Scott Muir

In a recent Sacred Matters post, Gary Laderman suggested that the recent widespread celebration of the Grateful Dead represents both a plentiful harvest of the seeds sown in the countercultural upheaval of the 1960s and a harbinger of the future of religious life in a country increasingly disaffiliated from major religious traditions. Earlier this month, I surveyed 147 Deadheads anxiously awaiting the band’s penultimate concert to explore the influence of the band on everyday Deadheads’ religious identities.

First of all, my sample clearly indicates that Deadheads are indeed estranged from traditional religion. When asked, “Which religious tradition do you currently identify with, if any?” more than half reported that they have none or are agnostic, while less than a third identified with a major religious tradition. 62% of respondents reject the religious tradition they were raised in, though most of these describe themselves as “indifferent” rather than “opposed,” and self-described atheists are nearly as rare as in the general population. Still, the “Terrapin Nation” which bassist Phil Lesh asked God to bless during the band’s final encore is clearly much less conventionally religious than the American public—even when we take into account the fact that it is disproportionately white, male and middle-class. Within “the Scene,” “organized religion” is regularly denigrated as passé, overly restrictive, and at odds with primary shared values such as authenticity and self-determination.

On the other hand, results suggest that Deadheads are not secularists. Rather, they prefer the more individualistic and unbounded language of “spirituality” to describe their engagement with the sacred. While a majority report that “religion” is “not at all” or “not too important” in their lives, over three quarters assert that “spirituality” is “very important” or “somewhat important.” Many commentators have critiqued the concept of “spirituality” as vapid to the point of meaninglessness, but it does seem to provide a window into the operation of the sacred in the “secular” yet thoroughly enchanted world of the Grateful Dead. Preliminary comparisons of response rates to questions included on a nationally representative Pew study revealed that my respondents are about twice as likely to report faith in “spiritual energy in physical things,” astrology, reincarnation, and yoga as a spiritual practice as the general population. Deadheads also appear considerably more likely to report mystical experiences, contact with the deceased and ghosts and consultations with psychics and shamans. As a group, Deadheads seem disproportionately high on the core psychological trait of “openness to experience” and elevate it to the status of a primary virtue. Consequently, while they generally eschew adherence to the strictures of a particular religious tradition, they are exceptionally open to experiences of the sacred, particularly those perceived by others as “out there.”

For many Deadheads, it doesn’t get much more sacred than a show. An overwhelming 80% report that there has been a “spiritual quality” to their experiences at shows and nearly half of these say “frequently.” Moreover, 86% affirm that there is a “shared spiritual culture, connection or energy permeating this scene.” Deadheads describe both the personal and collective experience of a show in terms highly resonant with Durkheim’s famous concept of the “collective effervescence” at the heart of religion. Respondents repeatedly report feeling “connected” through the shared experience of music—to the present moment, the inner self, friends, fellow concertgoers, the band, humanity, the universe, even God. The nature of that connection is variously described as “transcendent,” “mystical,” “energetic,” “enlightening,” and “magical,” grounded in “reverence,” “freedom,” “love,” “wholeness,” “synchronicity,” “universal consciousness,” or simply shared values and tastes. Regardless of the metaphor or mechanism, Deadheads frequently assert “we are all one,” or as one respondent put it “there is a clear connection to everyone on an almost cellular level.” Many affirm that “we are all here for the same reason,” though a definitive articulation of that reason remains elusive. Many frankly acknowledge the role that drugs, especially psychedelics, play in facilitating such experiences but argue that they are mere tools and not constitutive of the experience. Some even draw favorable functional comparisons to religion, describing a Dead show as “my church,” a place where one can experience “the joy of indeterminate ritual—communion without shared dogmatic beliefs.

Deadheads also widely endorse the notion that these musical experiences of the sacred have shaped them religiously. Nearly three quarters affirm that the culture surrounding the band and their performances have influenced their “religious/spiritual identity,” but responses are generally a bit more hesitant and qualified here for the same reason that “organized religion” is suspect. Within this individualistic counterculture, ascribing influence to any large-scale cultural phenomena seems to threaten a thoroughgoing commitment to radical subjectivity, which ascribes complete spiritual authority to the individual. Thus, Deadheads are comfortable describing their experiences with the band as formative to the extent that those experiences are understood to be a collective, participatory phenomena that further enhances their openness and individuality, rather than a top-down performance engendering conformity. Some explicitly credit the Dead with helping them to “think beyond [their] ‘traditional’ religious practices” and “open [their] mind while holding my own beliefs” through “expanded consciousness” and the experience of “love and freedom [without] proselytization.” Others attribute ethical and spiritual benefits such as benevolence, hope, gratitude, or even “seeing others as they truly are,” while some simply shrug and observe, “it’s who I am.”

