Hussein Rashid

Introduction: “What does Islam say about images?” It is a question that seeks to understand religion through unitary and static prescriptions. At its core, the question is about what is “Islamic.” Such a question is problematic because a community of believers decides what the religion means. Because human beings are involved, there will be differences. While there are boundaries for who a Muslim is, such as belief in monotheism, the prophethood of Muhammad, and observance of certain ritual and legal obligations, there is a lot more that Muslims believe that is not universally agreed upon, thus generating difference.

The confusion starts because Muhammad played two roles within his community—religious and spiritual authority and polity leader. Like earlier Abrahamic prophets, the combination of the two roles was expected and accepted. As we move away from the time of Muhammad, he takes on different meanings for different Muslim communities and non-Muslim communities engage with Muhammad’s legacy, as well. We have memories of Muhammad that are preserved and represented in a variety of ways.

In the modern period, Muhammad is presented and remembered as the political leader and Islam is seen as a political movement or ideology. This perception is true amongst, both, Muslims and non-Muslims. While this view of Muhammad waxes and wanes, his prophetic character is a more important and more constant aspect of the way he is remembered. For Muslims, Muhammad is the final prophet, who received the revelation of the Qur’an through the Angel Gabriel. By virtue of his prophetic status and by being the first Muslim, he is a figure of veneration and emulation for believing Muslims. He is a gateway through which a believer receives blessings, forgiveness, and proximity to God. The Qur’an says that God and the angels pray for him, that he is granted the power of intercession, and that to make a promise to him to is to make a promise to God. They seek to become better Muslims by learning from and mimicking his actions and words. As a result, for many Muslims, to know about Muhammad is an intrinsic part of faith. This focus on Muhammad generates emotional attachments of love, affection, and devotion for Muhammad and those closest to him.

Muhammad During His Life: Much of what we know of Muhammad’s actions and words are recorded in hadith. Within that, we have records of how people described Muhammad. Collected as shama’il (portraits) literature, we get a sense of how Muhammad looked and the feelings he generated. One of the most well-known descriptions of Muhammad is attributed to his son-in-law and successor, Ali.

He was not too tall, nor was he too short, he was of medium height amongst the nation. His hair was not short and curly, nor was it lank, it would hang down in waves. His face was not overly plump, nor was it fleshy, yet it was somewhat circular. His complexion was rosy white. His eyes were large and black, and his eyelashes were long. He was large-boned and broad shouldered.

And another contemporary of Muhammad, Umm Ma’bad, says,

I saw a man, pure and clean, with a handsome face and a fine figure. He was not marred by a skinny body, nor was he overly small in the head and neck. He was graceful and elegant, with intensely black eyes and thick eyelashes. There was a huskiness in his voice, and his neck was long. His beard was thick, and his eyebrows were finely arched and joined together. When silent, he was grave and dignified, and when he spoke, glory rose up and overcame him. He was from afar the most beautiful of men and the most glorious, and close up he was the sweetest and the loveliest. He was sweet of speech and articulate, but not petty or trifling.

Veneration of Muhammad continued to evolve in ritual and artistic life. Poetry, a popular form of spirituality across Muslim cultures, is replete with devotional works to Muhammad, praising his qualities and seeking proximity to him. The poetic tradition lends itself to song and even Bollywood movies incorporate these devotionals into their repertoires. In addition to poem and song, which are still written, composed, and performed in the modern period, a strong tradition of painting Muhammad emerges.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Go71P2UPgkc https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kf044eaWcck https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TSIkgRLdWYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AUsZFHH2pPs

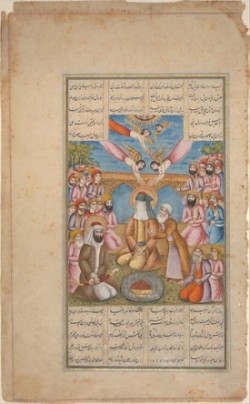

Muhammad in Painting The paintings of Muhammad depict his entire life, from his birth, to his call to prophecy, and beyond. Along with Muhammad, we see other figures who are important to the spiritual lives of Muslims, including figures like Salman al-Farsi and Muhammad’s closest family.

