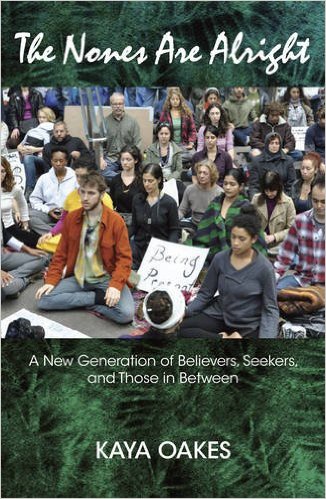

In our interview series, “Seven Questions,” we ask some very smart people about what inspires them and how their latest work enhances our understanding of the sacred in cultural life. For this segment, we solicited responses from Kaya Oakes, author of The Nones Are Alright (Orbis Books, 2016)

1) What sparked the idea for writing this book?

In 2013 I wrote a short essay for the Jesuit-run magazine America with the same title as the eventual book. I’d been thinking about the Pew studies that had traced the increasing number of “nones” since I happen to be married to one of them and a large percentage of my peer group, students and colleagues at UC Berkeley, would also fit into that category. Pew defines “nones” as those who check “none” or “no religion” on a survey, but my suspicion was that the term was failing to really define what was happening to American religion in a larger sense. The drift from organized religion didn’t necessarily mean people had no religion, but there was no category for “some,” “all”, “occasionally” or “many” or “it’s complicated.” So the article in America was a call to more dialogue about what “none” really means.

In 2013 I wrote a short essay for the Jesuit-run magazine America with the same title as the eventual book. I’d been thinking about the Pew studies that had traced the increasing number of “nones” since I happen to be married to one of them and a large percentage of my peer group, students and colleagues at UC Berkeley, would also fit into that category. Pew defines “nones” as those who check “none” or “no religion” on a survey, but my suspicion was that the term was failing to really define what was happening to American religion in a larger sense. The drift from organized religion didn’t necessarily mean people had no religion, but there was no category for “some,” “all”, “occasionally” or “many” or “it’s complicated.” So the article in America was a call to more dialogue about what “none” really means.

One of the other contributing writers to America is Jim Keane, who’s an editor at Orbis Books. Jim emailed and asked if I might be interested in developing the article into a book-length project. My memoir about Catholicism had been released in 2012, and I had the time and brain space to consider a new project, so his timing was perfect. I’d also long been an admirer of Orbis for being on the cutting edge of theology: liberation theology, feminist, womanist and Mujerista theology, and so on. Jim is also an excellent writer, which is something helpful in an editor since the process involves so much collaboration. So, after some wrangling with my agent (I’d only ever published with secular publishers before), a contract emerged and we were off to the races.

2) How would you define religion in relation to your work? Where do you see the sacred or sacred things in this book?

My feeling about “nones” is that they are actually quite similar to the DIY/indie communities I wrote about in Slanted and Enchanted. Seekers tend to curate or tailor religious and sacred experiences to what fits them best rather than assuming that one-size-fits-all formulas for the sacred are going to work. My own Catholicism is very DIY because I was not catechized in a traditional way, and many people in my generation had parents who were themselves drifting from traditional religious practice, as mine also did. Thus, much of our experience of the sacred takes non-traditional forms and involves drawing on multiple spiritual traditions at once. We also belong increasingly to decentralized communities scattered around the world, and rely more on the Internet to provide community as a result. And yet, there was a real sense throughout doing the interviews that comprise a lot of the book that this was deeply sacred work: holding people’s stories, amplifying them through writing, and engaging in dialogue post publication about this fragile thing we call faith.

3) Can you summarize the three key points you’d like the reader to walk away with when finished?

- Religion is not dying in America, but it is evolving beyond institutional walls.

- The “nones” are often more spiritual and more concerned with social justice then the religious are.

- Rather than judging or condemning the religiously unaffiliated, religious institutions would do well to actually listen to them.

4) Who were intellectual models or inspirations for you as you wrote this book?

The book evolved out of the interviews, so everyone I spoke to helped me think through the central question about where religion is going right now. I also considered similar sorts of oral history-based books, but not necessarily about religion. For example, Michael Azzerad’s book Our Band Could Be Your Life about the rise of punk and indie music showed how people made their own scenes when doors were constantly being shut to them. That felt more in kinship with the experiences of my interviewees than many academic books about religion did. That being said, I did draw on Patrick Cheng’s Radical Love to write about Queer experiences of religion, on Chris Stedman’s Faitheist to write about atheists and agnostics working in collaboration with believers and on Susan Katz-Miller’s On Being Both to write about interfaith families. Interestingly, I also thought a lot about Richard Rodriguez’s memoir Darling: A Spiritual Autobiography as I was writing this book. Richard and I did a public conversation on writing about religion in the fall of 2014, as I was just starting to go deep into writing this manuscript. What I love about his writing is that it’s a collage of history, conversations, his own thinking and deep images that stay with you when you’re done reading. And he resisted writing too much about his own experiences as a gay Chicano Catholic until he felt it was the right time to do so, so his faith is very intimate, very close to the bone. It’ll be a long, long time before I can write anywhere near as well as Richard does, but he is a role model for my work.

