Jolyon Baraka Thomas

We are pretty familiar with how Tokyo’s neighborhoods reward the adventurous, so when Three and I met up for drinks in Nakano on an autumn evening in 2012, we struck out for one of the small side streets near the station instead of walking down the larger shopping arcade directly across from the station exit. We immediately found ourselves in a maze of narrow lanes barely big enough to accommodate foot traffic, let alone vehicles. Japanese tapas bars (izakaya) and noodle shops cozied up to establishments catering to the prurient interests of a heterosexual male clientele. Young women on advertising posters coquettishly eyed passersby while well-dressed hustlers inveigled groups of suited salarymen to step inside.

Japan’s relatively liberal sexual mores have been a source of fascination and consternation for generations of foreign visitors, but the expat in Tokyo quickly adjusts to the fact that seedy establishments that target patrons’ concupiscence often sit side-by-side with ordinary restaurants, bars, and cafés. Euphemistically known as “custom” (fūzoku), Japan’s sex industry includes many barely legal establishments that offer various opportunities for men to flirt and cuddle with nubile young women. Technically, fūzoku do not allow penetrative sexual intercourse, but in practice the line between titillation and prostitution is somewhat blurry: “pink salons” offer fellatio services to patrons, for example, and “soaplands” offer a sudsy full-body massage.

While people around us may have been in Nakano looking for love, our interests were relatively pedestrian. We walked deeper into the warren of restaurants and bars in search of a drink and a meal. We passed an Irish pub, a darts bar, and an establishment that offered a special “course” in which a young woman sporting a maid’s outfit would sit on a patron’s lap and clean his ears.

If Japan is a place where American sexual prudery easily rears its head, it is also where America’s racist kitsch goes to die. Our first stop for an aperitif was in a second-story bar that seemed decent, but it was certainly not decent enough to have a second beer under the watchful grin of the creepy minstrel statue standing in the corner. We descended back to the street and walked two or three short blocks before stopping for a delicious meal of yakitori (grilled chicken on a skewer) and oden (assorted stewed morsels) at a dingy little stall, sitting on worn stools under an awning outside while a pleasant autumn drizzle rendered the neon signs around us soft and warm.

Over years of living off and on as expats in Tokyo, Three and I have become master flâneurs. Our outings tend to involve a combination of aimless wandering, visiting a series of establishments, drinking beers on the street (delightfully legal in Japan, if not exactly considered classy), and getting hopelessly lost.

Years ago we invented a game to aid in these peripatetic outings. Every time we reached an intersection in Tokyo’s labyrinthine mass of streets and alleys, each of us would pick a direction at random. We would then decide on our next move by playing rock-paper-scissors (jan-ken-pon). The only rule was that we absolutely could not travel back in the direction from which we had come. Needless to say, “leaving things up to the jan-ken gods,” as we came to call it, became a fantastic way of getting to know the city and has led to some memorable urban adventures. It is always when we are in the middle of the most random neighborhood that we find the coolest little bar or cafe—just around a corner, or up an unmarked flight of stairs.

