By Beth Singler

“Captain Planet, he’s our hero,

Gonna take pollution down to zero,

He’s our powers magnified,

And he’s fighting on the planet’s side.”

Travel back with me now through the mists of time to when dinosaurs roamed the earth and a much younger version of me returned each day from school to settle down on the couch with a choccy biscuit and that afternoon’s cartoons. On very special days these lyrics—written by no less a musical luminary than Phil Collins himself—would blast out of my television to let me know that I was in for thirty minutes of planet saving, eco-conscious adventure.

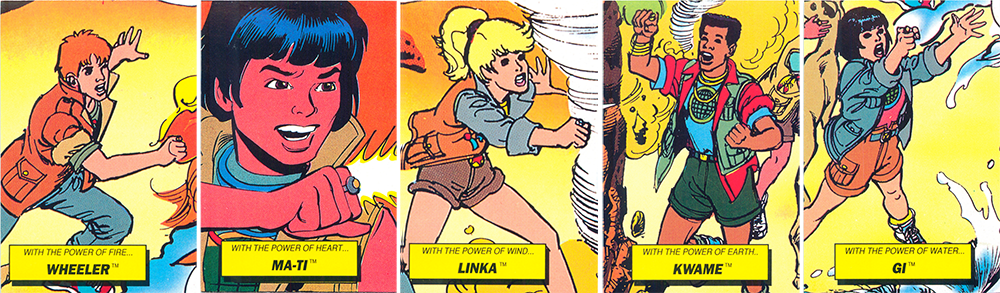

Captain Planet and the Planeteers was the second longest running cartoon of the 90s with 113 episodes produced by Turner Program Services. In the first of these, “A Hero for Earth,” Gaia, the spirit of the Earth—who probably owes a lot to James Lovelock but her voice to Whoopi Goldberg—brings together five teenagers from the five corners of the earth and gives them magical rings that can summon the elements. Serious Kwame from Africa controls the element of Earth. Wheeler, a loud-mouthed New Yorker, controls Fire. Linka, a logical Russian who often rebuffs Wheeler’s romantic attentions, controls Air. Gi, a wannabe marine biologist from Asia controls Water. And finally, Ma-Ti from the Brazilian rainforests controls that less well-known element, Heart, which gives him the ability to talk to animals and to imbue compassion into people through telepathy.

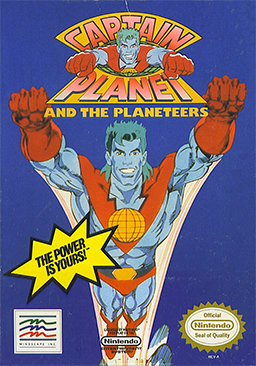

Using their magical rings and ingenuity, these plucky teenagers took on terrible corporations and toxic monsters such as Hoggish Greedly, Verminous Skumm, Dr. Blight, and Looten Plunder. But even they got into trouble they couldn’t handle sometimes (well, in every single episode, in fact). And when that happened, the five combined the powers of their rings to summon Captain Planet himself, like a genie from a bottle. This blue-skinned, green-haired superhero would then save the day, beating the baddies, at least until next time. But he always told his entranced audience of children out there in the real world that “The Power is Yours!” We could all be Planeteers and do our bit to save the world.

Why am I taking you on this rather colourful trip back down memory lane? My PhD research is on the Indigo Children, an idea from within what is broadly known as the New Age Movement. You may not have come across this term before. In the late 1970s, a woman named Nancy Ann Tappe, who described herself as having both synesthesia (in her case, seeing colours around objects and tasting shapes) and the “sight” (psychic gifts), claimed to have started seeing children with indigo auras. She had previously seen auras of colours relating to the lower chakras, such as red, orange etc., but these new children, she thought, were coming at a particular point in history and were being born with their own life missions. The different colours corresponded with three different parts of the human whole: the physical, mental, and spiritual dimensions, echoing the tripartite view of man as body, mind, and spirit that is often found in modern metaphysical religion. Other authors such as Jan Tober and Lee Carroll (psychics and channellers) claimed that, in their work as self-help lecturers, counsellors, and authors, they had begun to notice “emerging patterns of human behaviour,” particularly in children, and that they had identified a new “kind of problem for the parent” (Carroll and Tober, 1999: xi–xii). They assumed that these changes and the attributes of these new children would be noticed by mainstream mental health professionals and researchers, but the lack of response convinced them to write The Indigo Children—The New Kids Have Arrived as a “beginning report” on the situation (Carroll and Tober, 1999: xv).

Now the Indigo Children are described as special. They have a sense of their life mission but also a feeling of entitlement, and often they have difficulties fitting into the society that they are here to change. These children may be diagnosed by the unawakened medical profession as having ADHD, autism, or other medical problems that the professionals see as warranting medicating. There has been some media attention for the Indigo Children, in particular around 2006 when Jenny McCarthy announced that she had been identified by a strange woman as an Indigo child and her autistic son as a Crystal Child (a newer form of Indigo). She recounts that she had instinctively replied with an emphatic “yes!” By 2007, she had stopped mentioning Indigos and started blaming her son’s vaccinations for his autism instead. Prominent news channels such as CNN have also covered the Indigo Child idea.

What is key is how Indigo Children, like the Planeteers, are considered to be on Earth for a reason; they have a life mission to save the world. They are described as being more spiritually evolved with “magical” or psychic abilities, such as telepathy or telekinesis, and a greater awareness of the connected life force or energies of the universe. In my work, I am considering some of the antecedents for the Indigo Children concept, tracing it (as others have done with the New Age Movement as a whole) through previous ideas and forms seen in Spiritualism, Theosophy, and even in Christianity with the veneration of particularly holy children who have been given visions and prophecies for the world.

