David Feltmate

2017 was a whirlwind and a nightmare for some of us living in the United States. In the wake of Donald Trump’s political victory and a rise of nationalist and racist rhetoric—not to mention Nazi rallies and murders in American cities—the year required an exhausting series of political and ideological battles. As we move into 2018 and the mid-term elections, people with different political ideologies than the current administration have a new hope and purpose. Electing officials who will enact progressive policies that will avoid the absolute worst of global climate change, domestic poverty, and protecting the social safety net seems to be the new agenda and news organizations, political activists, and social media conversations are turning towards November 2018 while looking back to November 2016. It is easy to get caught up in the emotional pressure of this moment and while I think that people should be politically engaged and thoughtful about the policies they want to see implemented, it is important to keep some sober thoughts in mind that studying religion and popular culture can help reinforce.

Elections are civil religious rituals. As Jeffrey Alexander so beautifully demonstrates in The Performance of Politics (Oxford University Press, 2008), candidates find ways to fit into national discourses that are built upon significant symbols. Of course, in a democratic society those symbols are interpreted differently by divergent groups and certain symbols are emphasized over others depending on peoples’ historical and social conditions. 2017 was filled with stories about white working-class voters who ostensibly propelled Trump to victory. Reports about unemployed coal miners, factory workers who saw their jobs outsourced, and angry white people who thought they were getting the bum’s rush filled newspapers, online magazines, and other venues. Underlying all of this discussion was an existential question: How could this happen? Symbols of a white nostalgia had seemingly destroyed the vaunted Obama coalition of young and multicultural voters who had propelled the forty-fourth president to two victories. Somewhere a pendulum had swung, but the national panic also treated this as a new era, an “Era of Trump.” We were through the looking-glass.

Elections are civil religious rituals. As Jeffrey Alexander so beautifully demonstrates in The Performance of Politics (Oxford University Press, 2008), candidates find ways to fit into national discourses that are built upon significant symbols. Of course, in a democratic society those symbols are interpreted differently by divergent groups and certain symbols are emphasized over others depending on peoples’ historical and social conditions. 2017 was filled with stories about white working-class voters who ostensibly propelled Trump to victory. Reports about unemployed coal miners, factory workers who saw their jobs outsourced, and angry white people who thought they were getting the bum’s rush filled newspapers, online magazines, and other venues. Underlying all of this discussion was an existential question: How could this happen? Symbols of a white nostalgia had seemingly destroyed the vaunted Obama coalition of young and multicultural voters who had propelled the forty-fourth president to two victories. Somewhere a pendulum had swung, but the national panic also treated this as a new era, an “Era of Trump.” We were through the looking-glass.

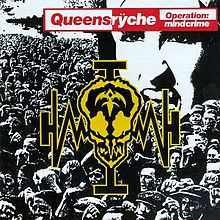

I spent much of 2017 kicking around an idea for an article about how the band Queensryche’s 1988 album Operation: Mindcrime was prophetic. Mindcrime is a story about how a young drug addict and social outcast named Nikki becomes a hitman for a revolutionary group and eventually ends up in a mental institution. Every time that I listened to the album, lyrics resonated with the larger themes of white working-class alienation that I was being told were the reasons for Trump’s victory. Songs such as “Speak,” which has a chorus spoken from the mysterious Dr. X who appears on television and tells people to join his revolution: “Speak to me the pain you feel/ Speak the word/ The word is all of us” and “Revolution Calling,” with lyrics such as “Got no love for politicians/ Or that crazy scene in D. C./ It’s just a power mad town/ but the time is ripe for changes/ There’s a growing feeling/ That taking a chance on a new kind of vision is due/ I used to trust the media/ To tell me the truth, tell us the truth/ But now I’ve seen the payoffs/ Everywhere I look/ Who do you trust when everyone’s a crook?” contained ideas that were everywhere in 2016 and 2017. Every time those songs would come on my mind would make connections to allegations of “fake news” and chants of “Drain the swamp!” When the song “Spreading the Disease” states that the “the one percent rules America” the last six years of post-Occupy Wall Street sloganeering echoes through my head.

