In our interview series, “Seven Questions,” we ask some very smart people about what inspires them and how their latest work enhances our understanding of the sacred in cultural life. For this segment, we solicited responses from Prema Kurien, author of Ethnic Church Meets Megachurch: Indian American Christianity in Motion (NYU Press, 2017) .

What sparked the idea for writing this book?

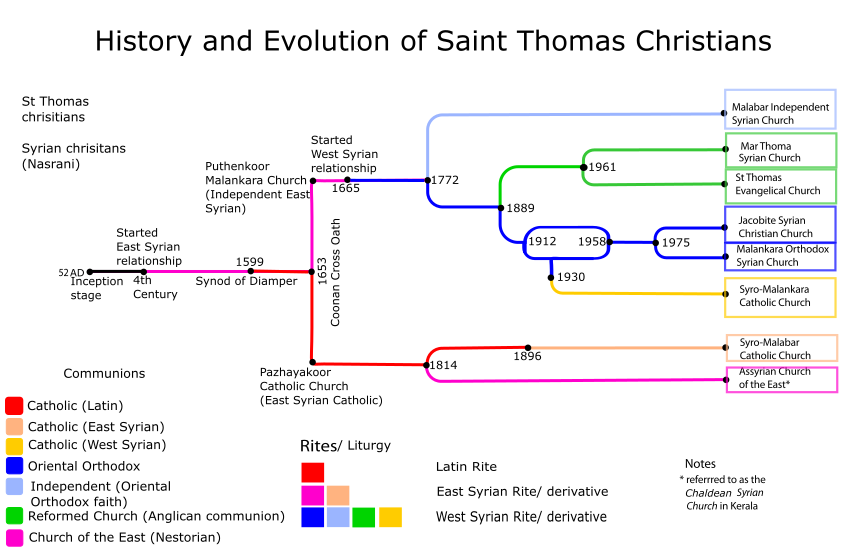

I undertook this research as part of a larger project focusing on the political mobilization patterns of the four major Indian immigrant religious groups in the United States – Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, and Christians – around homeland issues. I had done some work on Hindus and Muslims and started my research on Indian Christians with the Mar Thoma church (part of the Syrian Christian tradition in Kerala that developed out of the contact with the Middle East in the early centuries of the Christian era) since some of its members and achens (pastors) had taken the lead in mobilizing the Indian Christian community in the United States to protest attacks against missionaries and Indian Christians taking place in several parts of India. I found very quickly that although Mar Thoma members were from Kerala state in India, known for its highly mobilized and politicized citizenry, most of the congregation was indifferent toward Indian national political developments. However, because of the close ties between the Mar Thoma home church based in Kerala and the U.S.-based diocese, church members were immersed in denominational politics. The mobilization of Indian-American Christians in different parts of the United States around attacks against Christians in India soon petered out and was subsequently led by a national umbrella organization, Federation of Indian American Christian Organizations of North America, FIACONA.

I undertook this research as part of a larger project focusing on the political mobilization patterns of the four major Indian immigrant religious groups in the United States – Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, and Christians – around homeland issues. I had done some work on Hindus and Muslims and started my research on Indian Christians with the Mar Thoma church (part of the Syrian Christian tradition in Kerala that developed out of the contact with the Middle East in the early centuries of the Christian era) since some of its members and achens (pastors) had taken the lead in mobilizing the Indian Christian community in the United States to protest attacks against missionaries and Indian Christians taking place in several parts of India. I found very quickly that although Mar Thoma members were from Kerala state in India, known for its highly mobilized and politicized citizenry, most of the congregation was indifferent toward Indian national political developments. However, because of the close ties between the Mar Thoma home church based in Kerala and the U.S.-based diocese, church members were immersed in denominational politics. The mobilization of Indian-American Christians in different parts of the United States around attacks against Christians in India soon petered out and was subsequently led by a national umbrella organization, Federation of Indian American Christian Organizations of North America, FIACONA.

