Jason Bruner & Ryan Linde

Christianity is the most persecuted religion in the world.

This is a bold—and, perhaps to some, counterintuitive—statement, made most substantively by the renowned Catholic journalist John Allen Jr. in his recent book, The Global War on Christians. But Allen is by no means alone in making the claim. From the halls of the U.S. Congress to European human rights organizations, Christians are described as a group under attack. Given the truly horrific stories (warning: graphic content) that occasionally accompany such claims, it is hard to deny that certain Christians around the globe are facing severe repression.

But is there really such a thing as a global war on Christians? Where does the claim come from?

I. Persecution and the Early Church

The claim grows out of the theological soil of the early Church. In the Gospels, Jesus warned that his disciples would need to “take up their cross” in order to follow him (cf. Matt. 16:24, Lk. 9:23), a statement that foreshadowed the early Christian connection between experiences of persecution and the expansion of the Christian movement (Acts 11:19). True disciples should expect suffering, physical, and otherwise.

Early Church Fathers tell us that many heeded the call and Christianity’s first centuries are often still associated with the gruesome, heroic, and spectacular accounts of those who suffered at the hands of a Roman Empire inherently opposed to Christian belief. But those same Church Fathers sought to show that imprisonment, torture, and even death could not tamp down the Christian movement. Tertullian’s famous quip highlights the irony: “The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church.”

By the time Eusebius, Christianity’s premier early historian, put pen to parchment, there were hundreds of martyrologies floating around the Mediterranean. Eusebius incorporated these heroic accounts of faithful perseverance in the face of death into a master narrative that chronicled the unlikely, but providentially inevitable, spread of a persecuted faith amidst hostile imperial forces.

Eusebius worked to separate true Christianity from what he believed were aberrations and heresy by compiling dramatic snapshot accounts of Christian martyrs from across the Roman world. In some cases, like with the Montanists, he believed that martyrdoms could distinguish the true Church from those who were doctrinally suspect. Cowardly Montanist heretics hung themselves like Judas, while the orthodox stood firm in the face of Rome’s attempts to combat Christian belief (Eccl. Hist., Book 5, ch. 16).

Persecution was evidence that one was on God’s side in a cosmic contest. The persecuted, therefore, were righteous, innocent victims who held firm to the faith that the Romans had tried to eradicate. Eusebius’s histories provide a stark comparison between the privilege Christians experienced under Constantine with the purported repression they had endured prior to the Edict of Milan (313 CE). Constantine providentially rose to power to protect persecuted and beleaguered Christians.

To early Church Fathers, persecution had one source (the devil) and Christians were persecuted for one reason (their faith). In the words of Eusebius, martyrs were “the trophies won from demons, the victories over invisible enemies” (Eccl. History, Book 5, para. 3-4). Talking about martyrs, therefore, drew a line in the sand and for this reason, martyrdoms are not often marked by their geopolitical complexity. Martyrdoms made clear the apocalyptic dichotomy. As Candida Moss explains in her recent book, The Myth of Persecution:

Readers come away with the impression that the heretics and the demons are in league with one another. The orthodox Christians, the church, are just like the martyrs. The heretics that Eusebius is denouncing are just like the demons that attack the Christians. Even from the beginning, then, Eusebius starts weaving the themes of his history together, so that he can group different sets of opponents into a single class. In this situation martyrs now stand for the church. They become a kind of litmus test for orthodoxy and truth (p. 221).

While the claim of Christianity’s uniquely persecuted status is based upon contemporary events, those who espouse it are heirs to ancient Christian vocabulary, theological frameworks, and narrative structures.

II. Counting Martyrs

In recent years, numerous sources have proffered that there are presently about one hundred and five thousand Christian martyrs every year —a figure that might even stun Tertullian. How can one account for this sobering statistic?

The figure was calculated for the World Christian Database at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, which has been tracking global religious demographics for decades. The numbers of “martyrdoms,” however, are estimated from an aggregate total over a decade, which is divided by ten to get an annual average for that decade.

As others (including Allen) have noted, to get the dramatically high number of one hundred and five thousand martyrdoms (or similarly high numbers from the 1990s), one needs to include deaths from a wide variety of conflicts. Not only have high tallies of the “global war on Christians” occasionally included all victims from the Rwandan genocide, but other calculations, including the World Christian Database, have also included a significant percentage of victims from the subsequent wars in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Because both of these conflicts have contributed to the shockingly high numbers of victims of the global war on Christians, they deserve a closer look.

The conflicts in the DRC have claimed as many as five million lives, many of whom are Christian. For the sake of tracking global martyrs, however, the World Christian Database counts 20 percent of deaths in the DRC as “martyrs.”

So, who is waging the “war on Christians” in Rwanda and the DRC? It’s mostly other Christians.

According to the Pew Research Center, just over 95 percent of the DRC identifies as Christian, with only 1.5 percent identifying as Muslim. Similarly, the overwhelming majority of Rwandans (approximately 90 percent) identified as Christian (the majority of those, Catholic) at the time of the 1994 genocide.