I had already begun to think about the transmission of these ideas through popular media when an interviewee from my research mentioned Captain Planet and the Planeteers. He said, “The Indigo Children grew up on shows, cartoons, films, etc. with lots of symbolism and metaphysics behind them.” He also mentioned FernGully: The Last Rainforest, an animated film with a strong environmental message and the Mighty Morphin Power Rangers, an Asian import involving yet more teenagers being chosen to save the world from often toxic monsters. My interviewee claimed that these kinds of messages were intentionally included for audiences that included Indigo Children.

This idea of television shows as disseminators of secret or esoteric knowledge is not uncommon. For example, there were two main conspiracy theories around Chris Carter’s extremely popular TV show The X-Files, which first aired in 1993. Briefly, the X-Files were the unsolved, mystery, or down-right odd cases that the FBI dumped into storage that were then taken up by the UFO believer, Fox Mulder. His skeptical partner, Dana Scully, joined him to investigate and, in time, they uncovered witches, vampires, mutants, and most importantly, aliens, and a government cover-up and plot. The two conspiracy interpretations of Carter’s influential series were, first, that this was an attempt to slowly leak out “The Truth” through the media and get the population ready for the reveal about the genuine existence of aliens on earth. Or second, that this was a cynical ploy by “Those in Command” to turn interest in UFOs into the preserve of the weird and the geeky who would then be dismissed. Aliens as entertainment could then distract us to The Truth, whatever it might really be.

In the case of programs like Captain Planet and the Planeteers, it is hard to provide proof of an undercover agenda for the dissemination of New Age ideas and attitudes beyond the environmentalism that the New Age has long had an affinity with. We can, however, describe some of the interests and sympathies of those involved in the production of the programme. For example, Ted Turner, whose Turner Program Services created and broadcast Captain Planet on his channel, Turner Broadcasting Services (TBS), has expressed environmentalist sentiments and has connections with well known New Age entrepreneurs such as Maurice Strong, founder of the holistic community in Crestone, Colorado. Strong introduced Turner at the “World Millennium Peace Summit” in 2000, a summit that was part funded by Turner and TBS. In his Peace Summit speech, Turner said, “We are all one race, and there is only one God that manifests himself in different ways,” a sentiment that received a standing ovation, according to Lee Penn in his anti-religious universalism book, False Dawn: The United Religions Initiative, Globalism and the Quest for a One-World Religion (2005).

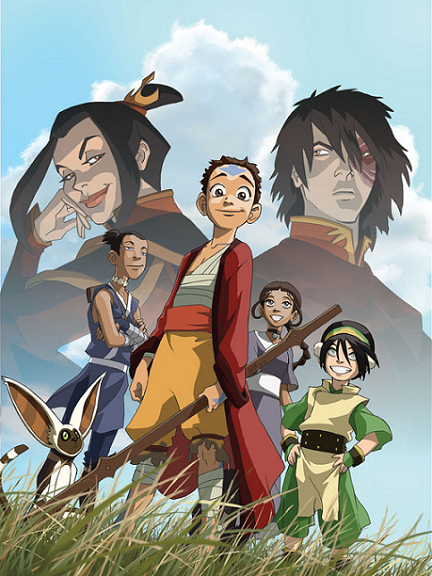

We can also certainly point to the marked increase in interest in these ideas and in new spiritualities in recent decades. Likewise, we can see the obvious increase in the number of programs with spiritual or supernatural storylines such as Buffy The Vampire Slayer, Angel, The Dresden Files, Charmed, Tru Calling, The Ghost Whisperer, Supernatural, True Blood, Lost Girl, Sleepy Hollow, and the list goes on. A list of TV programs and films that repeat the Indigo Child/psychic/savant/super-powered kids trope could include The Tomorrow People (in the 70s, 90s, and now in 2014), Heroes (and soon, Heroes Reborn), Fringe, Touch, Mercury Rising, Knowing, and Avatar: The Last Airbender.

In fact, the last example, that of Avatar: The Last Airbender, is particularly pertinent. Not only does it also include plucky young manipulators of the elements, but we can actually trace the flow of ideas to and from the Indigo Children in this example. In a piece Jon Ronson wrote about Indigos in August 2006, he refers to a story in the Dallas Observer that involved an interview with an Indigo Child of eight years old:

“Earlier this year, the Dallas Observer ran an article about Indigo children.

One eight-year-old was asked if he was Indigo. The boy replied: “I’m an avatar. I can recognise the four elements of earth, wind, water and fire.”

The journalist was impressed.

After the article ran, several readers wrote in to inform the newspaper of the Nickelodeon show Avatar: the Last Airbender. In the cartoon, Avatar has the power to bend earth, wind, water and fire. The Dallas Observer later admitted it felt embarrassed about the mistake.”

This then, is one of the main interests of my research: seeing the connections between the spiritual and the media and how they mutually influence each other. In the case of Captain Planet and the Planeteers, the idea that “The Power is Yours” is particularly resonant with the Indigo Children, who are thought to be now in their 30s and possibly making television programs and after-school cartoons of their own. And, don’t tell anyone, but I might still be watching, biscuit in hand, after long day at “school” working on my doctorate.

Beth Singler is a PhD student at the University of Cambridge specializing in the social anthropological study of new religious movements online. Combining traditional fieldwork with digital ethnography, she explores the new definitions of self that multiply on the Internet. Her PhD research is on the Indigo Children, and she has also written about Wiccans, Jedi, Scientologists, pop-culture religions, and various online subcultures. You can follow her on Twitter via @BVLSingler.