Nonetheless, I continued with the research on the Mar Thoma church – the focus of this book – because I found it to be an excellent case study of the problems faced by ethnic churches in the United States. My prior research on Hindus of Indian background in the United States examined how the process of being transformed from a majority in India to a minority in the United States affected Hindu Indian Americans, and the ways in which various Hindu American organizations—religious, cultural, and political—attempted to address questions about minority status and identity outside their homeland. What interested me about the Indian Christian case was that it exemplified the reverse process from Indian Hindus, since Indian Christian immigrants move from being a small religious minority in India to becoming part of the majority religious group in the United States. My research showed that immigrant churches like the Mar Thoma face several challenges if they are to successfully institutionalize as an “ethnic” church in a context where Christianity is the majority religion. An important issue is how to retain the allegiance of the second and later generations to an “ethnic” Christianity in the face of the intense competition from American evangelical churches.

In facing this challenge, it became clear that the transnational nature of the Mar Thoma denomination was its greatest asset, but also its biggest liability. The Eastern Reformed Mar Thoma denomination based in Kerala, south India, is part of the ancient Saint Thomas Syrian Christian church that traces its origin to the legendary arrival of Apostle Thomas on the shores of Kerala in 52 CE. Although the denomination has parishes around India and the world, its administration is centralized in Kerala, South India, and maintains control over the global network of Mar Thoma parishes. The administration rotates achens around its parishes on three-year terms. A consequence of this centralization is a remarkable uniformity among the ritual and organizational practices of Mar Thoma parishes in different countries, all of which maintain its ancient St. James liturgy (translated into Malayalam). In other words, the denomination is able to maintain its distinctiveness and identity as a unique church in the American context through its connections to Kerala and its Malayali-speaking achens. At the same time, the second-generation often felt that achens from India did not have the English-language skills and the knowledge of the American context to preach sermons that were relevant to their lives. They also felt that the short terms of the achens were a barrier to their getting to learn about the needs of the church and the American-born members. Consequently, many second generation members were leaving the church, which raised questions about the long-term prospects of the Mar Thoma church in the United States.

How would you define religion in relation to your work? Where do you see the sacred or sacred things in this book?

This is my most conventional sociology of religion book since it is a study of a Christian church and congregation. However, what was striking to me were the differences in the way the two generations understood the meaning of being Christian. Those who immigrated to the United States from Kerala generally interpreted being Christian as the outcome of being born and raised in a Christian family, sacralized by infant baptism into the church community. They also saw their religious and ethnic identity as intertwined – for them, heritage, faith, and denomination were bound together and were all conferred by birth, as was the case of most other social groups in India. The older generation told me that they had been taught about Christianity by their families and the Mar Thoma community: their parents, grandparents, other members of their extended family, and the local church. For the immigrant generation, being a good Christian (in India and the United States) meant attending the local Mar Thoma church every Sunday and participating in its activities, reading the Bible and praying every day, and being a “moral” person.

Second-generation Mar Thoma Americans, on the other hand, had imbibed several of the ideas of American evangelicalism and tended to view a Christian identity as the outcome of achieving a personal relationship with Christ, often beginning with a “born-again” experience. Although second-generation American Mar Thomites grew up in the church and attended the services regularly in their childhood and teenage years, they had a very different understanding of the relationship between ethnicity and religion from the immigrant generation. Like many other religiously oriented second-generation Asian Americans almost all of the second-generation members who were regular church goers––whether they currently attended the Mar Thoma church or a nonethnic church––separated their religious identity from their ethnic or sectarian identity, and said that their Christian identity was primary.