However, using numbers from either the Rwandan genocide or the wars in the DRC as statistical evidence of a global war on Christians risks glossing over the fact that many (if not the majority) of the perpetrators of both conflicts were themselves Christian and that neither conflict can be understood primarily as a battle against Christians or Christianity as such.

To suggest that these atrocities are best understood as part of a global war on Christians, therefore, neglects how these conflicts are embedded in complex international conflicts in addition to how ethnicity, resource allocation, regional politics, and other factors have contributed to the development and perpetration of severe violence in the region. Also, especially in the case of Rwanda, it neglects Christian churches’ complicity in the development of the politicization of ethnic identity in the twentieth century.

In both countries, of course, there have been examples of people whose Christian faith has led them to put their lives at risk for the sake of others or to take a moral stand in the face of atrocity and death. It is undeniable that the violence has been horrific, but the question here is whether it is accurate and appropriate to cite the dramatically high figures derived from these conflicts as evidence that there is a global war on Christians costing over one hundred thousand lives per year.

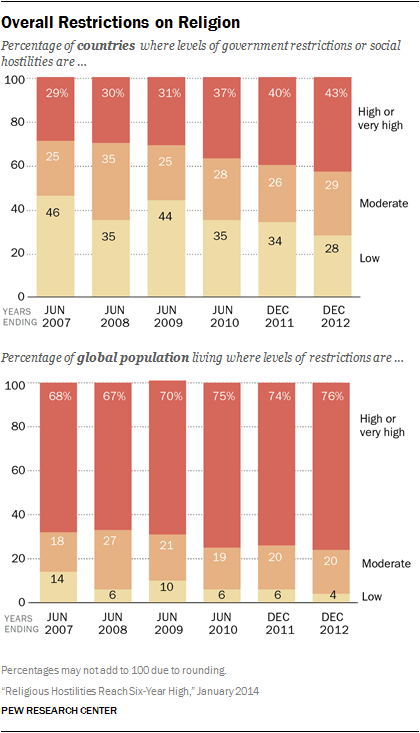

There are, however, other metrics besides the annual number of “martyrs.” Take, for example, the Pew Research Center’s recent report on increased restrictions of religious freedom that tracked a slight increase in restrictions on religion around the globe as of 2012. They concluded that Christians were most affected by these restrictions. This conclusion is akin to earlier findings from Martin Lessenthin of the International Council on Human Rights who stated in 2009 that 80 percent of religious discrimination in the world occurs against Christians.

But do these statistics really evince a war on Christians or Christianity?

III. What Does It Mean to Say That Christianity Is the Most Persecuted Religion in the World?

In the past eighteen months in particular, Christian news sites have frequently featured headlines such as the following: “‘Deny Christ or Die,’ Boko Haram Tells Young Christian Woman.” The narrative of these stories is that Boko Haram is primarily and fundamentally an anti-Christian movement whose purpose and goal is to eradicate Christians and Christianity, and Christians, who are persecuted solely because of their faith, are wholly innocent.

This narrative neglects the fact that Goodluck Jonathan (a Christian) acceded to the Nigerian presidency through deeply controversial means and that for years before the formation of Boko Haram, there were Christian militias organizing in Nigeria’s middle states. According to NigeriaWatch.org, the clear majority of attacks have not been against religious targets but rather against police outposts, government buildings, businesses, and public areas like bus stations. Significantly, this narrative overlooks that there are a significant (though unknown) number of Muslim victims of Boko Haram.

Gérard L. F. Chouin somewhat problematically estimates that there may be as many as three times more Muslim victims of Boko Haram’s violence as there are Christian victims, because so many of the attacks have been in public locations in which the population is heavily Muslim. His analysis, however, does not appear to factor in rates of conversions in these areas since the 1980s, which Darren Kew considers to be an important factor in the development of the violence.

Nevertheless, Christian news outlets purvey the narrative of righteous Christian innocence and a fundamentally anti-Christian movement in Nigeria. None of this is to say that Christians in central and eastern Nigeria are not experiencing violence; it is simply to suggest that how that this violence is presented and understood through early Christian categories and theology. In other words, Eusebius is still using martyrdom to draw lines in the sand.

The style and content of those who advocate for the “persecuted Church” owe much to the literary style of a long line of Christian martyrologists. One could mistake large swathes of Allen’s The Global War on Christians for Eusebius’s Ecclesiastical History or John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. All offer a series of decontextualized snapshots of individuals or small groups who faced opposition, oppression, or death.

Very much unlike Eusebius or Foxe, however, contemporary advocates of the global war on Christians tend, by the necessity of their argument, to cast a wide net in describing who counts as a “Christian” and what counts as a “war.” Those who describe a global war on Christians implicitly adopt a very generous, non-dogmatic definition of “Christianity” to cull evidence in support of their narrative.

