By S. Brent Plate

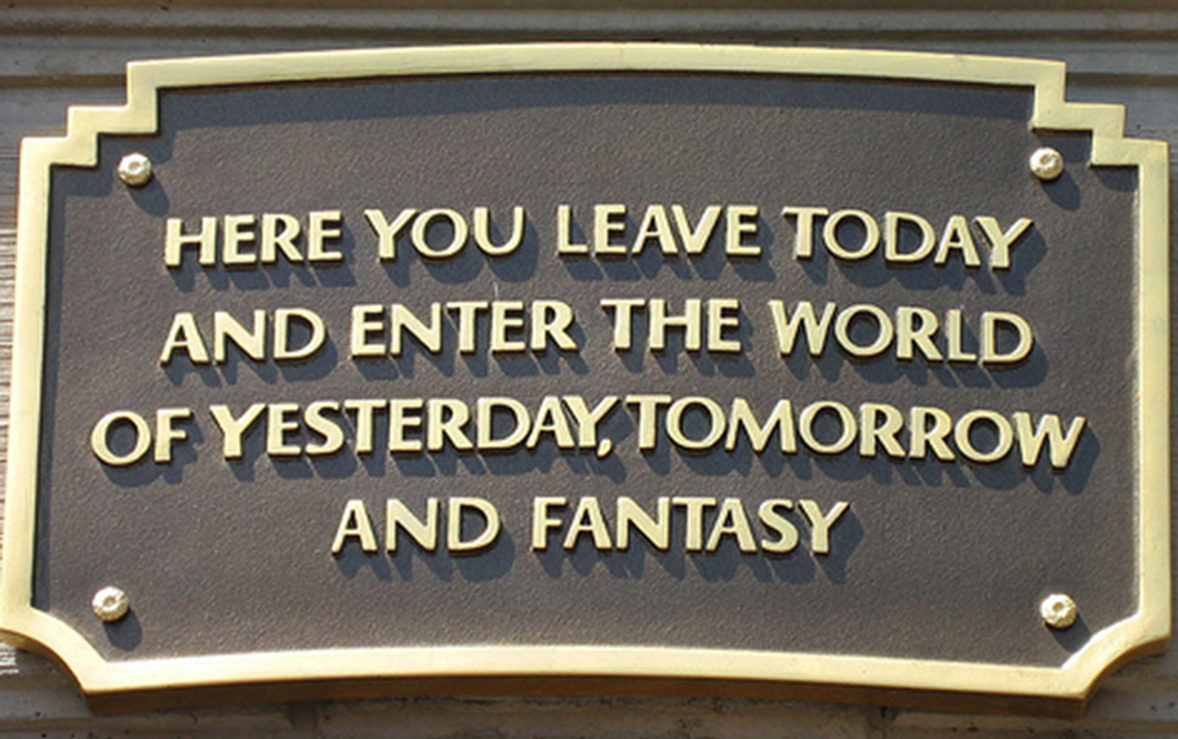

This is the sign that hangs over the entrance to Disneyland, less than an hour from where I grew up in Southern California. I realize some people save up for years to drive the kids in the family truckster to Orlando or Anaheim to see such a place, but I got to go there all the time. Friends and friends of friends always seemed to have passes and we’d go to explore, as well as create a little mischief, even if for just a few hours in an evening. Today, I could draw a quite precise map of the amusement park, telling you where to catch certain rides, where to eat a decent lunch, even where Snow White and the dwarves have their lunch. Years later I watch Frozen and Brave with my daughters, Saving Mr. Banks with my companion, and I still delight in the worlds of yesterday, tomorrow, and fantasy.

And I wonder now if maybe it’s this sign, this portent over the portal, that got me interested in the study of religion.

Elsewhere, I have argued that watching a film is akin to engaging with a religious practice: both entail that we leave the world of today and enter another world, a world where many of the rules of time and space have been changed. Like Morpheus says to Neo in the sparring program in The Matrix: “In this other world there are rules—some rules can be bent, and others can be broken.” These rules may be rules of gravity, rules of cause and effect, or rules of ethical behavior. The other worlds created through religion and the movies may be worlds we wish to live in (thus they are often, somewhat problematically, thought of as an “escape” from the rules of today), or they may be worlds we wish to avoid as much as possible (in which case they serve “prophetic” functions and warn us to change our ways).

Most importantly, the world of today and those other worlds are not kept separate, but continually toggle back and forth. We live fluidly across worlds.

In the pivotal conversion scene toward the end of Saving Mr. Banks, Walt Disney (Tom Hanks) sits with P.L. Travers (Emma Thompson) and explains, “This is what we storytellers do. We restore order with imagination. We instill hope again, and again, and again.” That other world of the story re-creates the here and now, makes the “world of today” different through adventure and fantasy.

Part of what it means to study religion is to scrutinize its constructed nature, examining the seams of the stories, in order to figure out how it was put together, and what impact it has on and through the communities of people who are part of its edifice. To do that in a thoughtful, and I would say responsible, way is not to aim to bring these worlds crashing down, but to have some of the fairy dust brush off on us. It is to enter adventureland, tomorrowland, and fantasyland and figure out what great heroes have journeyed through the land, what tomorrow looks like, and what makes those fantasies fly.

I can think of few better phrases for understanding religion, and the study thereof, than the term Walt Disney himself popularized: “Imagineering.” With this portmanteau, Disney named the process of creating the theme parks and related entertainment venues (cruise ships, resorts, real estate, etc.). Disney’s Imagineering Field Guide to Disneyland suggests that the amusement park “is essentially a movie that allows you to walk right in and join in the fun.” Further, the Disney parks “have become the physical embodiment of all that our company’s mythologies represent to kids of all ages.”

With such language we might conjecture how religious worlds too are imagineered. They are not simply “constructed,” but are born out of imagination and engineering. They require aesthetic know-how.

We academics can sometimes be cynical enough to throw a rock in the air to hit someone guilty, and Disney becomes an immense barn door on to which we hurl our gestures of criticism. Rightly so in many cases. Summing up many of the critiques over the decades, Eleanor Byrne and Martin McQuillan note in Deconstructing Disney: “Disney has become synonymous with a certain conservative, patriarchal, heterosexual ideology which is loosely associated with American culture imperialism.”

As someone who studies visual culture, I’m convinced that, among other things, media images and personal body images are intricately enmeshed. Too much exposure to chalk-white, hourglass-shaped princesses are probably not good for my daughters for their sense of self and identity. But too little parental contact and discussion in relation to media images (too little parental imagineering) is also not good for them; parenting skills are not far from academic skills. Imagineering is a powerful force that, like that other cinematic “force,” can be used for good or ill.

So while religious traditions are imagineered, religious studies also needs to employ imagineering to imaginatively approach the engineered structures. This approach requires an in-depth exploration of aesthetics in its deep connections with sense perception, the constructions of the ways we see and hear and taste and feel and the ways these senses are tricked and delighted, toyed with and influenced.

We can search for religion in popular culture or, better, popular culture can provide great analogies to religious traditions (this is like that). But pop culture also carries with it methods for the analysis of religion: understanding religion through the production of pop culture. Imagineering may prove to be a critically sensitive approach to the study of religion and its worlds, however plastered, pilfered, and pretend that they are.

S. Brent Plate is a visiting associate professor of Religious Studies at Hamilton College. His most recent book is A History of Religion in 5 1/2 Objects: Bringing the Spiritual to Its Senses. He is also co-founder and managing editor of the journal Material Religion: The Journal of Objects, Art, and Belief and a contributor to The Huffington Post and Religious Dispatches.