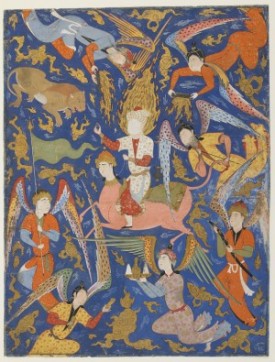

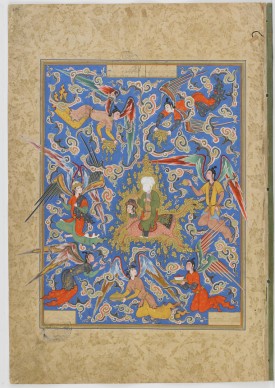

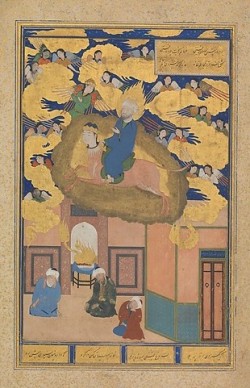

One of the events of Muhammad’s life that lends itself to illustration is his ascent to heaven to speak with God. Known as the mir’aj, he is carried by Buraq and winged horse with the head of a woman. The imagery itself demands to be painted. Beyond that, the mir’aj is an important spiritual lesson. It demonstrates that God is approachable and immanent.

For Muslims, that Muhammad has a special relationship with God is a critical part of the faith. He is not just a source of law, or a political leader, operating under specific historical circumstances. To limit him in this way is to miss the idea that religion is not simply instrumentalist and political. If religion is the way a community structures itself to express faith, and faith is the individual attempt to reach some sort of transcendent reality, then we have to see the paragons of a religion as metaphysical figures, as well. Muslims do not use imagery during their formal worship services. Mosques are decorated with geometric patterns, Arabesques, and calligraphy. The strong and clear prohibition against idol worship in the Qur’an results in a natural cautiousness in presenting Muhammad, or other spiritual leaders. At the same time, Muhammad is blessed, and is a conduit of blessings (barakah). His description, images of him, his relics, and his family are all reminders of that aspect of his prophecy. This sort of respect and veneration is an integral part of the tradition, and the reasoning relies on the Qur’an and hadith. It is because of the openness of both corpuses to interpretation that we see such variety in the ways Muhammad is represented. There are no easy ways to determine if a community is comfortable with figural representations, there are some generalities we can observe. Shi’ah communities create images for devotional expression and remembrance. However, some of the most well-known depictions of Muhammad come from Sunni Turkey. Sufism, a type of Islamic esotericism, is made up of a variety of orders, and each has their own limits on the creation of images. Even within these patterns, there are nuances. There are communities that will only represent him in words, those that will mask his face, and those who have no objections to the representation of Muhammad. In an ideal world, these parameters would be defined by theological reasoning. However, history has shown us that it is also conditioned by political realities. There are periods in time where beautiful representations of Muhammad are destroyed as a sign of political control.

Muhammad in the Modern Period: The Saudis do this today by demolishing any space related to Muhammad. For them, it is a tool to narrow the meaning of Muhammad, so that it is not the prophetic voice that animates the religion but the Saudi state. As a result, there is a popular conception that Muhammad can never be represented, despite evidence to the contrary dating back to his companions.

This erasure of cultural memory feeds into a fearful conception of faith, which is brittle and can be easily broken. While there are those with sincere beliefs around not representing Muhammad, what this modern prohibition does is turn Muhammad into an idol. The focus on not focusing on him, of making sure he is not seen, elevates him to divine status, as it is only God who cannot be represented. The Wahhabi movement, and the nihilist movements they spawn, are the most forceful voices against any appreciation of Muhammad.

Just as there are forces that seek to destroy the memories of Muhammad in the present day, there are also traditions that continue the task of recognizing him as a source of blessing. Sufi Comics is a modern approach to the miniature tradition that seeks to impart moral learning, ethical reasoning, and devotional thinking while representing Muhammad and his family. Michael Muhammad Knight wrote a well-known poem “Muhammad was a Punk Rocker,” to pull out the revolutionary nature of the prophetic revelation that sought to uplift the dispossessed. There is a long tradition of non-Muslims depicting Muhammad, and many of the earliest representations, such as Dante’s, were quite negative. At the same time, figures such as Gandhi and Washington Irving, attempt to see Muhammad as Muslims do. In the Supreme Court of the United States, there is a representation of Muhammad in a frieze as a lawgiver. Islam is not a living thing that we can say “Islam says…” Islam does not speak, Muslims do. At the same time, Islamic tradition is aniconic in worship, but it is not iconoclastic. While Muslims do not use images in worship, they do live in a visual world and engage that sense in worship. Therefore, Muslims turn to Muhammad as an ideal to which they aspire and seek a variety of ways in which they can be inspired by him. He is not just statesman, but prophet.

Hussein Rashid holds a PhD from Harvard’s Near Eastern Languages and Cultures. He is currently a faculty member at Hofstra University and Associate Editor at Religion Dispatches. He also serves on the Advisory Board for Sacred Matters Magazine.

SOURCES Ernst, Carl W. Following Muhammad: Rethinking Islam in the Contemporary World. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003. Safi, Omid. Memories of Muhammad: Why the Prophet Matters. New York: HarperCollins, 2009.