass beads from a burial site in Virginia, both representing connections to West and Central African religious practices.

The bulk of the material artifacts related to African-American religious history on display throughout the museum underscore the centrality of Christianity and churches to black life and culture. The exhibits bring to life the physical infrastructure of black churches and denominations through sections showing a church pew, money-box, and land deed from Richard Allen’s Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, dedicated in Philadelphia in 1794, to other parts of the museum featuring artifacts from Baptist and Methodist churches founded after emancipation and representing all regions of the country. A display case with a kneeler, votive candle stand, and information about the Sisters of the Holy Family and St. Augustine Roman Catholic Church in New Orleans points to the experiences of black Christians within white-controlled churches.

The personal artifacts of African-American Christian life on display at the museum are often powerful and poignant. Bibles and printed material dominate, but the connections to individual lives, animate them in unique ways. One can see a hymnal Harriet Tubman used, and Bibles belonging to Nat Turner, Hattie McDaniel, and Second Lieutenant Emily J. T. Perez, a West Point graduate who was killed in Iraq in 2006, as well as the Collins family Bible, purchased in 1869 by Richard Collins of Wilcox County, Alabama, and in which he wrote the record of births in his family, beginning with his own in 1844. A slate notebook belonging to AME Bishop Benjamin Tucker Tanner and a cast iron book stand belonging to AME Zion minister Florence Spearing Randolph in the galleries on Community emphasize the connections among religion, education, and activism. A metalwork cross made by blacksmith Solomon Williams, enslaved on Oakland Plantation in Natchitoches, Louisiana, to mark his wife Laide’s grave and the journal of Rev. Alexander Glennie, rector of All Saints Episcopal Church in Waccamaw, South Carolina open to a page listing marriages of enslaved people points to the importance of religious ritual throughout people’s lives.

Having just published a book about black religious movements that were founded in the context of early twentieth-century urbanization and migration, I was pleased to see this aspect of religious diversity represented in the museum’s exhibits. Visitors can see such items as a hand-made banner from the 1936 Righteous Government political program of Father Divine’s Peace Mission, numerous objects from the Nation of Islam, including a miniature Qu’ran belonging to Elijah Muhammad and a Fruit of Islam uniform and cap, and artifacts from Black Hebrews, such as a prayer shawl and shofar from Rabbi Capers Funnye’s Beth Shalom B’nai Zaken Ethiopian Hebrew Congregation in Chicago. Other aspects of African-American Muslim life in America are also represented in the museum, focusing primarily on the work and legacy of Elijah Muhammad’s son Warith Deen Mohammed. The curators’ work to include people, communities, and events in African-American religious life for whom no objects are available is admirable, and they do so most often through artistic renderings and text panels.

Having just published a book about black religious movements that were founded in the context of early twentieth-century urbanization and migration, I was pleased to see this aspect of religious diversity represented in the museum’s exhibits. Visitors can see such items as a hand-made banner from the 1936 Righteous Government political program of Father Divine’s Peace Mission, numerous objects from the Nation of Islam, including a miniature Qu’ran belonging to Elijah Muhammad and a Fruit of Islam uniform and cap, and artifacts from Black Hebrews, such as a prayer shawl and shofar from Rabbi Capers Funnye’s Beth Shalom B’nai Zaken Ethiopian Hebrew Congregation in Chicago. Other aspects of African-American Muslim life in America are also represented in the museum, focusing primarily on the work and legacy of Elijah Muhammad’s son Warith Deen Mohammed. The curators’ work to include people, communities, and events in African-American religious life for whom no objects are available is admirable, and they do so most often through artistic renderings and text panels.

The museum’s interpretive frame as represented in text panels accompanying objects on display is often less compelling than the powerful artifacts demand. There are numerous panels throughout the museum with headings like “The Church,” “Religion,” “The Black Church,” “The Role of the African-American Church.” In fact, I sometimes had to refer to the visitor’s map to remind myself of the time period and topic of a particular gallery because of the repetition in these unimaginative headings and the fact that they often accompanied similar church pews, stained glass windows, or bibles from a black Protestant congregation. By the third or fourth time seeing such a heading in a museum that is so densely packed with objects, statues, video monitors, and sound, it seems to me that a visitor would be less likely to stop at yet another display case promising a reflection on “the role of the church.” One hopes that the curators incorporate more complex stories in whatever rotating exhibitions they plan in other galleries in the museum and take the opportunity to attend more fully to religious diversity and engage thematic questions that arise from the study of African-American religious history and move beyond the representation of church institutions.

Fortunately, visitors will encounter aspects of African-American religious life in unexpected places throughout the exhibits that give a broader sense of the places and people involved in this history. The story of R. H. Boyd and the National Baptist Publishing Board receives extended attention in a section of the Community galleries on “Making a Way Out of No Way,” and visitors will learn about Boyd’s vision for African Americans to produce their own religious materials and publications. The oratory of black preachers is represented in a section of the Culture galleries devoted to the spoken word and, on the day I visited, a large crowd was gathered around a monitor playing clips of sermons. While both examples I cite have connections to black church institutions, their integration into thematic displays on business and oratory opens up the possibility of interpretive nuance that the repeated headings of “the black church” close down.

The ceremony marking the museum’s opening in September 2016 concluded with President Barack Obama and Michelle Obama helping to ring the bell of Williamsburg, Virginia’s First Baptist Church, formed in 1776 by a group of enslaved and free blacks, that had been removed from its steeple and transported to Washington, D.C. for the event. They were joined by 99-year-old Ruth Odom Bonner, whose father Elijah Odom had been born into slavery in Mississippi and went on to become a doctor and businessman, and three younger generations of her family. Reflecting back on this opening event and the museum’s exhibitions from a post-election vantage point, the presence of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in a place of prominence on the National Mall seems more important than ever. With a president-elect whose rhetoric and platform promote a stereotype of black America as an undifferentiated mass of criminals and crime victims trapped in “the inner cities,” the museum’s depictions of the variety of African-American history and culture, with religion as an important component, is a matter of urgency. With the president-elect’s closest advisors comprised of people who promote racist, xenophobic, Islamophobic, anti-Semitic, homophobic, misogynist, white nationalist views, the museum’s insistence on the interconnectedness of all our American histories, as represented in the motto, “A People’s Journey – Nation’s Story,” stands to face significant challenges, which makes its work all the more important.

Judith Weisenfeld is the Agate Brown and George L. Collord Professor of Religion at Princeton University. She is the author of Hollywood Be Thy Name: African American Religion in American Film, 1929-1949(University of California Press, 2007) and her most recent project is the forthcoming New World A Coming: Black Religion and Racial Identity During the Great Migration (New York University Press, 2016). She can be followed @JLWeisenfeld.