Surely, I thought, this 1988 album was “ahead of its time.” Was it prophetic? Certainly it spoke to this moment. A 2016 Gallup Poll showed that trust in news media reached a new low that year. Only thirty-two percent of Americans had a “Great deal/Fair amount” of trust in the news. Among Republicans, that number sank to fourteen percent.[1] Partisan news reporting has become expected, and with that, the false equivalency that argues that since some news organizations are biased all are biased. This lack of trust can lead to some people just giving up trying to weigh different perspectives and resort to reading material that feeds their existing predispositions. We no longer trust the media to tell us the truth and “fake news” has become a standard part of our lexicon, used to dredge up anger at those who report things we do not like as much as it is to target factually untrue claims in news media. Trump’s entire campaign was based on “Making America Great Again,” a slogan that spoke to a variety of beliefs people held, but which never became a defined set of standards that could be critically engaged. That sense of “Speak the word/ the word is all of us,” however, was a powerful force for a candidate who was able to say what people at his political rallies were thinking and feeling. Whether or not you agree with the sentiments that things were better in the past, that political correctness has ruined our culture, and that immigrants and non-heterosexuals are destroying the fabric of society, there were a significant number of people who did and who voted in the right states (since Trump won through the electoral college rather than the popular vote). Unequal distributions of wealth continue to grow at an expeditious pace, with us now talking about not only the one percent, but the 0.01 percent of people with exorbitant concentrated wealth and their resulting power. Queensryche had, it seemed, predicted the emotional state of 2016 and the 2017 aftermath. After all, a disaffected killer for a new political order seemed particularly relevant on August 12, 2017 when James Alex Fields, Jr. was arrested and charged with second-degree murder of Heather Heyer, five counts of malicious wounding, three counts of aggressive malicious wounding, and one count of hit-and-run after he drove his car into a crowd of people protesting the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, VA. The rally was one of the largest white nationalist gatherings in recent history and turned violent. For a segment of the population, this was a moment in time when they felt emboldened to let their beliefs turn into violent action. Such acts are political and religious; they are done collectively to reorient society around a vision of an unseen order, in this case an unseen order in which straight white men are socially and physically dominant and entitled to use force to maintain their social supremacy.

Conceptually, prophecy seemed like a relevant term. Human beings have long tried to predict the future and foretell of things to come. From consulting oracles and cracking turtle shells to the long history of interpreting contemporary events through the biblical book of Revelation, we see patterns connecting significant symbols from the past with a selective reading of today to predict the future. Sometimes our predictions are relatively correct, sometimes they are not. Rarely is somebody one hundred percent correct about what will happen in the future, although that does not stop us from prognosticating. Reading the tea leaves with works of fiction, which speak truths in metaphors that can be applied in multiple ways as various circumstances dictate, is particularly dangerous. This is why I was wrong to think of Operation: Mindcrime through the lens of prophecy. It is not prophetic. It is a fictional work that was produced thirty years ago that can help us to see a different, more sobering pattern of human behavior if we let it.

History is a fickle teacher. Things happened, but how we conceptually turn those things into events and then explain their significance for people in the present is always a labor of selective interpretation. Yet, my mistaken thinking about Mindcrime as prophetic instead of a work of its time led me to realize a bigger problem that I was dealing with. The debate about the Trump administration and our current political climate is the question of how “historic” it is. “Historic” is used to signify how odd, important, momentous, and most of all unique this bounded moment in time is. At this point, a cliché that my mentor, Douglas E. Cowan, used to preach comes to mind: “Avoid u-turns. Nothing is universal or unique.” Claiming that Mindcrime is prophetic would have enabled me to claim that it was somehow unique among other works of popular culture; a visionary glimpse through the fog of future possibilities to settle upon a revelation that would be validated in time. We should not see it as such, instead, if we take Mindcrime as a product of its time we see that the band and their former lead singer Geoff Tate were engaged in political commentary about alienation, urban violence, and government corruption during the Reagan administration. The commentary that the band was making in 1988 was a product of its time.