This decoupling of religion and ethnicity was partly a consequence of how they had learned about Christianity. Unlike East Asian American youth, for whom family remains the most important influence on religiosity, all the young people I talked to who said that religion played an important role in their lives indicated that their primary sources of information about Christianity were not their parents or the achen, or even the Sunday school, as had been the case for their parents. Many had attended private Christian schools and so had first learned about Christianity through the classes and speakers at the school. School and college friends and campus Christian groups were an even more important source of knowledge and of support. A few had done a lot of reading on their own. They also mentioned television programs and web sites. Most of the older cohorts of Mar Thoma second-generation members indicated that when they left home for college they “became Christian” through their involvement in evangelical churches and groups.

The differences in the meaning of being Christian also meant that immigrants and their children had very different conceptions about the church, its mission, and structure, as well as the role of the pastor, the type of sermons they wanted to hear, the language that should be used for worship services, the importance of liturgy, and even the type of worship songs sung in church.

Can you summarize the three key points you’d like the reader to walk away with when finished?

There is a lot of literature on how nondenominational evangelicalism and the rise of American megachurches are “remaking” American mainline churches and American religious traditions. But American evangelicalism has also had a profound impact on the churches of recent immigrants, resulting in pressures to incorporate evangelical worship styles, often at the expense of maintaining their ethnic character and support systems. This is the first point that I would like the reader to understand.

Second-generation (and some first-generation) American Mar Thomites participated in a variety of evangelical institutions including campus groups, Bible study fellowships, and an array of evangelical churches. Television, internet, and radio ministries, Internet websites, and books provide other sources of influence. In interviews and conversations, however, the type of church that came up most frequently and to which the Mar Thoma church was compared, was the large transdenominational or nondenominational churches – the U.S. megachurches. Megachurches offer several services over the weekend, and sometimes even during the week, with slick multimedia presentations and contemporary music led by professional bands. They also have programming for a variety of age groups.

Describing the attraction of such churches, Vilja, a 1.5 generation (those born abroad who immigrated as young children) woman in her forties, explained that the youth in her Mar Thoma congregation liked “the short contemporary service, the music, pastors who are fluent in English, and sermons that are well put-together, and have life application.” Shoba, another young woman, a second-generation Mar Thoma American who had left the Mar Thoma church, was enthusiastic about the large nondenominational church she attended along with her husband. “They have an amazing band, and amazing musicians. And we just love worshiping there. It brings a lot of people from the community in because it’s like a free concert on Sunday morning – bagels and doughnuts too!”

Shobha’s description of the service at the megachurch that she attended as a “free concert on Sunday” is very apt. In these churches, the carefully choreographed, emotionally-charged productions with dramatic mood lighting, video enhancement, and professional music are designed to create an uplifting atmosphere. This is probably why many of the Mar Thoma youth described such churches as being “on fire for Christ.” They contrasted this type of worship experience with the sedate, formal service and the off-key congregational singing in Mar Thoma churches. Evangelical megachurches are also structured very differently from the Mar Thoma church. While the Mar Thoma churches are small and community-oriented, megachurches are large and impersonal – but many of the second generation I interviewed thought that the lack of community orientation of these evangelical churches actually helped to foster spirituality. Although the older, immigrant generation said that it was important for them to know “the person who is sitting next to me in the pew,” the younger generation considered the social aspect of the Mar Thoma church a hindrance to being able to focus on God during the service.

The services at megachurches are also much shorter than at the Mar Thoma church, which means that people could fit in many other activities during the day. If they went to a Mar Thoma church on the other hand, most of Sunday was spent on the commute, the service, and church activities. The financial obligations for Mar Thomites attending megachurches were also lower than at a Mar Thoma church. Due to these considerations, in the United States, small, ethnic churches like the Mar Thoma face competition for their youth from the large megachurches that have become a ubiquitous part of the contemporary American Christian landscape.