While this is, in part, an “ecumenism of blood,” as Pope Francis termed it, it also, by virtue of an experience of “persecution,” defines as “Christian” those who otherwise might not be regarded as such in a different context. That is, to sustain a narrative of a global war on Christians, it becomes necessary for evangelical Christians to recognize the Christianity of Orthodox or Roman Catholics. And vice versa.

Allen even includes non-Trinitarian Christians in Iran to bolster his claim of the global war on Christians (much to Eusebius’s chagrin, one imagines). But this newfound ecumenism has its limits. One is hard-pressed to find anecdotes from Allen (or on relevant advocacy sites like Open Doors USA or Voice of the Martyrs) pertaining to Latter-Day Saints, Seven-Day Adventists, or Jehovah’s Witnesses, for example. Eusebius still has his theological biases.

This theological move of broadly defining “Christian” begins to place strands of the Christian tradition simultaneously in the role of global persecutor and persecuted, as Orthodox Christians oppose Pentecostals in Russia while they also face violence in Syria. Or Coptic Christians, who have been the focus of much Western attention, are also cast as the “enemy” when they oppose Pentecostals. Or as Roman Catholics in Nigeria have their churches bombed but then become hostile towards evangelicals in southern Mexico. To justify the inclusion of Christian violence on other Christians as evidence of a global war on Christians, Allen simply states: “Sometimes the war on Christians is a civil war.”

The global war on Christians, therefore, is sometimes expressed as communists vs. Christians, Muslims vs. Christians, atheists vs. Christians, “animists” vs. Christians, and even Christians vs. Christians. None of these anti-Christian opponents seems particularly aware of their common enemy. “Global war” rhetoric, therefore, conflates a variety of social, cultural, political, religious, and economic contexts, subsuming them under a common bellicose rubric. One wonders at this point how helpful the rhetoric of “war” is in understanding and resolving these conflicts.

To go back to the war’s body count: If one removes the DRC atrocities from the tally of contemporary Christian martyrs, the number drops precipitously from over one hundred thousand to below ten thousand. In fact, Thomas Schirrmacher of the World Evangelical Alliance, someone who is not at all interested in minimizing perceptions of Christian persecution, has estimated the number of martyrs to be between seven thousand and eight thousand. So, the global war on Christians has between seven thousand and one hundred and ten thousand victims per year, depending upon one’s definition of “martyr.” Allen’s goal, however, is not really to track martyrdoms; it is to convince the reader that Christianity can be—and is—persecuted at all.

Following Eusebius, speaking of martyrs tends to frame conflicts involving Christians as based fundamentally in their Christian belief and/or identity and that Christians are wholly and inherently innocent. In part, having recourse to the rhetoric of “global war” reinforces ancient theological notions peculiar to Christianity: you will be persecuted and your persecution will be a sign that you are righteous.

There is no question that some Christians are experiencing severe hardship and violence, as are many others around the globe. “Global war” rhetoric, however, hides the violence done against others, as it assumes that Christians are always the primary intended target of adverse government policies or violence. For example, a US Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) report states that in Indonesia certain blasphemy laws primarily target Ahmadiyya, not Christians, as is also the case in Pakistan. And in Iran, there are perhaps several times as many Baha’is imprisoned as Christians. Speaking of a common global to persecute Christians frames this violence as being primarily and fundamentally anti-Christian in origin and intent.

Eusebius did not write to capture geopolitical complexity. Neither is it why his contemporary heirs write about the persecuted Church. Nevertheless, Christianity’s global demographics have changed dramatically in recent decades, so that roughly two-thirds of all Christians now live in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Pacific Islands. Becoming not only the largest—but also the most geographically dispersed—faith has meant that Christianity often exists as a faith of minorities. This reality illuminates the nature of Christian conversion (who converted, when, and why), in which the new faith was often appropriated within contentious political and ethnic conflicts. Such historical variables problematize an exclusive evaluation of many conflicts as being inherently religious or anti-Christian in nature.

While examining particular cases of regional violence and oppression often reveals more complex variables and narratives than simply anti-Christian sentiment, the rhetoric of a “global war on Christians” is evidence of a tendency to map the world into homogenized identities. Here, the burgeoning younger churches of the global South have become the idealized early persecuted Christians of the first Christian centuries. As such, they are often seemingly regarded as righteous and opposed by forces that are only and inherently demonic.

If we have some reason to be skeptical of Eusebius’s presentation of the early Christian martyrs, associated as they were with highlighting Constantine’s imperial privileging of Christianity, then we might also have similar reason to be skeptical of his modern-day progenitors. For the blood of today’s martyrs may be the seed of American imperialism.

Jason Bruner is assistant professor of Global Christianity at Arizona State University. He is a scholar of religious history with a particular interest in the history of Christian missions and the growth of Christianity in Africa and Asia in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. He can be followed @jason_bruner.

Ryan Linde is a recent graduate of Arizona State University with a BA in Religious Studies. He plans on pursuing graduate studies in Early Christianity and New Testament studies.