How the Model of Money Laundering Can Help Us Understand Abuse within 3HO

Philip Deslippe

In April 2016, an elderly woman in China was photographed kneeling and burning incense before a statue that she assumed was the deified third-century general Guan Yu, but was actually of Garen, a character from the video game League of Legends being used to promote a local internet café. Nine months later, a Brazilian grandmother learned that the statue of Saint Anthony of Padua that she prayed to every night for years was actually of the elvish Lord Elrond from a movie adaptation of J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings.

Both of these stories went viral as humorous and harmless cases of misplaced devotion, and many online commentators offered responses to them that were both kind and non-dogmatic. If someone was sincere in their devotion, they argued, does it really matter if the object of that devotion was not exactly what it was supposed to be? A much more serious and profound shift occurs in the wake of revelations of abuse within a spiritual community. To learn that a religious or spiritual authority abused those under their care is an acute violation of trust with few parallels.

Revelations of sexual abuse have emerged in a wide range of religious communities—Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, Muslim, and Buddhist—but seem to be especially rife within the yoga world which has seen scandals involving sexual assault and misconduct involving leading figures including, but not limited to, Krishna Pattabhi Jois, Amrit Desai, Kausthub Desikachar, Swami Rama, Swami Satchidananda, Bikram Choudhury, and Swami Vishnudevananda. The question of which prominent yoga teachers have been involved in scandals of abuse and misconduct seems to have given way to a new question that is both hyperbolic and yet all too realistic: which prominent yoga teacher has not been involved in scandals of abuse and misconduct?

Within this ignoble list is the late Yogi Bhajan (1929-2004). Born Harbhajan Singh Puri in modern-day Pakistan, Yogi Bhajan was a former customs officer at New Delhi’s Palim Airport before coming to Los Angeles via Canada in late-1968. He found an eager audience of young spiritual seekers and began teaching them a form of yoga he called Kundalini Yoga that he claimed was ancient and previously secret. His students spread his yoga throughout the United States and Europe, lived communally in ashrams, founded businesses, and started converting to Sikhism. By the time of his death in 2004, the Healthy, Happy, Holy Organization or 3HO that he founded 35 years earlier had become an umbrella over a vast and unique empire of New Age spirituality and yoga, Sikhism, and capitalist enterprises that included companies like Yogi Tea and Akal Security.

Controversy and criticism shadowed Yogi Bhajan from his arrival in the United States. During the late-Sixties, talk of his abuse and misconduct spread by word-of-mouth among former students. In the late-Seventies, a book-length criticism of Yogi Bhajan titled Sikhism and Tantric Yoga was published at the same time an article in Time Magazine criticized his “synthetic Sikhism.” The Eighties and Nineties saw numerous lawsuits against Yogi Bhajan for sexual and psychological abuse and the arrest of numerous members of 3HO for a host of criminal activities, all of which were reported in newspapers. For several decades now, there have been online forums for ex-members of 3HO that have hosted discussions of the misdeeds of Yogi Bhajan and abuse within 3HO boarding schools at length and in great detail.

In early-2020, a self-published memoir by one of Yogi Bhajan’s former personal secretaries, Pamela Dyson (known as Premka in 3HO), was released and recounted her abusive sexual relationship with him. A social media page initially dedicated to promoting and discussing the memoir quickly became a forum for several other women to tell their own stories of abuse at the hands of Yogi Bhajan. Zoom meetings within 3HO were inundated with second-generation members telling their own stories of abuse by Yogi Bhajan and within 3HO institutions. An investigative report was commissioned by the Siri Singh Sahib Corporation, and its findings released in August concluded that “more likely than not” Yogi Bhajan repeatedly carried out a wide range of abuses for decades including rape, sexual harassment, and grooming of underage women.

Denying, Rejecting, and Calculating the Harm within 3HO

Over the last year and a half, the widespread revelations of abuse and misconduct by Yogi Bhajan have created three main groups of members and ex-members of 3HO. The first group could be described as double-downers: those who have denied or dismissed claims of abuse and reaffirmed their beliefs in their late spiritual leader. They drew their reasoning from 3HO teachings and Yogi Bhajan’s lectures as they discredited those making accusations against Yogi Bhajan as “slanderers” and placed Yogi Bhajan beyond comprehension or reproach. The report by An Olive Branch included quotes from some of these supporters who claimed that Yogi Bhajan was “a divine master… like Christ or the Buddha” and “operating from a different level of consciousness.”

At the other end are those who completely rejected 3HO and Yogi Bhajan after becoming aware of abuse and misconduct. Many stopped teaching or practicing Yogi Bhajan’s Kundalini Yoga altogether, and some dramatically filmed themselves burning their old yoga manuals and pictures of their former late teacher. Some not only rejected Bhajan and 3HO but saw their identities as Sikhs as being entangled with an indefensible teacher and organization, and so they cut their hair, let go of the 3HO version of Sikh dress or bana, and changed their surnames from “Khalsa” to those of their birth families.

