S. Brent Plate

A strange set of coincidences brought Malcolm X into my life in the past couple months, some invisible force of history that compelled a fusion of events. It was only at the start of this year that I realized February 21 was the 50th anniversary of his assassination, but energies were in play long before then that brought me to encounter Malcolm’s powerful ghosts. They arrived in buildings, books, bodies, and films.

A day before the anniversary, I had a dinner engagement in Harlem, a few blocks down the road from where the Audubon Ballroom used to be, now a gentrified area in Washington Heights at the edge of New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center. When Columbia was expanding in the 1980s, the school planned to tear down the Audubon. Protests not only saved it from demolition but generated energy and money for restoration. By the 1990s the building had been fully renovated and today includes the Malcolm X and Dr. Betty Shabazz Memorial and Educational Center along with Chase bank, Dallas BBQ, and Caffe X. As I passed by the building, I thought about its presence there for the past one hundred years and witness to histories of economic and social crescendo and diminuendo. A life-sized statue of Malcolm X stands in the Shabazz Center today, though his ghosts are much larger than life.

The ghosts also visited my class this semester, “Religious Diversity in the United States,” two hundred miles northwest of the Audubon Ballroom. I had been teaching a similar course for several years as an upper-level seminar, but wanted to adapt it for first year students, to get something more foundational into their liberal arts diet. And rather than show a lot of statistics about diversity, I thought I’d begin with some personal stories.

We started the semester with a series of autobiographies of people growing up religious in the United States who encountered “diversity” in some form, and made the further step of learning about lives and practices other than their own. The narrative arc I was hoping to teach about was a set of stories that ultimately leaned toward pluralism. For various reasons I won’t fully describe here, I ended up with an assortment of texts that offered some montage of religious experiences.

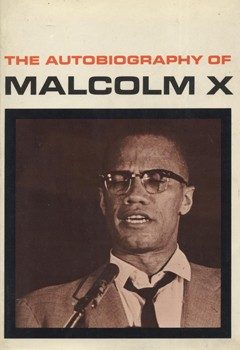

The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Diana Eck’s Encountering God are two stories of Christians from the United States who were challenged and inspired by practices and philosophies found in India. Eboo Patel’s Acts of Faith and The Autobiography of Malcolm X both discuss engagements with various forms of Islam. Part of the impulse is to show the diversity within traditions; there is no singular “Islam” or “Christianity,” only “Islams” and “Christianities.” (It is worth noting that Word program I am using has these two plural nouns underlined in red, meaning the software does not recognize plural forms of religious traditions; i.e., the norm is that Christianity is singular.)

By coincidence we finished up our section on Malcolm X on February 18, three days before the anniversary of his death. The week previous I had invited a local retired African-American Imam into my class. Sabur Abdul-Salaam, who grew up in Philadelphia and New York City in the 1950s and 60s, saw his older brother die at 25 and found ways of dealing with problems of race unique to northern cities at the time. Malcolm’s Autobiography was instrumental to him at this time, as Sabur saw a life parallel, in some ways, to his own. When he hit his own crisis point, it was to the Quran he turned, and has now spent many years as a Muslim chaplain to the local prison system. Today, in his late sixties, Sabur is testimony to the restorative power of Islam, and to the living ghosts of Malcolm.

Ultimately, my class turned to Spike Lee’s magnificent Malcolm X (1992), starring the dazzling Denzel Washington—who should have been nominated for an Oscar for this. When we see the continued whitewashing of the Academy, we know it’s been going on for a very long time. Lee’s Malcolm X adds as much to the life as it takes away. Particularly interesting with the film is the way it plays with the layers of storytelling, self-reflexively noting its fictional qualities. Lee’s film is “based on” the Autobiography of Malcolm X which is in turn, “told to Alex Haley.” Lee, at first, seems to be a few steps removed.

Yet, our myths and our histories are constantly intertwined. There is no way out of this intermixing. Spike Lee gets this. He mixes layers of history and story, from the anachronistic opening sequence of George Holliday’s footage of Rodney King being beaten by Los Angeles policemen in 1991, juxtaposed with a burning American flag, to Malcolm’s film camera brought with him on the Hajj where we see Denzel-as-Malcolm-with-a-camera, and levels of filming are interposed. A number of scenes of the film are fairly direct remakes of iconic images and speeches recorded in various media. The scenes in Mecca were taken by a small team from Lee’s production crew, apparently the first 35mm-feature film crew ever to be allowed to shoot in the holy city.

Just after the assassination occurs in the film, all footage from that point on is from “actual” films and photos. The film shifts from acting to actual, seeing the flesh and blood Malcolm in black-and-white newsreels. Ultimately, the actual footage shifts to contemporary events in Soweto, South Africa, then, to street signs from Harlem showing Lenox Ave as Malcolm X Blvd and ultimately into a South African classroom with Nelson Mandela. We are left with a series of actual and acted events that coalesce to form a lasting impression, much in the way our brain synthesizes varieties of images and stories to form our memories. The story has been embodied, the ghost has found a medium in the form of the film.

Coda: Around 1910, the Hungarian immigrant William Fox began buying, leasing, and building a number of theaters in the United States, seeing the coming of the movies as a worthwhile investment. In 1915 he founded the Fox Film Company, and the story is now history. One of the spaces that Fox had built in 1912 was the Audubon Ballroom, in which were shown vaudeville plays and movies.

S. Brent Plate is a visiting associate professor of Religious Studies at Hamilton College. His most recent book is A History of Religion in 5 1/2 Objects: Bringing the Spiritual to Its Senses. He is also co-founder and managing editor of the journal Material Religion: The Journal of Objects, Art, and Belief and a contributor to The Huffington Post and Religious Dispatches. He can be followed @splate1.