Amy Kittelstrom

The following is an excerpt from The Religion of Democracy: Seven Liberals and the American Moral Tradition by Amy Kittelstrom, published on April 21, 2015 by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © Amy Kittelstrom, 2015.

Introduction: An American Reformation

Somehow the word “godless” got hitched to the word “liberal.” The story of this coupling has something to do with the Cold War against communism, but behind this unholy union lies a much more interesting history of how some American elites led a very different fight against—well, elitism. Seven liberals, whose lives interconnected across two centuries through shared readings, relationships, and concerns, were so far from godlessness that the pursuit of truth and virtue dominated their lives. The history they lived shows that after the Protestant Reformation in Europe came an American Reformation that built a moral tradition into democracy.

John Adams, the irascible, prideful second president of the United States, did not consider all people fit to vote, yet he thought every man had the right to make up his own mind about what to believe about politics, religion, or anything else—not only the right, but the duty to think for himself, because the only being who really knows everything is God.

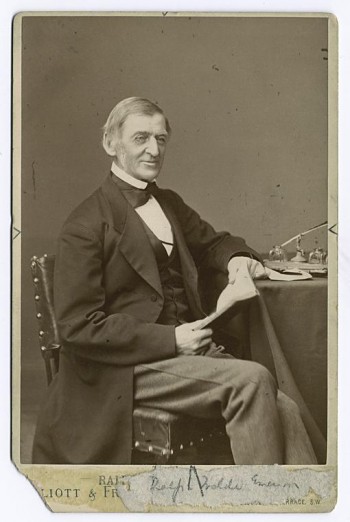

The maiden aunt of Ralph Waldo Emerson made no fame for herself in a lifetime that began just before the American Revolution and ended in the middle of the Civil War. Mary Moody Emerson spoke her mind, though, fearlessly and freely. In this fierce liberty she was not only being a good American, she was being a good Christian.

Rev. William Ellery Channing never suffered for want of anything. He lived in an era when the wealthy regarded laborers almost as a separate species, but he called himself a working man to show his solidarity with the new laboring classes of his early industrial age. He believed that all individuals, including slaves, deserved the freedom to think and act by their own best lights, and he believed this because of his Christian faith in what lay inside each soul and what potential all of God’s creatures could reach.

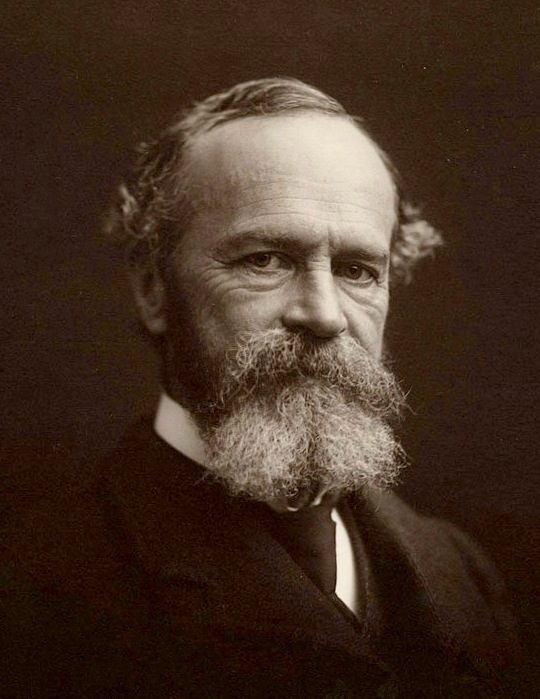

William James, the most important philosopher in American history, also wanted for nothing, but he never became a Christian. He did not appear to be much of a democrat, either, with his distaste for uneducated speech and his regard for European standards of excellence. Yet he professed to believe in a “religion of democracy” that took the sacred equality of all individuals as a postulate from which real human progress might flow.

The Scottish immigrant Thomas Davidson fell from Christian grace early in life while learning all he could about modern science, ancient and modern philosophy, human languages, religion, and culture. Yet he was more evangelistic than secular. The good news he wanted to spread was how free individuals interacting in all their diversity could make progress together, even Jews, even women, even workers in an age rife with prejudice of all kinds.