In-between these two extremes are those who engage in what I have called “harm calculus,” a process by which members and ex-members of a spiritual community try to assign value to the harm done by a spiritual teacher or within a spiritual community and measure it against the perceived good created by that teacher and/or community. Most often, harm calculus is used to provide a rationale for members or the community at large to move forward and continue much of what they had previously done, but in a way that can encompass new revelations of abuse and misconduct while still remaining acceptable to the individual or organization.

For those involved with 3HO, the main calculations of harm have been done to continue the practice and teaching of Yogi Bhajan’s Kundalini Yoga. With lucrative teacher training programs, along with organizations and individual careers dedicated to this particular form of yoga, there has been a pragmatic financial incentive to keep the yoga going. Yogi Bhajan’s once central role has been minimized, and individual teachings and 3HO organizations like the Kundalini Research Institute have instead centered the personal experiences of Kundalini Yoga practitioners, the pragmatic benefits and alleged scientific validity of the yoga, and foregrounded people of color and social justice issues in what some have termed “woke-washing.”

These three main perspectives of former and current members all rely on seeing Yogi Bhajan and 3HO in absolute terms. For double-downers who reject all claims of abuse, Yogi Bhajan and 3HO are unsullied and unambiguously good. For those who reject Yogi Bhajan, his teachings, and the organization he founded, it is all a “cult” or “con,” and an association with any of it is problematic.

Those who engage in harm calculus divide up Yogi Bhajan and 3HO into aspects that are discreetly good and bad. Yogi Bhajan was bad, but the yoga he taught or the conversions to Sikhi that he inspired were good. There were bad actors or elements, but they were limited in number or isolated to particular parts of the organization (such as an “inner circle”) and should be considered separate from what was good or from those with sincere intentions. But a close inspection of Yogi Bhajan’s teachings alongside his abuse and misconduct shows that his teachings were often inseparable from his misconduct and that his teachings often facilitated the abuse and misconduct.

One example of how intertwined these two elements are is Yogi Bhajan’s teaching that when a woman is pregnant the soul of the child enters the womb on the 120th day after conception. Within 3HO it has become a custom to celebrate the expecting mother on this day, although the origins of this concept and practice are described in vague terms as “ancient” or “yogic,” there are no parallels to it beyond Yogi Bhajan. The other part of the concept, that before the 120th day there is no significance to abortion because the fetus is simply “a piece of flesh” and the mother “can do whatever you like,” makes sense in light of what was revealed in the report by An Olive Branch: that Yogi Bhajan would force women he had impregnated to have abortions and would exercise “control over procreation” with other female followers.

Another example is with Yogi Bhajan’s claimed titles. In 2012, I wrote an article for the academic journal Sikh Formations about the creation of Yogi Bhajan’s yoga that suggested, with corresponding evidence and documentation, that his claims to being a Sikh religious authority, yoga master, and singular holder of a tantric lineage were spurious. Within a conclusion that was perhaps too conciliatory, I suggested that maybe the experience of practitioners was “the most honest and fruitful vantage from which to view” Kundalini Yoga and that individual experience could exist alongside Yogi Bhajan’s spurious claims.

As the statements from survivors posted online and included in the report by An Olive Branch make clear, these titles were not simply ornamental but played a critical role in Yogi Bhajan’s abusive and criminal behavior. Many felt obligated to obey the religious authority of the “Siri Singh Sahib,” thought that they could not understand the motives of an enlightened “Master of Kundalini Yoga,” or were enticed with the possibility that he would pass the mantle of “Mahan Tantric” on to them.

Neither of these three positions—the double-downers, those who reject 3HO and Yogi Bhajan completely, or those engaging in harm calculus—can fully encompass the complexity of 3HO or the systemic nature of the abuse carried out by Yogi Bhajan who used businesses, schools, spiritual teachings, and the power of his students’ personal lives, in matters of marriage and child-rearing to dress and personal hygiene, to facilitate his grooming, exploitation, and abuse.

Even more confusing is how in the light of revealed abuse, the reality of Yogi Bhajan and 3HO seems to have been completely opposite of their portrayal to students and the public. Yogi Bhajan offered himself to his students as helping provide guidance away from a decadent American society which one student described in the September 1977 issue of Sikh Dharma Brotherhood as consisting of “political, social, and economic corruption, sexual orgies, promiscuity, (and) de-humanization… where money and sex are two triumphant gods.” Each one of these claims could be applied to Yogi Bhajan.

