By Louis A. Ruprecht Jr.

For anyone who is interested in religion and the arts, Susan Sontag’s (1933-2004) work remains essential. She burst upon the New York arts scene in 1966 with the publication of her collection of essays, Against Interpretation. The book was a tour de force examination of everything from second rate horror films to Critical Theory. Her primary interests were the performative arts, photography and film.

In subsequent publications, we were to learn of her specific interest (and concern) with the power of modern technology to create new ways of seeing. This led to what was perhaps her most famous single essay of the time, the condemnation of the Nazis’ most famous documentary filmmaker, Leni Riefenstahl.

“Fascinating Fascism” was published in 1975 in the collection, Under the Sign of Saturn. Refusing the program of self-rehabilitation that Riefenstahl had enacted with the 1974 publication of her luscious photographs of the Nuba people, Sontag argued that there was in fact such a thing as a “fascist aesthetics,” and that these photographs were as unapologetically fascist as Riefenstahl’s notorious documentaries, Triumph of the Will and Olympiad. Once a fascist, always a fascist, Sontag warned, unless there are clear words of retraction and apology. Riefenstahl refused to apologize for anything; Sontag saw this as unacceptably irresponsible for an artist of her talent and stature.

How, one wonders, could Sontag muster up this level of animosity for a woman she had never met? In short, because Sontag believed that photography and film were matters of life and death… literally. In her 1977 book, On Photography, Sontag attempted to show how omnipresent photographic images have become for modern people, and she attempted to trace out “the meaning and career” of photographs. Photography, she suggested, has always had an unsettling relationship with sexual voyeurism and with death. This is doubly strange, Sontag observes, since photography was supposed to have something fundamentally to do with beauty. In 1841, Fox Talbot called the photograph a “calotype” when he applied for a US patent, deriving the term from the Greek word for beauty, kalos.

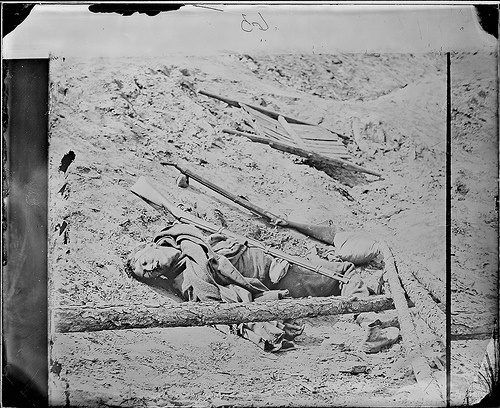

We can see why Sontag might worry. Photography unfolded within a complex cultural history in which not just sex, but death itself was made beautiful. The necrophilia of Matthew Brady’s Civil War photographs is a case in point. Sontag also worried that photographs were too easily and too quickly taken, their very speed creating “a very tenuous relation to knowing.” Time is money in American culture, she warned, not an idea conducive to enhancing critical thought.

Sontag returned to that set of problems in her last book, Regarding the Pain of Others, in 2002. War photography, death photography, the photography of atrocities at Auschwitz and Srebrenica and elsewhere… all of these things, she worried, were contributing to a vast public desensitization in the face of pain. Depicted pain is not real pain: the films of Quentin Tarantino make sense only in such a world.

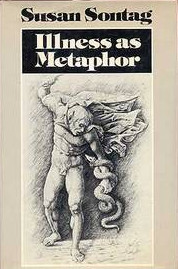

In 1978, Sontag was interviewed by Jonathan Cott for Rolling Stone Magazine. The two met twice, first in Paris and then six months later in New York. Less than a third of their conversation was published by the magazine in October 1979. The entirety of their discussion, Susan Sontag: The Complete Rolling Stone Interview, was published last year by Yale University Press. Not long before their meeting, Sontag was diagnosed with cancer and, because she was Susan Sontag, she wrote about that, too. Illness as Metaphor was published in 1978, and in it, she offered a brilliant comparison between the way tuberculosis — “consumption” — was described in the nineteenth century and the way cancer was described in the twentieth. Both illnesses, precisely because they were so consuming, were also moralized. “If only he hadn’t been a Romantic poet, he wouldn’t have burned out so quickly…If only I’d lived with less stress, I wouldn’t have made myself sick.”

Cott invited Sontag to talk about this, with a quotation from the Goncourt brothers: “Sickness sensitizes man for observation, like a photographic plate” (15). Sontag saw the connection between her work on Photography and Illness. But now she added a new category and concern: transcendence, spirituality and the sacred. She observes:

Everything in this society–in the way we live–conspires to eliminate anything other than the most banal of feelings. There’s no sense of the sacred or of some other state of transcendence that people have always talked about since the beginning of thought. There’s been a collapse of religious vocabularies that once described that other state. (15)

Sontag suggested that the dichotomy of illness and wellness had taken the place of sacred and profane, and that while “there is a truth in the romanticization of illness” (16), its effect was anything but benign. Just as the human body has a capacity for recovery, so the human spirit has a capacity for the sacred, she believed.

There’s not only a human need for transcendence, there’s a human capacity for transcendence and for more profound states of feeling and for greater sensitivity, and this has always been described in religious terms in one way or another. All of those religious vocabularies collapsed, and in their place we now have our medical and psychiatric vocabularies. (16)

I don’t think Sontag was arguing against secular science or the importance of secular politics here; she was much too pluralist for that. No, her subtle sense of religiosity’s porosity and essential fluidity inclined her to see spiritual energies going elsewhere, not going away. “The two things that spiritual values have become attached to since the collapse of religious faith are art and illness” (17), she observed. I will have more to say about religion’s going elsewhere, and especially about how spiritual value has been translated into our modern conception of art in my next essay.

Louis A. Ruprecht Jr. is the William Suttles Chair in Religious Studies and an affiliate faculty member with the Hellenic Studies Center and the Center for Collaborative Scholarship in the Humanities at Georgia State University. His latest book is Winckelmann and the Vatican’s First Profane Museum, (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011).