William Mackintire Salter, son of a minister, also fell from Christian grace as a young man despite his most earnest religious commitment. Actually, his earnestness gave him the integrity to face his growing belief that Jesus Christ was not the one and only uniquely divine being ever to be born. Salter became a post-Christian religious leader who called on the state to treat workers as equals with bosses during the industrial crisis of the late nineteenth century. Against the laissez-faire majority, Salter cried for social justice as sacred justice.

The social thinker and activist Jane Addams did more than cry for social justice—she lived for it. Rather than giving the poor what she thought they needed, she lived among them as she believed Jesus would have done. Through community, she built relationships that taught her what all humans share, a longing for pleasure and beauty as well as security and shelter and a sense of purpose in life. She connected workers and bosses, social scientists and politicians, educators and ministers, and philanthropists and activists from around the world. She wanted to make governments tend human needs and collective human needs drive global change.

The long cultural and intellectual lineage represented by these seven thinkers stretches back to classical liberalism, the political commitment of a society to replace coercion with consent. Their genealogy extends forward all the way to modern liberalism, the moral commitment of a society to the collective needs of all its members, regardless of their differences. Between the ideal of modern liberalism that has never been realized and the theory of classical liberalism that has never been dismantled—and amid contrary historical currents, like discrimination and exploitation that undermine both—these liberals and the rest of their intellectual family tree helped Americans and others think about why human beings ought to treat one another as equals who deserve to be free. This book is a history of that idea.

This history mostly took place in arguments, over dinner tables, beside campfires, aboard steamers, in the pages of journals, and inside people’s heads. Of all the inner lives depicted in this book, that of William James may be the most illustrative because he more than anyone tried to gather up the threads of ideas and values spun by his ancestors and to weave them into the new cloth of the modern era. The effort drove him to complete collapse at age twenty-four. He lost his strength, his energy, even his power of concentration as he squirmed beneath the oppressive weight of a life he now found loathsome. Dark clouds were all James could see as he struggled to reconcile what he thought was true with what he thought was right. Meanwhile, he could not make himself act at all and often wanted to die. This went on for seven years.

“Spinal paralysis,” James called his mental affliction. The phrase holds a lot of historical meaning. If the spine is physical, then the problem is material and the solution may be discovered rationally—through the use of reason, evidence, experimentation, and all the other empirical instruments of the Enlightenment, the intellectual transformation that originated in Europe and migrated, unevenly, around the globe. Beyond a doubt, James was a product of the Enlightenment who practiced the scientific method and heeded natural facts. This was true of everyone on his intellectual family tree. Yet most people think of the Enlightenment as a secularizing movement, spreading a loss of faith in religion along with its new faith in human progress. And there is nothing James and his kin cared for more than religion.

The spine is not only physical. Call someone spineless, say they have no backbone, and you are saying something about their character, something grave. Cowards are not manly. The weak-willed are not trustworthy. James worried so much about his spinal paralysis because he cared so much about his free will, and this value came not from the Enlightenment, but from the Reformation. Actually, free will is much older than the sixteenth century Protestant Reformation. An ancient Christian answer to the problem of evil—the problem of why bad things happen to good people when an all-good God is supposed to be all-powerful, a problem that bothered James although he never believed in that kind of God—free will is particularly important in the history of American democracy because of the role it played in the Reformation and the role the Reformation played in New England. Indeed free will has everything to do with the democratic principles of liberty and equality.