In the Mar Thoma case, the widespread prevalence and dominance of American evangelicalism created an environment in which the traditional practices of the Mar Thoma church seemed alien to its American-born generation. Second-generation Mar Thoma Americans were influenced by nondenominational American evangelicalism and often rejected the “ethnic,” denominational worship practices of the Mar Thoma. They argued that being a “closed” ethnic church was “not Christian.” But their attempts to introduce non-liturgical praise and worship services in English, open to individuals of all backgrounds, were resisted by members of the immigrant generation for whom the church functioned as an extended family and social community. Consequently, many second-generation Mar Thomites left the Mar Thoma church for large nondenominational churches once they reached adulthood. Others attended both Mar Thoma and evangelical church services. Yet others stayed in the Mar Thoma church, but worked to transform church practices to be closer to the evangelical church model.

The second point I would like the readers to understand is that American evangelicalism is also transforming the religious context in India. The rise of charismatic, evangelical, or Pentecostal churches is a global phenomenon. They can also be seen all over India. Although there are a large number and variety of such churches, locally called “New Generation Churches” in Kerala, some of the first were initiated by return migrants. Many of the new churches in Kerala and around the country are also believed to be thriving due to the contributions coming in from evangelicals in the West, particularly the United States. Consequently, international migrants and foreign connections have played an important role in initiating and sustaining these churches. People are drawn to the new generation churches because of the “intense spiritual experiences” they provide through the rousing singing, dancing, and occasionally the faith healing that takes place during services, the charismatic, practically oriented sermons of the preachers, and the personal attention the church is able to dispense to members who confront problems. Many traditional, episcopal denominations like the Mar Thoma find themselves without the resources to counter the global spread of nondenominational evangelicalism. Since these churches are based on very different socio-cultural ideas about personhood, autonomy, and spirituality, many might find themselves eventually losing their rich history and traditions.

Finally, and this is the third point, this book makes clear why a global approach is important to our understanding of the movement of religions and people around the world. The biggest limitation of migration studies frameworks is that they currently focus primarily on the one-directional influence of either the home or host society instead of examining the impact of both home and host societies on migrants, as well as the impact of migration on home and host societies. Similarly, frameworks of religious change are currently focused on national processes. Since most religious organizations in the contemporary period operate within global fields and are affected by international migration it is important to ensure that our frameworks also take transnational and global dynamics into account to gain a better understanding of the multifaceted process of religious transformation taking place around the world.

Ethnic Church Meets Megachurch investigates how transnational processes shape religion in both the place of destination and the place of origin. Taking a long view, it examines how the forces of globalization, from the period of colonialism to contemporary large-scale out-migration, have brought about tremendous changes in Christian communities in the global South. Until the sixteenth century, Syrian Christians were integrated within Hindu Kerala society as a high-caste warrior group below only the Brahmins in status. They participated in Hindu religious ceremonies and upheld Hindu pollution and purity rituals and rules while maintaining a distinct religious identity from the Hindus, Muslims, and Jews in Kerala society. Syrian Christians in Kerala resisted Portuguese attempts at Latinization for decades, arguing that they were bound by the “Law of Saint Thomas” and not the “Law of Saint Peter.” But they were eventually incorporated into Roman Catholicism through a combination of deception and force. The British Anglican missionaries who followed the Portuguese were less confrontational. Nonetheless, they tried to purge Syrian Christians of both Roman Catholic and Hindu influences in their attempt to restore the church to its “ancient purity.” The British were able to gain some converts to their Anglican church, and influence others like the Mar Thoma to reform their theology. More recently, the international migration of Mar Thomites to the Middle East and the West has had profound impacts on the home church.

Who were intellectual models or inspirations for you as you wrote this book?

