Joseph P. Laycock

God’s greetings, all within the house!

I’m friend to all, St. Nicholas.

Have no fear, just look at me.

No wild stranger here you see.

My coming marks the year’s near end.

This Forest Man my basket tends.

Deeds good and bad we must review.

With ringing bells comes Krampus too,

What brings him joy brings terror to you.

While American parents might bring their children to a mall to meet Santa Claus, this poem, written by Patrick Deisl of Gastein, Austria, and translated by Al Ridendour, describes a very different kind of Christmas encounter. In Gastrin, children traditionally look forward to a hausbesuch (house visit) from St. Nicholas and his entourage, usually on December 5 (the Eve of Nicholas’ Feast Day). While the American mall Santa might be accompanied by his wife or some cheerful elves, in Austria St. Nicholas’s companions may include a strange forest hermit bearing a basket of goodies and a friendly angel. But almost invariably St. Nicholas is escorted by Krampus, a demon complete with horns, goat legs, and a lolling tongue. During the hausbesuch, while St. Nicholas thumbs through his book to determine whether the children have been good, Krampus (or more often a small troupe of Krampuses) lurk in the shadows, whips at the ready to punish naughty children. Krampus costumes typically include chains and oversized cowbells so that children can hear the hausbesuch party’s approach. Even when Nicholas pronounces the children good and gives them their candy, the Krampuses often run amok in the house, enraged that they have been deprived of their sadistic pleasures. The Krampuses make a scene and may even turn their whips on the parents (though rarely the children) before St. Nicholas calls them to heel and the troupe moves on to the next house.

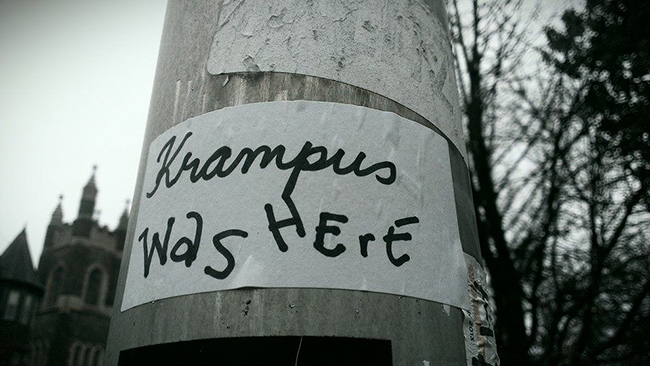

Krampus is now becoming as familiar to Americans as our red-and-white-suited Santa. Last year two horror films, Krampus and A Christmas Horror Story featured the character. The Austrian tradition of Krampuslauf (Krampus runs) has also spread to America. In more urban areas the Krampus troupes of the hausbesuch evolved into public parades of menacing Krampuses. Krampus runs have now been held in two-dozen American cities. Last year’s Krampus run in Bloomington, Indiana, drew an estimated 31,000 spectators. Exactly why this obscure Alpine Christmas demon has suddenly exploded into global culture remains unclear.

Krampus’s origins are murky. Al Ridenour’s excellent The Krampus and the Old, Dark Christmas (2016) is both a reflection of contemporary Krampus-mania and the definitive English book on the subject. Krampus’s ancestry begins in Western Austria and surrounding regions, where villages separated by mountainous geography allowed numerous variations on the Krampus tradition to develop. As is often the case with folkloric entities, Krampus is known by many names, some of which elide into related but distinct entities. Krampus bears some similarities to other Germanic “dark servants” of St. Nicholas such as Zwarte Piet in Holland and Knecht Ruprecht in Germany, the later of which also punishes children. Ridenour concludes that Krampus has existed “in one form or another” since the eighteenth century.

“Krampus” seems to have emerged as the dominant term for the Austrian entity in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth-centuries. This is partly due to the effect of mass media on vernacular culture. After the founding of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1867, a new mail system made it possible to send postcards. By the late 1880s, people were exchanging “Krampuskarten” (Krampus Cards) on St. Nicholas Day. These cards were often inscribed with the words “Gruss vom Krampus” (Greetings from Krampus) and featured frightening images of Krampus abducting children. In one Krampuskarten the Krampus capers in front of a fire where an assortment of hearts roast on a spit. The hearts bear weeping faces, suggesting the souls of naughty children. Another shows St. Nicholas sternly rebuking Krampus, who crouches at his feet bearing a pitchfork.

“Krampus” seems to have emerged as the dominant term for the Austrian entity in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth-centuries. This is partly due to the effect of mass media on vernacular culture. After the founding of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1867, a new mail system made it possible to send postcards. By the late 1880s, people were exchanging “Krampuskarten” (Krampus Cards) on St. Nicholas Day. These cards were often inscribed with the words “Gruss vom Krampus” (Greetings from Krampus) and featured frightening images of Krampus abducting children. In one Krampuskarten the Krampus capers in front of a fire where an assortment of hearts roast on a spit. The hearts bear weeping faces, suggesting the souls of naughty children. Another shows St. Nicholas sternly rebuking Krampus, who crouches at his feet bearing a pitchfork.