Money Laundering

To see the abuse carried out by Yogi Bhajan as an aberration within a legitimate religious system would misread how that abuse was carried out in ways, unlike a religious system. To see the abuse as simply part of a larger con or to fall back into standard descriptions of 3HO as “a cult” is also a misreading of how 3HO operated, and the pointing towards “brainwashing” allows many who were complicit in abuse to avoid basic responsibility for the abuse that occurred.

Although unusual, I would suggest that one comparative model that can describe abuse within 3HO is money laundering, and in particular, the role of front businesses in money laundering operations. Money laundering is the solution to a problem that many criminal operations face regarding the money they generate. They are unable to openly declare the source of their revenue or pay taxes on it, and so spending money carries the risk of exposing the illegality of what they do or opening them to prosecution for tax evasion.

In simple terms, money laundering is the process of concealing the source of illicitly gained money and rendering it legitimate. This is usually done through a three-step process of placement (moving illicit money into a lawful financial system), layering (combining illicit and lawful funds), and integration (reintroducing the combined illicit and lawful funds into a legitimate asset or financial system). A central component to all three steps of money laundering is a front business, or a legal operation that illicit money can be put into and that then facilitates the layering and integration of that money.

A simple example of money laundering would be a drug dealer who uses the money gained through drugs to purchase a pizzeria. By using (and inflating) the revenue generated by the pizzeria, the drug dealer has a legitimate reason for their wealth, can pay taxes on that money, and is free to openly spend it.

According to interviews I conducted with two of his first hosts in Los Angeles, Yogi Bhajan arrived in the United States not on a spiritual mission, but with hopes of starting an import-export business and avoiding a woman he impregnated in Canada. From Dyson’s memoir, we know that he was sexually assaulting women from the very beginning of his time as a yoga instructor. It is not difficult to see his actions, combined with his constructed claims to be a yoga master, as a form of placement: an abuser finding a role that facilitated and obscured that abuse like a criminal moves money into a legitimate business.

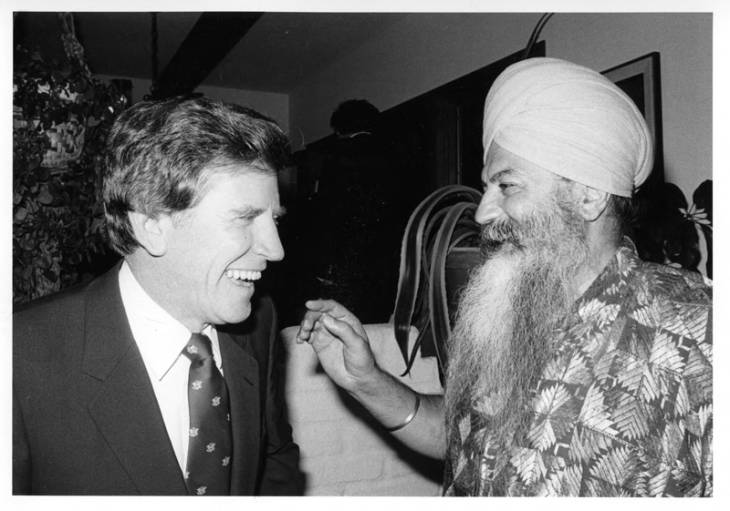

The constant claiming of titles by Yogi Bhajan, his defining of his own unique role as a spiritual leader and strict, incomprehensible “Saturn teacher,” and the endless photo-ops and association with various religious and political leaders could all be seen as a form of layering that allowed for a respectable religious cover to his person and behavior. Integration would occur as Yogi Bhajan used his position and the infrastructure of 3HO to engage in abuse and misconduct, both in private and in the open. Through the systems he established, Yogi Bhajan could wear floor-length mink coats and gaudy jewelry and be seen as spiritual, not corrupt, or scream at and kick students and be seen as wise and compassionate, but not angry and abusive.

It is common to joke that businesses that are run down, have few customers, and have little visible revenue are fronts for money laundering. However, the more viable a front business is, the more efficiently it can facilitate the laundering of money and provide cover to the criminal operation behind it. The legitimate support the illegitimate in money laundering; the two are not opposed to each other.

While there were certainly people within 3HO who knew of Yogi Bhajan’s abuse and misconduct, and some who actively aided it, the systems that facilitated that abuse would not have been possible without also having members believe in them. The summer camps for women that provided Yogi Bhajan a venue for grooming and abuse, for example, could only happen with a majority of attendees believing that they were doing something good and spiritual by attending, and encouraging others to join them. This is perhaps one of the most complicated and difficult elements of unraveling the abuse and misconduct of Yogi Bhajan and 3HO: that the sincere beliefs and practices of many within 3HO were also helping to fund, facilitate, and protect crime and abuse. Naivety and complicity easily co-existed.