Although the first William James in America arrived after the Revolution, the roots of Jamesian thought lie not with this paternal grandfather but with New England Christians who did not even anticipate that such a war would ever come, yet whose deepest convictions helped make it possible. Heirs to the Puritan tradition, these Christians believed that their ancestors had crossed the Atlantic in devotion to liberty of conscience, or the divine right of private judgment, the idea that God creates every human being a moral agent endowed with free will, which it is each individual’s right and duty to exercise conscientiously in order to cultivate virtue and its ally, truth. New England Christians argued with one another over precisely what the truth may be—and they always had—but as the eighteenth century wore on, most of them came to agree that the British were violating the colonists’ essential liberty, which they understood in both religious and political terms. Their devotion to Reformation Christian liberty made New England patriots extremists in the colonies when it came to the cause of independence, but by the time the war arrived they had started to disagree with one another over a fundamental matter of their faith, the very nature of truth. One side, the side the founding father John Adams practiced, believed that the truth could be known in full to no human being, and that humility and open-mindedness as well as sincerity and candor were therefore fundamental characteristics of piety. These Christians became the first people in the world to call themselves liberals, by which they indicated their commitment to open-minded moral agency. The other side of the New England Christian debate believed that ultimate truth was contained in Calvinist articles of faith and ought to be spread evangelically. This side, although its commitment to Calvinism loosened over time, has been contending ever since that the United States is a Christian nation, meaning a nation founded upon an evangelical Protestant faith dubbed orthodox. The argument between these splintering halves of New England Christianity produced a novel turn in thought and culture, an American Reformation.

Up to now the American Reformation was hard to see for two main reasons. The first is the very myth of orthodox American Christianity produced by the evangelical side of the debate, a useful fiction in a country with a sizable Protestant majority but a guarantee of religious freedom instead of an established religion. This myth, adopted by scholars and popular commentators alike, equates religion with Christianity, Christianity with supernatural belief, and Christian belief with a particular faith in the special saving grace of Jesus through his blameless death and glorious resurrection. This evangelical kernel of Christianity had certainly been part of the Puritan tradition—and of other American Protestant sects as well as Catholicism—but the revival movement of the eighteenth century separated this kernel from other beliefs and practices that had grown up with those traditions, delineating the evangelical doctrine starkly so that it became the essence of faith. The myth of orthodox American Christianity gave rise to a distinction between head and heart, or the intellect and the soul, making any departure from so-called orthodoxy appear as a falling away from religion, a decline from faith, a crisis, a move of revolt or rejection or outright warfare on religion that inexorably brings on secularization, which measures value by the merely natural or material rather than the ultimate or divine and is widely associated with modernity. Christians who deplore secularization and humanists who applaud it have both found this myth useful, but lifting the veil of orthodoxy from the actual complexity of American religious thought reveals that the liberals who departed from this alleged orthodoxy did so in fidelity to their Christian faith rather than in spite of it.

The second reason the American Reformation has been hard to see is because of a myth some later liberals created. Actually, it’s Ralph Waldo Emerson’s fault. This son of a son of a son of a New England minister acted like he was making a complete break with his ancestral faith when he left the pulpit, but actually he left it on grounds of conscience, to develop his moral agency, to pursue virtue and truth as only he could see it. In other words, Emerson was an exemplary fruit of the American Reformation who did not fall far from the tree planted by his forefathers. But admirers of Emerson early in the academic study of American literature were snookered by his story about corpse-cold Boston Unitarianism and erected him king of what they called the “American Renaissance,” a cultural and literary movement purportedly free of superstition, dogma, and other stale accretions of America’s religious past. These scholars knew that Emerson’s father had belonged to a small intellectual fellowship in Boston that produced a monthly journal out of weekly conversation over “a modest supper of widgeons and teal,” as one such scholar put it in 1936, “with a little good claret.” Yet they had no idea that Rev. William Emerson and his friends practiced moderation for the sake of reason not only because they had absorbed Enlightenment ideas from Great Britain but because free inquiry paired so well with free will.

