S. Brent Plate

*Warning: the following article reveals spoilers about the Mad Men series finale.

In episode 9 of the final season of Mad Men, Don Draper sits in his empty Manhattan penthouse, having lost his wife and all his domestic possessions. A few episodes later he is driving his Cadillac through the western states with nothing but a bag of belongings. In the ultimate scene of the penultimate episode he gives his car to a local grifter.

These final episodes turn Don into a Dharma Bum, some modern-day bodhisattva eliminating attachments through carefree wandering. He’s straight out of Japhy Ryder’s vision in Jack Kerouac’s 1958 novel Dharma Bums, in which Ryder sees “millions of young Americans wandering around refusing to subscribe to the general demand that they consume production and therefore have to work for the privilege of consuming all that crap they didn’t really want anyway, such as refrigerators, TV sets, cars, at least fancy new cars, certain hair oils and deodorants, etc.” And maybe Don becomes that, and maybe he always was detached. But that’s not all.

The irony is that Don’s job as an ad man was to get people to do the opposite: to purchase things, to spend money on services and products they may or may not need, to acquire, to buy and buy in. Without attachments, barely even to his name or family, Don’s work revolved around getting other people attached to things.

Don Draper is an unaffiliated priest in the religion of consumerism.

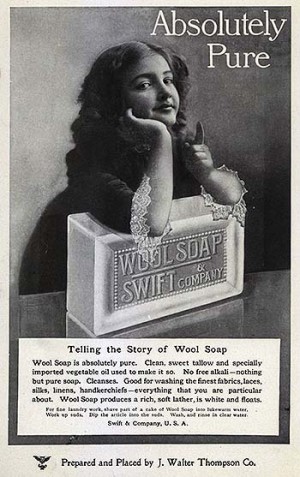

Part of Mad Men’s brilliance has been to show the trajectory of advertising mythologies from the 1950s to the 1970s. During this time advertisements, and the men and women who made them, shifted from the old fashioned extolling of a product’s intrinsic qualities (big, clean, quick) to the creation of a longed-for lifestyle surrounding the product (the counter-cultural symbol of denim jeans, the world singing in perfect harmony, being like Mike). Products were no longer sold, dreamed-of lives were. Myths, rituals, and symbols bolstered this strange new religion.

Don was successful because he listened to and observed people, and then he learned how to tell stories with them, for them, and to them. In other words, he was a mythmaker par excellence. He saw need and desire, and converted them into real world applications: tell a story, set a scene, create an alternate world. In turn, people will listen, follow, and consume in ritualistic fashion.

But in this religion—arguably the dominant religion in the United States for the past half-century—the authentic and the inauthentic get swapped. In the very first episode of the series Don tells department store maven Rachel Menken, “What you call love was invented by guys like me, to sell nylons.” Don gets it; he’s selling dreams. He’s never had any illusions about the fact that it is all an illusion. Even the old ads, trying to directly sell a product for their intrinsic value, were fake.

Rachel’s death in the final season touches Don, one of the rare cuts through his cynicism. There was something authentic in her life, and then death, that is a counter to Don’s life; Rachel’s sister tells Don that she “lived the life she wanted to live.” Yet he remains unaffiliated, polymorphously and perversely so.

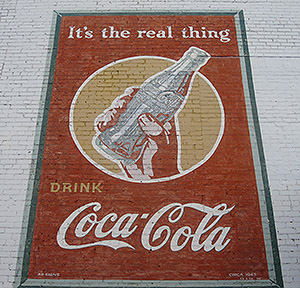

Here’s the inspired thing about the final minutes of Mad Men. A fictional show, imaginatively mirroring a 1960s reality, fades out to a real television advertisement. And not just any advertisement, it’s the holy grail of advertising: Coca-Cola and their iconic 1971 “Hilltop” commercial. (I’ve been using this ad in my religious studies classes for years.)

Writing in Variety Brian Steinberg says, “In tying the series protagonist to a verifiable touchstone of real U.S. popular culture, creator Matthew Weiner may have worked to link his entire oeuvre to the world which in the past it has only mirrored.” Steinberg is on to something here, this collapsing of the real and the imagined, art and life and all that. The commercial actually existed, and it existed just after the time Mad Men’s fictional world ended. The jarring revelation of that final minute of melodic sweetness was the inbreaking of something real, right there in the midst of us devotedly watching Don’s inauthentic life.

And yet, there is another layer in which the logic is off. The “real” commercial includes singers wanting to give the world a Coke because it is “the real thing.” The real thing—Weiner laughs all the way to the bank—is a bottle of sticky-sweet, bubbly brown water.

What Matthew Weiner has done is demonstrate the fictional reality of the real world itself. There is no layering of inauthenticity surrounding the authentic heart. It’s turtles all the way down. Don was his vehicle, his priest.

Don the Draper, the concealer, covers up the windows of the real. He’s not the man behind the curtain. He’s the curtain itself. And we gaze so devoutly at these drapes, no longer caring that we can no longer see out the window, or whether there was ever anything to see in the first place.

S. Brent Plate is a visiting associate professor of Religious Studies at Hamilton College. His most recent book is A History of Religion in 5 1/2 Objects: Bringing the Spiritual to Its Senses. He is also co-founder and managing editor of the journal Material Religion: The Journal of Objects, Art, and Belief and a contributor to The Huffington Post and Religious Dispatches. He can be followed @splate1.