I stumbled into religion and its role in shaping migration through my dissertation research but I did not consider myself a sociologist of religion. A postdoctoral fellowship from the New Ethnic and Immigrant Congregations Project (NEICP), directed by R. Stephen Warner and Judith Wittner, which included a summer training workshop in 1994, introduced me to the sociology of religion, specifically the literature on religion and migration. One of the first books I read that summer was The Madonna of 115th Street: Faith and Community in Italian Harlem, 1880-1950 by Robert Orsi, a beautifully written book which made a tremendous impression on me. The work of other NEICP scholars on immigrant religion, R.S. Warner’s book, New Wine in Old Wineskins: Evangelicals and Liberals in a Small-Town Church on the impact of evangelicalism on a small-town Presbyterian church, as well as Stephen Ellingson’s The Megachurch and the Mainline: Remaking Religious Tradition in the Twenty-First Century examining how Lutheran churches in the San Francisco Bay area were “remaking” their Lutheran traditions in response to the popularity of evangelicalism were also important influences. Finally, the work of sociologists of immigration such as Peggy Levitt, and Robert C. Smith looking at the transnational relationships and connections of immigrants played a major role in shaping my ideas. I read Roger Waldinger’s The Cross-Border Connection: Immigrants, Emigrants, and their Homelands as I was finishing my book manuscript, and that was very impactful as well.

What was the most difficult thing about writing the book? Did you encounter any unexpected problems or challenges?

Because of the secularity of sociology, religion is a relatively marginal field of study within the discipline, and within the sociology of immigration (my primary field of expertise). As I have mentioned, this book is the most clearly focused on the sociology of religion among my three books. It also deals with a relatively overlooked group, Christian immigrants from India. For both of these reasons, I decided that it had to be a post-promotion book. But by then I had got involved in administrative work of different types and other research projects and it was difficult to carve out the time to get it written!

What’s the most unexpected response, critical or positive, that you’ve gotten about the book?

Very soon after the book was published, I received an email from a person who said he was a second-generation member of a Syrian Christian church denomination related to the one that I focus on in the book. The young man told me that he had read my book to understand the history of his own church and its future in North America (the early history of both denominations is the same and many of the central dynamics in the United States are similar). He said he had really enjoyed the book and that it has been particularly helpful in “illustrating the challenges to passing down a more communal understanding of faith to the future generations.” I was surprised that someone had finished reading the book so soon since it had just become available to the public. The young man replied saying that he had finished reading it quickly since he found that he “couldn’t put it down.” This is the biggest compliment I have received about any of my books!

With this book done, what’s up next for you?

I am currently working on a book manuscript, Race, Religion, and Citizenship: Indian American Political Advocacy that uses a case study of Indian Americans to understand the factors that spark the political mobilization of new immigrant and ethnic groups and the strategies they use to achieve political power. What I find particularly striking about Indian Americans is that they have mobilized around a variety of identities to influence U.S. policy. Some identify as Indian Americans, others as South Asians, and yet others on the basis of religious identity as Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, and Christians. A growing group identifies in terms of their party affiliation as Democrats and Republicans. There is also an adult, second-generation population that is getting involved in civic and political activism in very different ways than from their parents’ generation. My research focused on a variety of Indian American advocacy organizations and discovered that differing understandings of race, as well as majority/minority status in India and in the United States produced much of the variation in the patterns of civic and political activism of the various groups.

I am also working on a National Science Foundation-funded research project, “The Political Incorporation of Religious Minorities in Canada and the United States” examining how the social, political, and religious contexts of Canada and the United States impact the patterns of political incorporation and mobilization of religious minorities from South Asia. This research studies how different opportunity structures (both national and regional), and differences in the characteristics of the groups shape how they frame their grievances and mobilize.

Prema Kurien is Professor and Chair of Sociology as well as the founding director of the Asian/Asian American Studies program at Syracuse University. She is the author of two award-winning books, Kaleidoscopic Ethnicity: International Migration and the Reconstruction of Community Identities in India (Rutgers University Press 2002), and A Place at the Multicultural Table: The Development of an American Hinduism (Rutgers University Press 2007). This piece is based on her third book, Ethnic Church Meets Mega Church: Indian American Christianity in Motion (New York University Press 2017). She is currently working on her next book, Race, Religion, and Citizenship: Indian American Political Advocacy, and on a research project, “The Political Incorporation of Religious Minorities in Canada and the United States.”