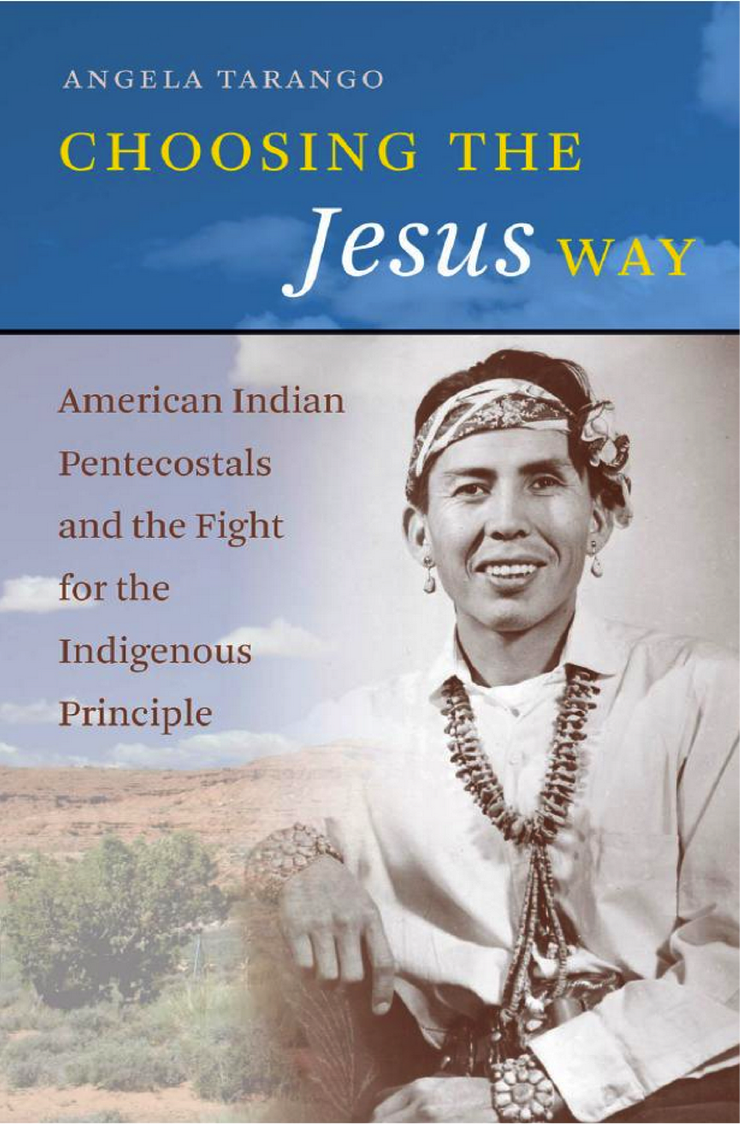

In our new interview series, we ask cultural theorists about what inspires them and how their latest work challenges our understanding of the sacred in American cultural life. For this segment, we chatted with Angela Tarango about her latest book, Choosing the Jesus Way: American Indian Pentecostals and the Fight for the Indigenous Principle.

1. What sparked the idea for writing this book? Why write it now?

In the last decade or so, scholars of religion have been paying a lot of attention to Pentecostalism, especially global Pentecostalism. When I discovered that there was a long and fascinating history of Pentecostalism among Native Americans, I was surprised that no one had written about it and that few outside of the faith actually knew that Pentecostal Native Americans existed. Traditionally, Pentecostalism had been seen as a faith that started among African Americans and whites. In the last decade, we have seen Latino scholars such as Arlene Sanchez-Walsh, Dan Ramirez, and Gaston Espinoza fight hard to include Latinos in the Pentecostal narrative, yet no one had done the same for Native Americans. So I decided it was time. I wanted the voices of the first generation of Native Pentecostal believers to be heard.

2. How would you define “religion” in relation to your work? Where do you see the sacred or sacred things in this book?

I make the argument that for Native Pentecostals, the indigenous principle itself becomes a form of religious practice—that in fighting for the principle it became a lived theology that came to embody the struggle of the Native Pentecostal community.