What I realized is that if this work is not prophetic then perhaps the framing of the “era of Trump” had subtly corrupted my ability to think clearly with a historical imagination. We should not be looking at this moment as somehow unique. In fact, it contains far too many similarities with past eras. There is a sense that political gains from the past fifty-years may be lost, but this has been a theme of going back almost forty years. Reagan conservatives lashed out against people who received state benefits and tried to enforce heterosexual marriage as a solution to poverty—which was eventually enshrined in the Clinton-era Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996. Globalization and the outsourcing of jobs paved the way to urban and rural poverty and the hollowing out of the American working and middle classes. “Wars” were waged on drugs and terrorism and the racism which has long characterized American society continued to manifest itself in different ways; whether it became the association of the word “urban” with “black, poor, and violent in inner cities” or the fact that groups exist organized around racial hatred and a willingness to use violence to further their goals. In this world, the question of where one belongs and what makes for a meaningful life is thrown wide open and there has been a sense of the game being rigged for a long time. The mindcrime that we risk making in the “Trump era” is to think of this as a distinct, unique era in human history, rather than another twist in a long and ongoing story about people fighting over who and what continues “America.” We further risk misunderstanding how we use social structural factors and institutional structures to create ideological laws to try to turn our moral visions of a good society into policy that tries to force people into living within that vision. Politics is religious, but one thing that religious traditions can do is get us to think that the long arc of history leads to this moment and that our actions have long-term cosmic consequences even though this time is unique. Instead, we should take a sobering view from history that this has happened before and people responded. They made change happen. Trump’s win was one more moment in history where people will have to respond, but that future is not written and the emotional sentiments that were attributed to fueling that victory are not new.

There is a sense of immediate panic in the wake of Trump’s victory that separates people from working on the deep problems that have caused alienation in the United States since the 1980s. Scholars such as Kelly J. Baker have warned us that Nazis have worn suits for a long time; Robert Reich and Thomas Piketty have reminded us that globalization and the concentration of wealth is international, manufactured, and ongoing regardless of who is in power; and a bevy of scholars and public intellectuals—most notably Ta-Nehisi Coates—have continued to speak about racism’s ongoing structural implications for the United States. Yet, news networks focus daily on Trump’s faux pas, on contemporary debates in Congress as if they do not have decades (if not centuries) of history, and the latest hot-takes. The hot-take might be the greatest mindcrime of all since it fuels a moment-by-moment reaction that allows us to forget the larger patterns of which these events are but a tile in the mosaic.

My mistake reminded me that our thinking and analysis of any moment can be corrupted by the emotional highs and lows that it elicits—especially if other people are reacting with vigor. Even if the Democrats win in the mid-term elections the long arc of inequality which was started in the 1970s and 80s (and entrenched with the Thatcher and Reagan governments in the UK and USA), institutionalized structural racism that characterizes the United States’ social life and organizations, and global climate change will not cease without people learning from the past and figuring ways to learn from our ancestors’ mistakes. We should not see our predecessors as prophets, but treat them as people speaking a truth about corruption that is analogous to our time. Interpreting the actions of people in the past by asking how they dealt with situations, for good or ill, and making plans with well-articulated values and a sense of what is possible would be the best thing for all of us, but we cannot do that if we continue to succumb to an intellectual environment that asks us to react and not reflect.

Operation: Mindcrime ends with Nikki in a mental institution lamenting the murder of the nun, Sister Mary, and not recognizing himself. Trapped in his own realization that he made the wrong choices he has no hope and nowhere to go. Lest we react to our own time as a unique moment in history and look to the past as prophecy rather than precedent, we should take a warning from Nikki as he reflects on his life in his cell from the album’s conclusion “Eyes of a Stranger.” Now that he has killed Mary and has nobody, every time he sees himself Nikki knows that all that is left for him are “Straightjacket memories, sedative highs/ No happy ending like they’ve always promised” because “People always turn away/ From the eyes of a stranger/ Afraid to know what/ Lies behind the stare.” Reacting selfishly to the present situation and without a view to how collective problems require collective solutions Nikki did not learn the lessons of history and could not plot a new direction. He put his faith in a selfish tyrant. The story is a metaphor, but it continues to resonate as a powerful narrative precisely because the themes that shape Operation: Mindcrime continue to shape our world. If we learn to see them as a useful way of thinking past what seems like the uniqueness of this moment, and recognize that this piece of popular culture art speaks across time and space, then perhaps we can take time to reflect on hot-takes and their dangers and spend 2018 preparing to be more thoughtful and reflective in solving our problems.

[1] http://news.gallup.com/poll/195542/americans-trust-mass-media-sinks-new-low.aspx

David Feltmate is Associate Professor of Sociology at Auburn University at Montgomery. He received his PhD in Religious Studies from the University of Waterloo in 2011. His research areas include the Sociology of Religion, Religion and Popular Culture, Humor Studies, Social Theory, New Religious Movements, and Religion and Family. His book, Drawn to the Gods: Religion and Humor in The Simpsons, South Park, and Family Guy is available from New York University Press.