When I first read about the efforts to groom a child of ten and then sixteen years old through shopping sprees and Chanel dresses, I immediately wondered where that money came from, and if some of it came from the ten percent of their income that Yogi Bhajan’s students dutifully offered to him and his organization as “Dasvandh,” a twisting of the traditional Sikh practice of literally giving “a tenth part” of one’s earnings to charity and the community. Similarly, the Los Angeles-based Guru Ram Das Enterprises, one of 3HO’s “dharmic” businesses that were staffed by low-paid students and later acknowledged by numerous former employees as a fraudulent telemarketing boiler room, was used to maintain a slush fund for entertaining guests and providing services for Yogi Bhajan and his personal secretaries.

There were pragmatic reasons why some of those who suffered abuse by Yogi Bhajan and within 3HO did not leave. Many had their families, friends, jobs, as well as their spiritual aspirations tied up with the group, and members of the second generation of 3HO who were born and raised in the group, and were often children when they were abused, lacked the basic resources and autonomy needed to get out. One common barrier throughout Yogi Bhajan’s life and after his death was the wall of denial survivors faced from family and community members who refused to believe that such things were possible or enfolded them back into Yogi Bhajan’s teachings like so many “bounded choices.” Sincere belief surrounded and protected Yogi Bhajan like so many of the students he placed on his personal security detail.

Conclusion

In a 2016 piece for Religion Dispatches, Professor Andrea Jain cautioned against calling the settlement of a sexual harassment lawsuit against Bikram Choudhury (among several other claims and lawsuits of rape and sexual harassment against him) another “guru scandal.” According to Jain, “corruption is found in all forms of authoritarianism” and “the assumption that corruption is somehow inherent in (the guru) model betrays an orientalist stereotype of South Asians, their religions, and other cultural products as despotic in contrast to white, so-called democratic religions or cultures.” The consistent inclusion of non-South Asians within “guru scandals” in the United States for over a century—from William Latson and Pierre Bernard in the 1910s to Jon Friend, Manouso Manos, and Ruth Lauer-Manenti in recent years—shows that the responses are not entirely reducible to simple racist, xenophobic, or orientalist views towards South Asia.

One example cited by Jain of the erroneous assumption that the “guru model” is problematic for its inherently undemocratic tendencies” was the 1993 book The Guru Papers: Masks of Authoritarian Power by Joel Kramer and Diana Alstad. I interviewed Kramer and Alstad in 2011. In the course of our hour-long conversation, they discussed how the premise of The Guru Papers was not just a matter of abstract theorizing or stereotyping, but was built upon a large number of testimonies they had received from friends and informants who had directly experienced abuse from various spiritual teachers, including Yogi Bhajan.

Kramer and Alstad did not simply rail against fraudulent spiritual leaders, nor was their thesis only that the type of unrestrained spiritual leadership held by gurus in the West was an extreme and emblematic form of authoritarianism. They argued that gurus held a uniquely unrestricted form of power that was reinforced by the assumption that they were “totally immune from the corruptions of power.”

I was quoted for an article in Los Angeles Magazine that Yogi Bhajan “will be remembered like a Harvey Weinstein or a Jerry Sandusky of yoga,” but there is something distinct about the revelations of abuse carried out by Yogi Bhajan. Few people laud the merits of the films produced by Weinstein or the coaching of Sandusky isolated from their criminal behavior or attempt to justify their actions. Who would dare suggest that Harvey Weinstein was attempting to make Salma Hayek a better actress through his abuse, or that Jerry Sandusky was a different person as an abuser than as a coach? But that absurdity is common with those who continue to espouse the yoga taught by Yogi Bhajan.

The abuse carried out by spiritual leaders such as Yogi Bhajan is exploitation done by someone who by their ability to define their actions can constantly claim abuse and misconduct to be something other than what it is: mistreatment as affection, abuse as upliftment, or suffering in the real world as a fulfillment of unseen karma. Some of the scholars who studied 3HO in its earliest years noted what I would come to learn through hundreds of conversations and formal interviews in a dozen years within 3HO and another dozen years studying it from the outside: that an inordinate percentage of people chose to enter 3HO and not some other path in life because they wanted to escape or heal from previous abuse and trauma. In a cruel irony, the dysfunctional childhood home, the rage-filled alcoholic parent, or the sexual abuser were replicated in the 3HO lifestyle or the person of Yogi Bhajan.

The sense of confusion and betrayal by many of these people has been shared by other current and former members of 3HO as the abuse and misconduct of Yogi Bhajan has been further revealed over the past year. The gulf between the outward claims of Yogi Bhajan and the reality of his behavior, and the complicated ways in which his organization and the sincere intentions of various members aided his abuse would seem to have few parallels, but it is not unlike learning that a business was actually a front used to launder money for a criminal.

Philip Deslippe is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He has written articles for academic journals including Amerasia and the Journal of Yoga Studies, and pieces for popular outlets including Tricycle, Yoga Journal, and Scroll.in.