Looking at the historical contribution of New England as an American Reformation instead of an American Renaissance shows that a democratic approach to religion forged the real liberal tradition in America. The American Reformation began as an extended conversation among professing Christians whose basic premises were spare: the perfection of God and the moral agency of human beings. About everything else they argued. In the face of disagreements, liberals tried to maintain open minds and to believe in the possibility and desirability of progress—moral progress, human progress, and social progress dependent on each individual’s growth in conversation with other individuals, rather than in opposition to them, in a society that rises together if it is to rise at all. Liberals strove to keep their minds open to other people’s perspectives because they knew they were fallible, like all humans, which meant that their own opinions might be wrong, and because they believed that all humans also bore within some unique quality of the infinite divine from which others might learn. Human beings are essentially equal, profoundly equal, as fellow fallen creatures of the same perfect God. They need freedom in order to exercise their divine right of private judgment—to heed their sacred inner voices of reason and conscience and to evaluate others’ opinions—and they have a duty to use this freedom to express their perspective on truth as faithfully as they can. The American Reformation produced not only Christians who called themselves liberals, but also liberal intellectual culture, in which both listening with humility and speaking with integrity are acts of piety.

Liberals were initially concentrated in New England, the most scholarly and pious—scholarly because pious—community of discourse in America, but many of their main talking partners were British. Their conversation always reached across the Atlantic. Liberals also stood squarely between the two other most powerful intellectual cultures in what became the United States, the revived Christians of the wider American populace and the rational elites of urban centers. Instead of elbowing out these two groups, their fellow Reformation Christians on the one side and their fellow acolytes of reason on the other, liberals connected them, holding hands with each and translating key terms and critical concerns for the goal of important compromises like declaring independence from Britain and adopting a Constitution for nationhood. The conversation liberals carried on over the eighteenth century and across the nineteenth created such a powerful turn in modern thought because they were moderates, because they were central interlocutors, because they balanced confidence in their own point of view with a commitment to considering other points of view. Most important, their very particular Christian perspective gave them the tools to create, over a long span of intellectual and cultural development, a universal platform for mediating human difference that must be called secular although it is rooted in religion.

“Secular” and “liberal” are among the most loaded terms in the English language, carrying so much intellectual freight that no one can conscientiously use them without explaining how they are meant. Conscientiousness, of course, is just what the religious liberals of the Revolutionary era and beyond most valued. Freely chosen action “upon mature deliberation,” as they would have put it, is right conduct for a moral agent. But liberals were not secular if secular is to mean something somehow opposing religion, or devoid of religion. Far from it. Moreover, they really did not know anyone who truly opposed religion (churches were another matter). The lightest touches on religion came from people like Thomas Jefferson, who conscientiously trimmed the Christian Bible to dimensions of his liking; he certainly was a moral agent who used his reason and his conscience. Yet Jefferson spent much less time contemplating infinity than John Adams, his comrade, foe, and friend. This put Adams comfortably—or rather uncomfortably—between Jefferson and Samuel Adams, a cousin of John’s who adhered to a much more evangelical, uncritically biblical Christianity and who therefore cannot be called much of a liberal because once one becomes a liberal of any type, one becomes a critic, actively scrutinizing every possible article of belief or value “objectively,” with an impartial eye and a mind buoyed by the reference point of perfect divine truth—which is, unfortunately, invisible, beyond the reach of human senses. Jefferson thought less about the invisible than either Adams did, while being a rational critic; the Adams cousins shared more than a last name; all three could be mapped onto a continuum devised from what scholars refer to by the terms republicanism, political liberalism, and Christianity, as well as several other key words of the modern period, such as civic humanism, tolerance, individualism, rights, and perhaps even modernity itself. John Adams may be the most representative figure of the early American Reformation because he fell most stoutly in the middle of all these markers and because he engaged in active conversation with the biggest variety of representatives from groups who leaned more strongly in one direction or another. He was “secular,” then, insofar as he believed the public sphere ought to field all viewpoints. Insofar as Adams was “liberal,” he both stood up for his own point of view and, acknowledging its partiality, remained open to revision. Each of these positions reflected his Christian conviction and piety.