Otherwise, religion is fairly straightforwardly defined in this book—mainly as Pentecostal practice, belief, and theology. Yet, it is always important to remember when dealing with Native American religions that “religion” is a Western construct and especially once you get away from Natives who are Christians (and even in the case of Christian Natives), that using the term “religion” can be problematic. Mike McNally prefers “lifeways” which I find appealing, but you have to be flexible with the term when talking about Native Americans.

3. Can you summarize the three key points you’d like the reader to walk away with when finished?

- Native Americans took the indigenous principle, a colonizing missionary theology created by white Pentecostals, and re-shaped it to become truly indigenous (that is, to reflect their Native lives and faith within Pentecostalism) and used it as a tool to critique the Assemblies of God for its ethnocentrism and racism in how it treated Native believers.

- That Native Americans have been a part of Pentecostalism from its very beginnings as a movement. They were not always treated fairly by the Assemblies of God (AG), but they are very much a part of the history of the denomination.

- That Native Americans can and have embraced forms of Christianity in the twentieth and twenty-first century and turned it from a religion of their colonizers into something that uniquely reflects their experiences as Christians and Native Americans.

4. Who are your inspirations or intellectual models for you as you wrote this book?

I really loved Mike McNally’s work on Ojibwe hymn singing and its multilayered meanings and early on in my career his work inspired me to work in Native American religions. I found writing inspiration in the late anthropologist Keith Basso’s writings—his book Wisdom Sits in Places is an extraordinary little work on the importance of place, space, and collective memory among the Western Apache, and it is so well written. As a book it is poetic and beautiful, it makes you laugh in spots, and wish you could be out in the trail with him and his Apache informants. Finally, my PhD advisor, Grant Wacker, inspired me in his work on Pentecostalism and to always write in a direct, clear, and straightforward voice. “Like as if you were writing it for your grandma to read it.” I can still hear him saying that.

5. What was the most difficult thing about writing the book? Did you encounter any unexpected problems or challenges?

The biggest difficulty was a huge one: the scarcity of Native voices in the sources. Almost no early AG Native leaders left behind memoirs, most were dead by the time I started working on this project, and what little I could find was patchy and incomplete. I ended up building the history mainly out of periodical sources (The Pentecostal Evangel) and then worked from those to track down what information I could. This is the reason why the book is so strongly driven by narrative, and it focuses on a few key leaders because they were the only ones I could consistently trace over the decades in Pentecostal periodicals.

6. What’s the most unexpected response, critical or positive, that you’ve gotten about the book?

I’ve had a couple of Native Pentecostals—young people, often future church leaders at Assembly of God seminaries and Bible schools, contact me and thank me for taking the time to tell the story of their forefathers. I love getting those emails because it reminds me that history is personal—it isn’t just for the academy, or so that we can establish ourselves as scholars, or get into intellectual arguments with each other. For some people, it’s a lot to simply be included, for history to bring in their voices, their stories, to validate them, and to give them their rightful place at the table.

7. With this book done, what’s up next for you?

This summer I’ve been working with a student and we have been looking at Native American casinos in Oklahoma, how they relate to sacred land, and what that means for them as emblems of political power and sovereignty. We visited twenty-three casinos across the state in nine days. It was pretty epic road trip. The results of it will become an article that will come out in a collected volume in a few years. That’s my small project. My bigger multi-year project is a history of religion and religious differences among the Navajo nation in the mid-twentieth century. I also go up for tenure this fall, which is a big moment in any scholar’s life.

Angela Tarango is an assistant professor of religion at Trinity University where she teaches Religion in America, especially minority traditions (African American, Latino, Native American). She received her PhD from Duke in 2009 and, when not researching Native American religious traditions, she enjoys road trips with her cat and dog, weaving, and exploring the great, confounding, exasperating state of Texas. In her own words, “They say everything is bigger here, and that is true for many things—especially the roaches. Those suckers fly.”