Kelly J. Gannon

“Can you love your neighbor as yourself, and at the same time, knee him in the face as hard as you can?”

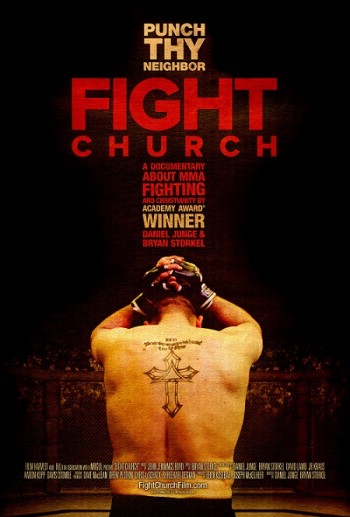

So asks Fight Church, a new film by directors Daniel Junge and Bryan Storkel, that looks at a growing trend in evangelizing ministries that brings mixed martial arts (“MMA”) into the church. The film follows the MMA ministries of several men who are both pastors and fighters. Are fighting and Jesus diametrically opposed? Or is MMA a way to bring “tough guys” to Jesus? These are the main questions that drive Junge and Storkel’s project.

The film begins with Paul Burress, Associate Pastor of Victory Church in Rochester, NY, as he preaches to his congregation: “Because the enemy is out there and he wants to seek and destroy us. He wants to destroy your families. He wants to destroy your person. You need to be prepared in advance.” The movie audience then hears Burress’ story: he grew up wrestling with his preacher father but strayed from the church in his youth, only to recommit his life to Jesus and return to lead his father’s congregation. Burress Sr. notes that allowing his son to create a fighting ministry in the church was an “easy thing to say yes to.” Burgess now leads a muay thai (a combat sport developed in Thailand) and wrestling ministry at Victory Church and lobbies the New York state legislature to legalize MMA fighting. (This legislative debate becomes a large feature of the film.)

Preston Hocker of Freedom Fellowship in Virginia Beach, VA, had similar origins as Burress. Hocker also grew up wrestling with his pastor father and through his school’s wrestling team but he decided to start competing in MMA for a different reason. Hocker describes that around the same time he married his high school sweetheart, a female friend was murdered. Hocker began to worry for his wife’s safety. “I wanted to know that at the very least, I had the ability to defend her life,” he tells the camera. Enter MMA. Hocker, now a semi-professional MMA fighter and associate pastor of his father’s church, trains other men and boys to defend themselves.

This idea of not being pushed around, whether by Satan or a person, is a theme that runs throughout the interviews shown in the film. Although the pastors legitimize their fighting clubs as an evangelizing mechanism (the mantra “Tough guys need Jesus too” is constantly repeated), the programs are also intended to help men defend themselves. “There is nowhere in the Bible where [God] says ‘I want you to be a punching bag for the rest of your life,’” states Burress.

Religious and cultural stereotypes might assume that the majority of these “tough guys” being drawn into evangelical churches are white Southern men. However, the directors note an estimated 700 churches in the United States have MMA ministries; one strength of the movie is how the directors show that this MMA trend is neither racial nor regional. To demonstrate this wide reach, the fighting churches in this film are based in Rochester, Virginia Beach, Clarksville (TN), and Jacksonville (FL). The Rochester church is mostly a white congregation, the Jacksonville congregation is mostly African American, and the Norfolk and Clarksville congregations are fairly racially diverse. Additionally, racially and geographically diverse voices are represented in church leadership and the UFC athletes interviewed for the film.

Other than simply evangelizing to a hard-to-reach demographic, there are other reasons for these ministries as well, including undertones of the Christian Patriarchy movement and Christian militarism. Although neither of these is addressed by name, the film makes clear that husbands are heads of their households and the church. It is their role to speak for, direct, and protect their families.

John Renken, a Tennessee gym owner and former professional MMA fighter who recently started his own MMA-based church, is shown giving his young sons their first guns. “Mainstream or Western Christianity has feminized men [and] taken away their God-given attributes of aggressiveness of competitiveness,” Renken tells the camera. “We expect men to be prim and proper and you’ve got to be polite all the time and you never respond with aggression or with force, almost so they act like females. I think the vast majority of the problems in our society today are because we [men] don’t have a warrior ethos.”