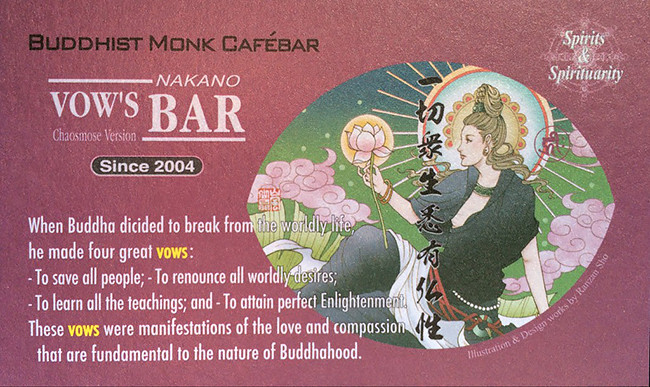

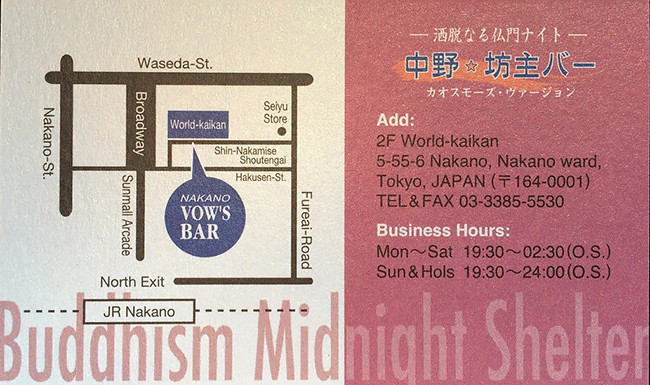

This evening was no different, although in retrospect I can’t remember if it was the jan-ken gods or some uncanny sixth sense that guided us. However it happened, when we finished our meal we headed deeper into the warren of narrow streets and found ourselves in front of a nondescript edifice filled with the small drinking establishments known as “snack bars.” I recognized the name of one—Vow’s Bar. (The name is written bōzu bā, a play on words pairing a common term for a Buddhist priest with the Japanese transliteration of the English word “bar”.) The small chain offers patrons a chance to nurse original cocktails with names like “Form is Emptiness” (shiki soku ze kū) and “Pure Land Paradise” (gokuraku jōdo) while listening to dharma talks delivered by Buddhist priests. Since Three and I were both in Tokyo on research fellowships so that we could study Japanese Buddhism, our next stop for the evening was obvious.

When we stepped inside, the priest-bartender was standing behind the bar amiably chatting with two patrons who appeared to be on a date. Visually, Three and I are sort of like a nerdy academic version of the salt-and-pepper cop duos who featured in an earlier generation of action cinema, so we’re pretty used to eliciting surprised reactions from proprietors in relatively homogenous Japan. The bartender in this case, however, smoothly welcomed us to two of the four available barstools, asking us what we did for a living as we looked over the menu.

The question is always a tricky one in Japan. If I respond candidly that I study Japanese religion, my interlocutor will often indicate discomfort or will quickly ask a clarifying question to make sure that I am not out to proselytize. This sort of wary response is typical in a country where very few people describe themselves as “religious” and in which—especially after the 1995 sarin gas attacks perpetrated by the religious group Aum Shinrikyō—“religion” is frequently understood in negative terms.

I could have anticipated that a Buddhist priest managing a bar would have a more positive reaction to the news that we studied Buddhism. What I did not anticipate was that our academic interests and our affiliations with two of Japan’s most respected universities would suddenly become woven into the dharma talk already in progress. “You see?” the priest said to the dating couple. “Even foreign researchers are studying Japanese Buddhism!” He began pumping us for more information.

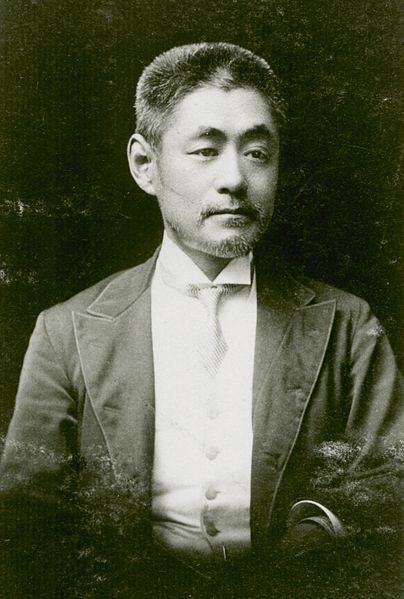

When I responded in the affirmative to the priest’s follow-up question about whether I was familiar with the famed Buddhist reformer Inoue Enryō (1858–1919), his pleasure was evident. He left us to our drinks, but he continued his dharma talk by smoothly launching into a short lecture for the couple on how many Buddhists were now studying Inoue Enryō’s work for clues as to how Buddhism might adapt to Japan’s rapidly shifting social climate.

I couldn’t help but listen in. It seemed strange to me that the bartender would be celebrating Inoue’s ideas from the turn of the twentieth century for their applicability to the very different circumstances of the present, but I also wondered if he would have anything to say about Inoue’s pet distinctions between “real religion” and “superstition.”

It turned out that I did not have to wait long. Three and I sipped our drinks and quietly murmured to each other in English about how deftly the affable proprietor had used our arrival to launch into a spiel about Buddhism’s importance for daily life in contemporary Japan. He was obviously skilled at his craft, and we each kept an ear cocked to listen to him as he hit his stride. And then it came.

Keeping his body positioned so that it was clear that he was still talking to the couple, the bartender turned to us to ask if in our studies we had encountered any of the so-called new religions that have emerged in Japan in the last century or so.

“Of course!” we replied.

“Ah, but have you seen their videos?”

Suddenly, the mountain of DVDs and VHS tapes sitting under the large television screen at one end of the room made sense. Shuffling through some media, the barkeep bonze put on a video of GLA (an acronym for God Light Association), a religion known for its practice of glossolalia (more here behind a paywall). As people on the video began speaking in tongues, the priest offered a running commentary.