It is the alternative character and quality of the social world that gradually gathered around the Grateful Dead that has granted it its significant cultural power as much or more than the wealth of music the band created over the course of its “long strange trip.” And that social world is more of a continual, collective reimagining of the counterculture of the ‘60s than it is a true continuation of it—an ongoing “psychedelic tradition” if you will. Fare Thee Well felt more like a multi-generational extended family reunion than a big baby boomer stroll down memory lane. The fairly low average age of my cross-sectional sample (34) is indicative of the steady stream of fresh converts throughout the band’s half-century history. It is important to remember that the Grateful Dead were largely a minor, local phenomenon when psychedelic rock was popular enough to have a real countercultural edge—that is, when it was perceived as both significantly large and threatening to pose a significant critique to mainstream culture.

The Dead built their subcultural empire through a grassroots marketing strategy during the heyday of disco and over-produced pop in a manner that passively bypassed rather than proactively countered popular culture. The exponential growth of this subculture facilitated by the Dead’s expansion from dancehalls in the 1970s to football stadiums in the 1980s continued apace through the 1990s and into the 2000s as a wide variety of “jam bands,” and Grateful Dead side projects and spinoffs rose up to carry forward the Dead’s mantle in the wake of Jerry Garcia’s death.

Like most American subcultures, “the Scene” possesses a powerful influence on adherents’ identities, values, consumption patterns and politics to the degree that it presents a more or less coherent alternative to mainstream culture. That alternative is in turn generally ignored by the wider society, except of course, for the occasional parody.

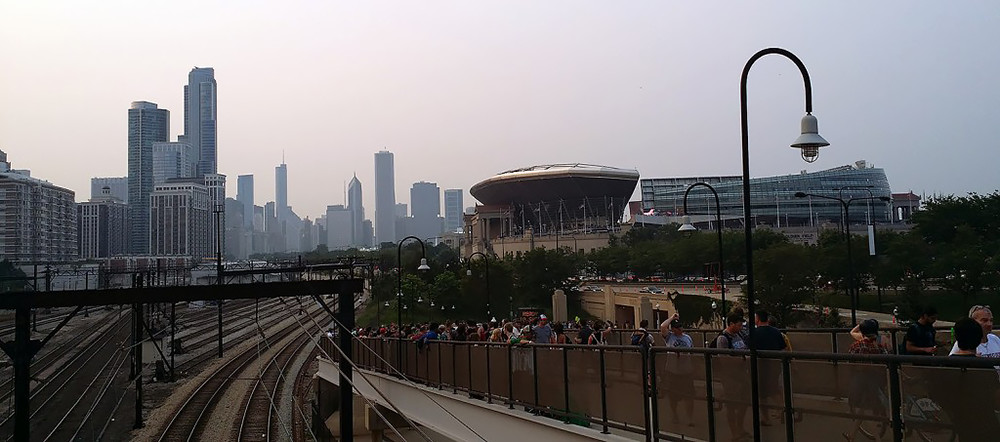

The widespread, glowing coverage of the Dead’s 50th anniversary celebration through mainstream media outlets (not to mention a nod from the White House) signals yet another shift. The originally radically countercultural and later decidedly subcultural “psychedelic tradition” has been gradually transformed from an isolated subculture to yet another offering on the mainstream American cultural menu. Fare Thee Well was more than a handful of big concerts; it was a major national phenomenon. All five shows were streamed live to countless bars, movie theatres and living rooms across the country using the most powerful video and audio technology available. The city of Chicago was overwhelmed by many thousands more Deadheads than could fit in Soldier Field on any given night, and the excess spilled into dozens of other cover band and jam band shows held throughout the long weekend at venues around the city. Even the skies were filled with planes and blimps bearing classic Dead lyrics. I experienced firsthand how these shows and the massive response fostered far more than a few football stadiums worth of collective effervescence—from the multi-generational streaming party I attended at a former stranger’s home in Raleigh on Friday night, to the day-long trek my wife and I made from Durham to Soldier Field on Saturday, to the Sunday “Weir World” stream party in Chicago for those unable to score tickets for the final show to the Jerry tribute after-show held at the House of Blues in the wee hours of Monday morning. I have entered the alternative reality surrounding the Grateful Dead and their ilk countless times, but I have never seen that world take over the “real world” like this before.

Scott Muir is an instructor in the department of Philosophy and Religion at Western Carolina University and doctoral candidate studying American Religion at Duke University who writes on religion and live music, and religion in higher education. This article is posted in conjunction with his blog, The Spirit of the Scene, which presents ongoing analysis of research regarding religious identities and spiritual culture in the American live music scene.