The Krampuskarten spread the Krampus legend beyond Austria. They also likely had a homogenizing effect on the Krampus’s name and appearance, much as Coca-Cola ads lent cultural dominance to the image of Santa in a red and white suit. The Krampuskarten images appear to draw inspiration from devils featured in Christian morality plays as well as the Greek god Pan.

In the 1930s (the same decade that artist Haddon Sunblom began painting Santa for Coca-Cola), there was a revitalization of Krampus traditions in Austria. Craftsmen began constructing more sophisticated Krampus masks (larven). Krampus culture continued to grow throughout the 1940s and 1950s but was still had little following beyond rural towns of Austria and Bavaria.

A reference to Krampus appears in Harper’s Magazine as early as 1873. But Krampus was mostly unknown in America until 2003 when Chicago author and art curator Monte Beauchamp published The Devil in Design: The Krampus Postcards, a book of lavish color reprints of vintage Krampuskarten. Suddenly, scanned images of Krampus were all over the Internet. (Beauchamp followed through with several other Krampus projects, including a sticker book.) Before long, people in the United States, the UK, and even Japan were creating their own Krampus costumes. At the same time, there was a revival of Krampus culture in Austria with larger Krampus runs and increasingly elaborate costumes.

As often happens when cultural traditions cross oceans, Americans altered Krampus and some of these changes may have even been exported back to Austria. Ridenour reports that Austrian designers now have heated debates concerning whether proper Krampus costumes should feature such elements as latex musculature and red LED lights in the eyes or if these innovations are “too American.”

American films have steered the Krampus toward the role of Santa’s rival (the Anti-Claus) rather than his unruly servant. A Christmas Horror Story features an elaborate fight scene between Krampus and Santa in which Santa calls Krampus the “vile enemy of Christmas.” This antagonistic role seems somewhat indebted to Dr. Seuss’s character The Grinch as well as the 1964 stop-motion classic “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” in which Bumble the Abominable Snowman nearly eats Rudolph’s parents.

The American Krampus’s transition from St. Nicholas’s enforcer to his rival also mirrors the evolution of Satan: In the Book of Job, Satan is “the adversary” of humanity but remains loyal to God, but by the time of the Gospels, Satan has become the enemy God as well as His creation. The re-imagined Satan helped to explain why a benevolent God would allow evil to exist. Perhaps Americans are uncomfortable with the idea of a Santa that would work alongside Krampus.

So why are Americans so enamored of Krampus? And why now? A common theory is that Christmas has become too saccharine and materialistic. For some, Christmas can be a dark, depressing time and Krampus provides the vocabulary to confront our own darkness. Krampus’ malevolence can even restore meaning to the holiday by raising the stakes. Michael Dougherty’s film Krampus emphasizes that the spirit of the holiday is not giving, but sacrifice. This film assures audiences that they are not monsters for resenting their obnoxious family members who visit for the holidays; and yet if we cannot muster some hospitality for these unwanted guests, real monsters will come.

The Krampus also appeals to people interested in the secret lore of Christmas. An article on the Krampus written in 1958 by folklorist Maurice Bruce declared that Krampus is actually “the horned God of the witches” and even suggested that his whip is a phallus and his chains a survival of Pagan initiation rituals of death and rebirth. Bruce’s interpretation of Krampus is likely indebted to Margaret Murray’s 1931 book “The God of the Witches,” which argued that the Christian devil is actually “the Horned God” of an ancient European witch-cult. Murray believed that remnants of the witch-cult might have survived into the modern era. For folklorists like Bruce, Krampus serves as a reminder that the modern Christmas floats on the surface of the deep sea of Pagan solstice traditions.

There is one more key to Krampus’s appeal: the experience of terror may not be far removed from the experience of the sacred. Theologian Rudolf Otto in The Idea of the Holy suggested that the sacred comes from a sense of awe at “the wholly other,” which primitive humans may have first experienced as a sense of “daemonic dread.” Otto’s phenomenological approach is certainly not without its critics among religion scholars. But it is worth considering how an element of fear and the monstrous changes the holiday experience. When Christians complain that American culture has “taken the Christ out of Christmas,” this is partly a lament that an event meant to inspire religious awe now merely inspires commerce. Krampus may not have the power to make Christmas sacred, but by bringing terror he at least staves off banality.

Imagine an American child standing in line at a crowded mall for a chance to sit in Santa’s lap while Christmas music drones on the speakers and frustrated parents check their text messages. Now imagine a child in an Austrian farmhouse on St. Nicholas Eve listening for the bells that signal the approach of masked Krampuses in the darkness. For one of these children, meeting St. Nicholas still represents an encounter with “the wholly other.”