It basically went like this: In contrast to such a strange practice advocated by an obviously strange religion, Buddhism alone is precisely the sort of tradition appropriate for the contemporary age. After all, Buddhism boasts a rare and delicate blend of respect for tradition and a progressive mentality, while groups like GLA advocate strange “superstitious” practices. You get the idea.

![Screenshot from Eien no hō [The Eternal Laws] by Jolyon B. Thomas](https://sacredmattersmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/shot.jpg)

Three and I have both spent some time with Happy Science promotional materials as part of our professional study of Japanese religions, so we were not particularly surprised by the video’s ornate settings, baroque soundtrack, and tearful taikendan (experiential accounts) in which Happy Science members recounted the power of Ōkawa’s teachings. For the bartender’s intended audience, however, this was a prime opportunity for him to reinforce his message about the “real religion” of Buddhism versus the “false religion” presented by Happy Science. His sermon proceeded in a way that left both of us pretty uncomfortable, but seemed to have the dating couple more or less convinced.

The bartender ultimately gave up on us as allies in his dharma talk, but as I finished my drink I couldn’t help but marvel at the web of competing understandings of authority and authenticity that crisscrossed the bar during our brief encounter. As an informal space set aside for laypeople to encounter Buddhism, Vow’s serves as a place for priests to gently administer the medicine of the dharma through the expedient means (hōben) of cocktails and chitchat. But it also serves as a place to hierarchically order religions, ranking and ordering specific traditions as beneficial, benign, or deleterious. With our arrival, these dynamics were complicated by yet another set of distinctions that inevitably crop up when “in the field”: foreign versus Japanese understandings of local traditions; academic versus confessional understandings of Buddhism.

I have no way of knowing how the dating couple actually received the bartender’s sermon. However they interpreted his message, in the cozy space of Vow’s the bartender clearly had the last word about what information was privileged and what was not. For all the loquaciousness of their promotional videos, the new religions he discussed could be rendered mute with the click of a button and a dismissive turn of phrase. Similarly, Three and I were paying customers who gamely contributed to the genial conversation at the bar, but ultimately we were merely a prop in the barkeep’s rhetorical toolkit. Our training was valued not because we had specific expertise that could push the conversation in new directions, but rather for the legitimacy it could lend to Buddhism. When we shied away from making value judgments about the videos, we ceased to be useful for the task at hand.

The bartender may have controlled the narrative in that space and at that particular moment, but when I retrospectively describe the moment in an ethnographic mode (as I have done here), I subvert the hierarchy he so carefully constructed. I write and speak in a re-descriptive mode rather than a confessional one. I resist the stark distinctions that he wanted to draw between authentic and ersatz religion. And I regard prominent figures in Buddhist intellectual history such as Inoue Enryō as flawed ideologues rather than infallibly prescient saints.

My training and the force of scholarly habit make me leery of apologetic projects that seek to hierarchically arrange religions, but they also make me suspicious of a reactionary tendency to view the very existence of a Buddhist bar as a contradiction in terms. Many laypeople see it as an abrogation of the basic precepts to imbibe intoxicants, let alone to run a commercial business that serves alcoholic drinks. This sort of view is premised on the problematic assumption that “good” religious people should be neither epicurean nor acquisitive. But if it is technically a violation of the Buddhist precepts for clerics to consume intoxicants and handle cash, centuries of doctrinal interpretation and the weight of historical precedent suggest that Japanese Buddhist priests are fully justified in using a spoonful of alcoholic sugar to help the medicine of the dharma go down.

One question keeps nagging at my conscience since my visit to Vow’s, however. It concerns whether there might be some way to understand and describe religious authenticity that is not captive to the pet presuppositions of clerics, laypeople, or scholars. Laypeople often presume to know Buddhist doctrine better than clerics themselves do, and will frequently police clerics for potential infractions. Clerics often appropriate academic expertise and scholarly rhetoric in the service of making apologetic claims. Meanwhile, academics sometimes see clerics and laypeople alike as lacking basic factual understanding of their own traditions. Given this state of affairs, how can any of these groups possibly describe Buddhism in a way that is persuasive, sensible, and aware of the competing visions of authenticity and authority held by the other parties?

It was the jan-ken gods that got me into this intellectual quandary by leading me to Vow’s in the first place. Perhaps I should appeal to them for an answer.

Jolyon Baraka Thomas is an A.W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in the Center for the Humanities at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he teaches courses in (or cross-listed between) Religious Studies, East Asian Studies, and History. His research covers topics such as the politics of religious freedom, religion and media, and relationships between religion, sex, and gender. Jolyon is also Editor of Asian Traditions at the Marginalia Review of Books. He can be followed @jolyonbt.