Liberals were ubiquitous in American public culture across the nineteenth century, yet always a numerical minority. Wary of party spirit, they were Federalists and then they were Whigs and then Republicans, and then, at the end of the century, they became Mugwumps who declared themselves independent thinkers while still mostly voting Republican. It is tempting to claim they became Democrats in the twentieth century, but by then the American Reformation was over and the conversation changed. Although liberals favored a consistent range of social and political positions over this long period, their most fundamental commitment was to their approach to truth. Against those who believed they already knew what was right and pursued policies to reflect this fixed truth, liberals advocated for truths they recognized as provisional and incomplete, and they were committed to listening to contrary opinions for any possible truths the opposition might hold and working dialogically toward consensus. At least in theory. This open-ended conception of truth was born of Christian humility in the eighteenth century, when the American Reformation tied equality and liberty to the human soul at the same moment these root concepts were being tied to American democracy. The democratic idea gradually became not only a political system but also, among liberals, a universal ideal for the social practice of treating others as equals, a “religion of democracy.” The commitment to universal moral agency was what it meant to be liberal from the early republic into the twentieth century, the period covered in this book. Only with the New Deal did the word “liberal” come to indicate a political commitment to a federal government responsible for social welfare, a commitment that was indeed produced by the long conversation among liberals with one another and their ever-changing opponents but that, once held as a fixed truth, was no longer liberal in this historically grounded sense of the term.

Two subtle ironies surround the history of this religion of democracy. The first is that the liberal Christians who set its wheels in motion acquired a reputation for softening their religion into mere morality, as though to focus on ethics were to focus on something other than real religion. From the liberal point of view, virtue is the fruit by which true faith is known. This charge is a by-product of the myth of orthodox Protestant Christianity, made especially potent by what happened during the middle period of the American Reformation. When Romantic ideas about universal inner divinity arose amid an exploding literary canon that was globally inclusive for the first time, Christianity’s claims to exclusive truth started to look like hubris to some liberals. How could an open-minded moral agent be so sure a Hindu did not know God? Transcendentalists and others then left the Christian fold without really rejecting Christ. To the surprise of many faithful devotees of the American Reformation, liberal Christians started battling their own intellectual and cultural progeny, post-Christian religious liberals who discovered the divine not only in the Christian Bible but far beyond it. This post-Christian turn marked the end of the American Reformation and the beginning of the religion of democracy in which no tradition could boast unique revelation but all individuals bore unique inner divinity.

The second irony around this history is that the chief sin of which these post-Christian religious liberals were accused was of discarding ethics altogether by indulging in a moral relativism that verged on nihilism. The charge is delivered with moral indignation if not outrage, as though giving credence to other points of view were not itself a moral commitment with venerable Christian roots. Tolerance looked like apathy to critics and piety to liberals.

Just as there is more than a grain of truth in the myth of orthodox Protestant Christianity in America, there is more than a grain of truth in these criticisms of liberal morality, despite their logical incompatibility, but nuance matters. At least it did to liberals. When Calvinists said that humans were utterly and innately sinful, liberals rejoined that humans were instead subject to sinfulness, prone to sin, the very thing religion is supposed to mitigate. This then highlights another film across this history: the one trend in the history of American religion to resist the myth of orthodox Protestant Christianity is the history of liberal religion, which includes post-Christian, metaphysical, spiritual-but-not religious, and other nonevangelical forms of religion in the genuine and robust history of religion in the United States—and then goes on to treat liberal religion as though it did away with sin, and as though liberal religion had nothing to do with politics. This interpretation is understandable. Liberals had pushed back hard against the grim Calvinist insistence on the utter determinism of human sinfulness. Then the liberals of the nineteenth century were succeeded by some extremely optimistic and often politically irrelevant religious liberals in the therapeutic atmosphere of the twentieth century. “You are a child of the Universe,” said one famous credo, reassuring an affluent public that “no doubt the universe is unfolding as it should.” No problem of evil there. In the nineteenth century, however, religious liberals both Christian and post-Christian emphasized the positive in order to pull behavior out of its heavy habitual path toward the negative for reasons never unconnected to the public sphere. And they did this by focusing Christian practice—and then post-Christian religious practice—on mental development, the training of the human mind.

Amy Kittelstrom an associate professor of history at Sonoma State University, specializing in nineteenth-century American thinkers and their sociopolitical context. She is a past fellow of the Center for Religion and American Life at Yale, the Charles Warren Center at Harvard, and the Center for the Study of Religion at Princeton.