5) What was the most difficult thing about writing the book? Did you encounter any unexpected problems or challenges?

As with any book there were a lot of unexpected turns and challenges. In the last few years I’ve been traveling more than ever before to speak at schools and conferences, and that on top of a full-time job teaching on top of journalism work on top of the book work was a lot to take on. Unexpected challenges were mostly about time management: for example, one semester I went from a Tuesday/Thursday teaching schedule, when I could write on Fridays, to a Monday/Wednesday/Friday one, when I could write… almost never. I had a year to complete the manuscript including research, which is the same timeframe I’ve had for all of my nonfiction books. You have to hoard your writing time when life comes at you like that, and it was a struggle to do so on top of the interviews and research this book required. Sometimes I tell people the only reason I’ve managed to write four books with a full-time teaching job that doesn’t allow sabbaticals is because I don’t have children.

Another turn was figuring out what kind of book this would be. I knew scholarly was out of the question (see below), but what kind of tone? What kind of voice? Third person was fine for the interviews, but it also felt important to do some framing about my own experiences because I come from the same generation and background as many of my interviewees. I don’t want to write another memoir because my life just isn’t that compelling, but some personal details about my own religious experiences seemed important for the sake of positioning. In the end I wound up with a combination of first and third person, a point of view my creative nonfiction students at Berkeley once referred to as “thirst person.” We laugh a lot in class when things like that happen, by the way.

6) What’s the most unexpected response, critical or positive, that you’ve gotten about the book?

As this is my fourth book I’ve become accustomed to people’s critical responses. Most often, that takes the form of “this book should have been about X, Y, Z” rather than trying to engage what it is actually about. Some scholarly journals have found this book puzzling because they wanted it to be more of a scholarly book, but I’m not a religion scholar, don’t have a PhD, don’t go to the American Academy of Religion , don’t teach Religious Studies or Theology — Berkeley doesn’t even have a Religious Studies major any more. I’m a writer who teaches writing and writes about religion. It even says so on the cover of the book. There are several books now that take a more scholarly approach to this topic and they’re all excellent, so if people are looking for that sort of thing, it exists. Why complain that a book that doesn’t promise that kind of approach doesn’t deliver it? This is why I personally try to avoid writing book reviews. There is too much temptation to say “I wish this could have been about what I wanted it to be about.” That’s not a writer’s job. Our job is to write the books we are called to write. If you wish a book were about something else or took a different approach, you can write it yourself.

On the other hand, the book received an award from the Catholic Press Association for “Pastoral Ministry,” which I find hilarious as a person who is overtly critical of the institutional Catholic church at times, and it was also nominated for the best book of the year by the Religion Newswriters Association, which is very high praise considering the caliber of the other nominees. And the reviews in many magazines and newspapers were very accurate about its goals and have started some rich and engaging conversations. You can’t please everyone, nor should we try. I should probably put that on my syllabi.

7) With this book done, what’s up next for you?

Good question. I’m finding myself drawn more and more to the idea of nonfiction writing about religion as justice work and as activism. I’m also interested in writing about religion for secular audiences as well as religious ones thanks to the opportunities I’ve had to contribute to Religion Dispatches, Foreign Policy, and Killing the Buddha on top of my occasional gigs at Catholic magazines like America. I’m working on a book proposal (when I have time!) that loosely has something to do with the spiritual side of justice movements in recent history, but it’s tough out there right now to try to sell any religion related books once you venture out of Christian Corner — which is a lovely place to be, but secular publishers can be skeptical about religion books and religious publishers can be skeptical about reaching a secular audience. But hopefully something will work out and any interested editors are welcome to contact me or my agent, of course. I’m also writing a chapter for an anthology about Thomas Merton, who I’ve long wanted to write more about. And in September I’m off to Rome in September for a weeklong seminar on covering the Catholic church and Pope Francis and very much looking forward to that, and, of course, to the gelato.

Kaya Oakes is the author of four books, including The Nones Are Alright: A New Generation of Seekers, Believers, and Those In Between, and Radical Reinvention: An Unlikely Return to the Catholic Church. She is a senior correspondent at Religion Dispatches and a contributing editor and writer at Killing the Buddha, and her work has also appeared in America, Commonweal, The Guardian, Foreign Policy, and Religion News Service. She teaches nonfiction writing at the University of California, Berkeley and lives in her hometown of Oakland, California.