Louis A. Ruprecht Jr.

We have been here before.

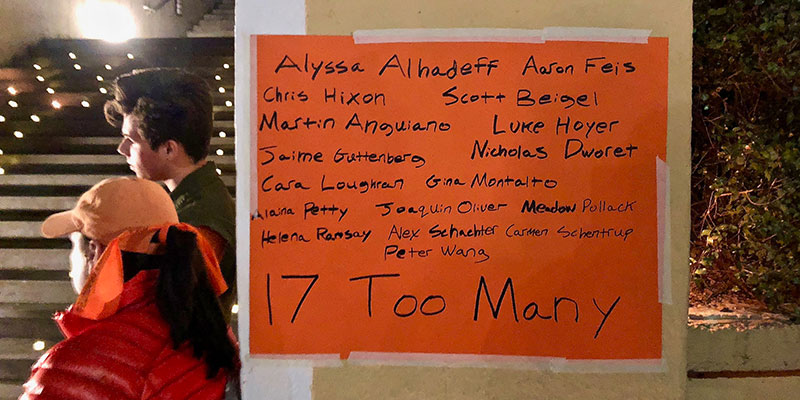

A troubled young adult storms a school with an arsenal of high capacity automatic weapons (the prefix, semi-, is practically meaningless in such a situation), acting for all the world as if he were storming an enemy’s fortified position. (Why schools are targets for such astonishing levels of violence and armament is a question for cultural anthropologists to which I will return). In a stunningly short period of time, seventeen people are dead and fourteen more are wounded. As first responders, police and others attempt to assert control over the carnage, and as faith communities turn to the agonizing task of commemorating and burying their dead, we try to comprehend what has happened and why it has happened.

We have been here before. But then, quite suddenly, something new.

What has not happened before is that a grass roots youth movement has been prompted by the catastrophe. Concluding that the adults in politics are effectively AWOL, they have taken the responsibility of initiating a rather different kind of public discussion, one that permits a place for the understandable outrage of victims to be expressed. In addition to the cries of outrage and the reasoned expressions of furious dismay, we also catch glimpses of the first stirrings of something else, a new way to talk and think about this complex topic of guns in America.

As an adult, and a teacher who wishes to support this youth movement, I offer here what they have helped me to see more clearly.

There is a simple distinction that might help us understand what they are trying to say, namely, the distinction between the gun industry (Remington Arms, Sturm Ruger, Beretta, Smith & Wesson, Colt, to name a few) and individual gun owners. All of our discussion about the meaning and limits of regulating gun ownership has focused exclusively on the gun owners–on the difficult question of who can own what, and when. But we have said very little about the interests of a multi-billion dollar industry whose only economic interest can be the continuous production and sale of more guns and more ammunition.

That’s obvious; that’s their business.

The NRA is a lobby which represents the interests of the gun industry, yet presents itself as if it were a lobby representing the interests of individual gun owners. These two interests do not align. Almost every discussion of gun control begins with the assumption that “bad people will get guns,” and what the most responsible thing to do in the face of such a truism might be. Like most truisms, it is not very true. It is a truism only so long as we refuse to move past the troubled young man with these guns, and turn to the other end of the economic equation: to the producers rather than the consumers, to the production and distribution rather than the purchase.

Turn off the spigot and there will in fact be fewer bad guys with guns.

This is a point so obvious that a child can see it. It is our children who are saying it now. A youthful killer has launched a grass roots youth movement among his surviving classmates. They are the ones who see the connection between Big Guns and Big Tobacco.

Before we engage in the necessary parsing of the question of what a gun is, we should ask ourselves what constitutes a youth in this country. At 16, a youth may grant sexual consent in most states of the union. At anywhere between 15 and 17 they may receive an operating permit, then a license, to drive a car. At 18 they may vote in local, state and national elections. At 21, they may drink a beer.

Looking at our culture as an anthropologist might, we would do well to ask what implicit social norms are expressed by a confusing legal regime like this. What kind of youth does our society imagine with such laws and their attendant social rituals?

They are post-pubescent, and potentially sexually active.

They are (auto)mobile, if they have the money.

They are inalienably eligible to vote, regardless of income level.

They may even enjoy an “adult beverage,” when the law decides they are

adult enough.

At what point in their development they may own a gun is a question we are currently debating. But again, we are looking at the wrong end of the equation, and thus at the wrong end of the gun. There is no age at which they may not be shot and killed. That is what they are telling us right now, virtually begging us to see and hear it.

This is not an easy space for youth to inhabit, culturally speaking: adult one moment, infantilized the next. Our youth are subject to a somewhat bewildering legal regime which sends very mixed signals about their level of maturity and their ability to make autonomous and responsible decisions. And what these vulnerable and culturally ambiguous youth are asking is whether the right to gun ownership is more analogous to the right to sexual expression, the right to drive a car, the right to have a beer, or the right to vote. It is an excellent question, and one that helps bring another conceptual approach to the question of guns into clarity.

One of the survivors of the shooting spree at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, a British citizen whose parents relocated to Florida for work, made an interesting observation on the PBS Newshour as he attempted to grapple with what had happened at his school and what may be done about it. In stark contrast to England where firearms are rarely seen in public, he observed, “I recognize that America is a gun culture.” With all due respect to his deep insight and to the trauma of his experience, I would suggest that he is wrong about that.

By any metric–historically, culturally or economically–America is a car culture; it has been one ever since Henry Ford invented the thing and promptly made a fortune. The youth are telling us that the right to use or own a gun is like the right to use or own a car.

The automobile industry is a powerful lobbying presence in the United States, with profits far larger than the gun industry’s, and we might presume that it carries more legislative weight as a result, but they started acting like grown-ups.

They do not cry foul at each and every suggestion that their products should be regulated. They happily submit to a regulatory regime that may be justified in terms of social safety and security, indeed, they go even further. They regularly self-regulate, issuing recalls of any instrument they have produced that might present a danger to individual car owners and everyone else on the road.

It is the NRA that consistently acts like a spoiled child. Much like Big Tobacco… until it didn’t.

Naturally, the first thing the NRA and other industry interests argue is that car ownership is not protected by the US Constitution (since they didn’t exist in 1791) but that gun ownership is. They are right about that. So let’s dig a little more deeply into the matter.

What is a car? It is a remarkable modern technological innovation designed to assist and enable the transport of human beings and their cargo. As the technology has changed (think of how far we have come from the Model T), cars have also come to serve other social purposes. They are used in sports, like NASCAR. They are even collected.

What is a gun? It is a remarkable modern technological innovation designed to kill human beings in war and animals in hunt. As the technology has changed (think of how far we have come from the front-loading musket with which the Framers fought our Revolution), guns have also come to serve other social purposes. They are used in sport, like the Olympics. They are even collected.

So far, so good. Now let us compare how we regulate these two eminently modern technologies.