The filmmakers attempt to use Renken’s philosophies to tie the masculinity aspect of MMA fighting to conversations around personal freedom, gun control, and what it takes to raise a boy to be a “real man.” Unfortunately, this is illustrated by shocking imagery of elementary-aged kids with guns rather than presenting the viewer with information about a subculture’s belief system. Renken, for all his faults, is trying to better the lives of his sons and their community by training them to follow in the masculine ideal to which Renken ascribes. This includes teaching his boys to shoot…but only if they stop crying first.

Not all Christian pastors or Ultimate Fighting Championship athletes (“UFC,” the NFL of mixed martial arts) interviewed in the movie believe that Christianity and MMA are natural brethren. Fight Church does a nice job of interweaving conversations with clergymen, athletes, and politicians who believe, as one counter voice says, that fighting “fosters a brutal spirit, not just as a competitor but also as a spectator.” A particularly powerful voice of opposition to MMA churches is former UFC champion Scott Sullivan who, in the course of the film, believes so deeply that fighting is against the “love your neighbor” and “turn the other cheek” teachings, that he leaves the MMA world where he has been a trainer. He opts instead to pursue his PhD in Philosophy (focusing, interestingly enough, on Christian apologetics.)

Directors Junge, whose 2011 film Saving Face won an Academy Award in 2012 for Best Documentary (Short Subject) and Storkel, whose previous major film Holy Rollers also won several accolades, both have experience in filming the cultural impact of religious practices. Despite their familiarity with the religio-cultural realm, however, Fight Church misses some key issues. For example, a New York Times article written by the directors note that fighting ministry pastors “feel that the church’s traditional evangelizing is not resonating with young men anymore.” However, traditional evangelism’s failures are not addressed in the film. Various interviewees mention the need to minister to men in general and “tough guys,” specifically, but the audience is never given a glimpse into alternative methods of evangelism that have failed in the past.

Even more troubling for a film focused on methods of drawing men into the church is the lack of results presented to the audience. How many more men are attending churches now than before these MMA ministries began? How many competitors or even spectators have been “saved” as a result of the ministries? After following its subjects for many years while filming, the movie focuses only on the goals of these ministries rather than bringing up the results.

In the same Times article, the directors also note that they sought to examine “Has the modern church, in the words of one of our subjects, become ‘feminized?’ And does that matter?” It is almost impossible to discuss Christian masculinity without making any comments about Christian femininity. Yet somehow, Junge and Storkel manage to leave women’s voices almost completely out of their film.

Burress’ wife, while not a huge fan of his MMA competitions, is a complacent spectator to his fighting, so long as he can preach on Easter Sunday. We see Preston Hocker’s wife describe how they met in high school but she never comments on her husband’s fighting or that his desire to protect her drove him to MMA in the first place. None of the other wives or women fighters, spectators, or parishioners, have voices in the film.

During a scene about how the church offers fight classes, girls are seen participating in a wrestling class for kids at Burress’ Rochester church. In fact, a twelve-year-old girl tells the camera how much she loves fighting. I was shocked that in an evangelical church, a girl on the edge of puberty would be permitted to wrestle boys. However, the interview is part of a montage of children’s voices; there is no commentary about girls’ involvement in fighting, even in a scene when a young girl wins a wrestling match against a boy. Later, in a church-run MMA competition, a 20-something female member of Burress’ church competes in a bloody amateur cage fight against another woman fighter. Although she loses, Burress publicly praises his parishioner’s resolve during his sermon the next morning. By not giving up, this woman acted like Jesus on the cross, Burress exclaims, “because Jesus never tapped out.”

But how do these women fit into the hyper-masculine world of evangelical, church-run, MMA? I was left wondering about the place of women fighters in the patriarchal theologies that situate men as family heads and defenders. For Biblical literalists, the very nature of a woman fighter seems to diverge from 1 Timothy’s description of womanly modesty and self-restraint. And what would John Renken and his .22 gauge-packing nine-year-old say about Burress’ women cage fighters?

Fight Church isn’t a perfect film, but it is certainly entertaining and raises some interesting questions around modern evangelism and this new form of muscular Christianity. Maybe these issues will be addressed more closely in the directors’ next project… because what’s missing from the one-two punch of mixed martial arts and evangelical churches? That right: a reality television spinoff.

Kelly J. Gannon is a PhD Student in American Religious Cultures at Emory University and Associate Editor at Sacred Matters. She researches religion in the public sphere and historical connections between religion and culture in the American South. She can be followed @K_Gannon.